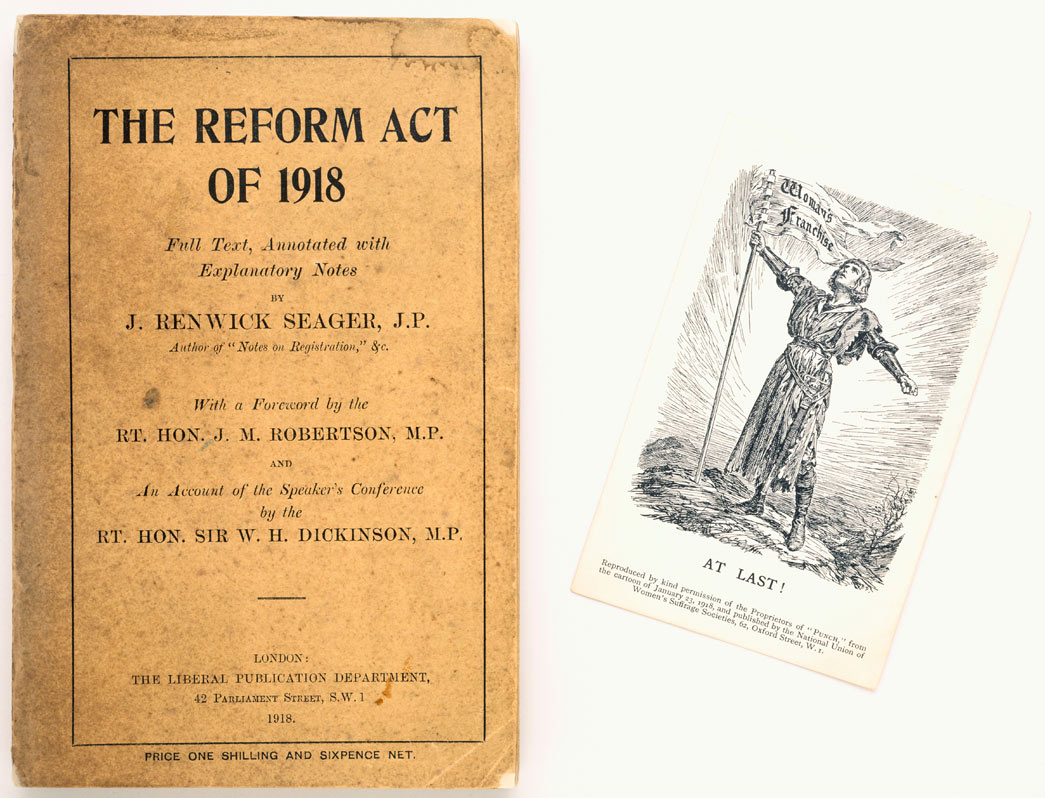

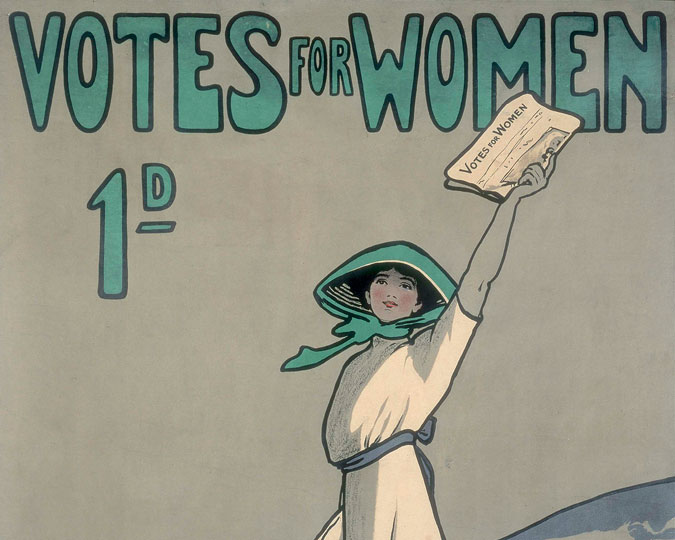

A hundred years ago, after decades of campaigning, women finally won the right to vote in British elections. The December election of 1918 saw 8.5 million women eligible to vote and 17 female candidates stand for election, although only one was elected- and she never went to Parliament.

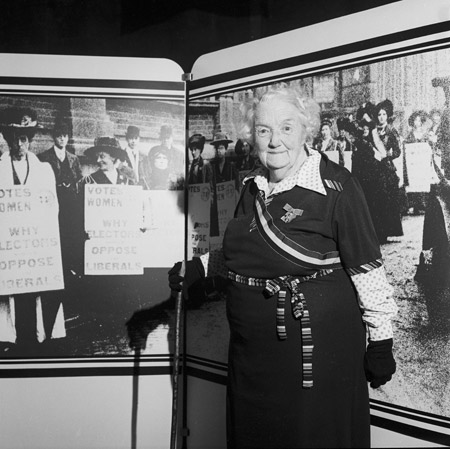

Former suffragette, Connie Lewcock, photographed by Henry Grant, 1978

Connie was attending an exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of women's right to vote. Connie Lewcock OBE, an 84-year-old former suffragette from Newcastle, had helped to set fire to Esh Winning railway station in the name of suffrage.

It was called in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, which had ended just a month before, and it was the first since the passing of the Representation of the People Act, sometimes called the Fourth Reform Act, allowed some women to vote.

Museum of London curator Beverley Cook: "On December 14 1918 women walked shoulder to shoulder with their husbands, brothers, sons and lovers to vote for the first time in a general election. The 100th anniversary provides us with an opportunity to mark a momentous occasion that, at the time, was so overshadowed by the First World War, and the loss of so young men that would have been surely missed on that day."

Women still didn't have equal votes with men...

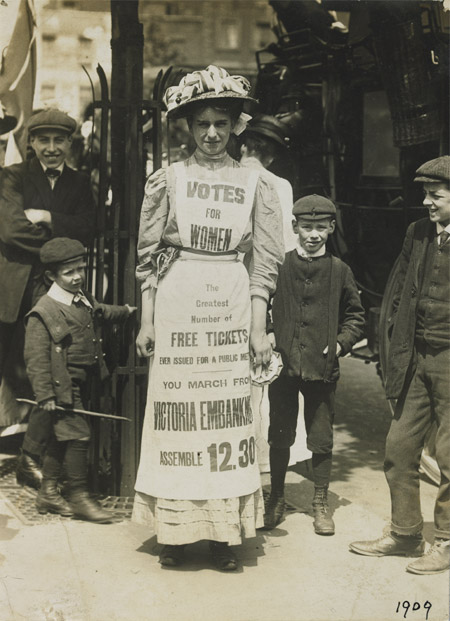

Suffragette Vera Wentworth walking on the Strand, 1909

Aged just 19 at the time, Vera's apron advertised a forthcoming Suffragette march.

Before the First World War, only men who owned a certain amount of property had been able to vote. About 60% of male householders had the vote, but millions of men did not, including many returning soldiers. The Representation of the People Act abolished the property qualification, allowing all classes over the age of 21 to vote- as long as they were male.

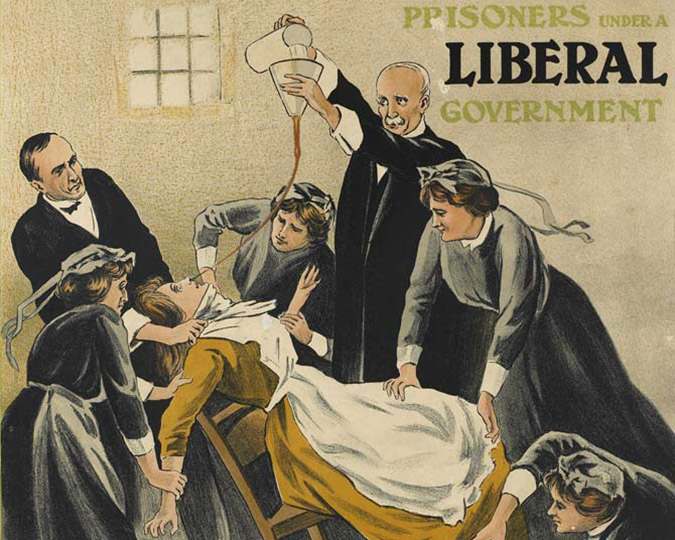

Women were doubly discriminated against: firstly because they still needed to have some wealth to qualify. This was measured by the value of the property they lived in, which had to have an annual rent of at least five pounds. (Equal to perhaps £1000 today. Rent was much, much cheaper in 1918). Secondly, only women over the age of thirty were allowed to vote.

Rather poignantly, many of the 1300 women who served terms of imprisonment, went on hunger-strike and were force-fed for the right to vote were still too young to take part in the democratic process in 1918. Suffragettes like Vera Wentworth, who had campaigned for Votes for Women for a decade, was 28 at the time of this election.

...Because of fears they would out-vote men

The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote to 8.5 million women. This was about 40% of Britain's female population, and women also made up 40% of the electorate (21.4 million people in 1918). Due to the deaths of the First World War, there were over a million more women than men in Britain, and the age limit was introduced to prevent women from being in a political majority. In 1918, government minister Lord Cecil, admitted in Parliament:

"Everybody knows quite well why the age of thirty years was fixed as the age at which women could vote. It had nothing to do with their supposed capacity or incapacity between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one. That limit was adopted in order to meet the objection to the extension of the franchise without some limit of the number of women voters. That is perfectly notorious, and there is no secret about it. That is the reason why the age limit of thirty was introduced, in order to avoid extending the franchise to a very large number of women, for fear they might be in a majority in the electorate of this country. It was for that reason only, and it had nothing to do with their qualifications at all. No one would seriously suggest that a woman of twenty-five is less capable of giving a vote than a woman of thirty-five."

Suffrage campaigners like Milicent Fawcett were disappointed at the continued discrimination, but accepted it as a necessary and temporary compromise to get the vote. Ten years later, in 1928, women were finally given the right to vote on equal terms with men by the Equal Franchise Act.

Nobody knew how women would vote

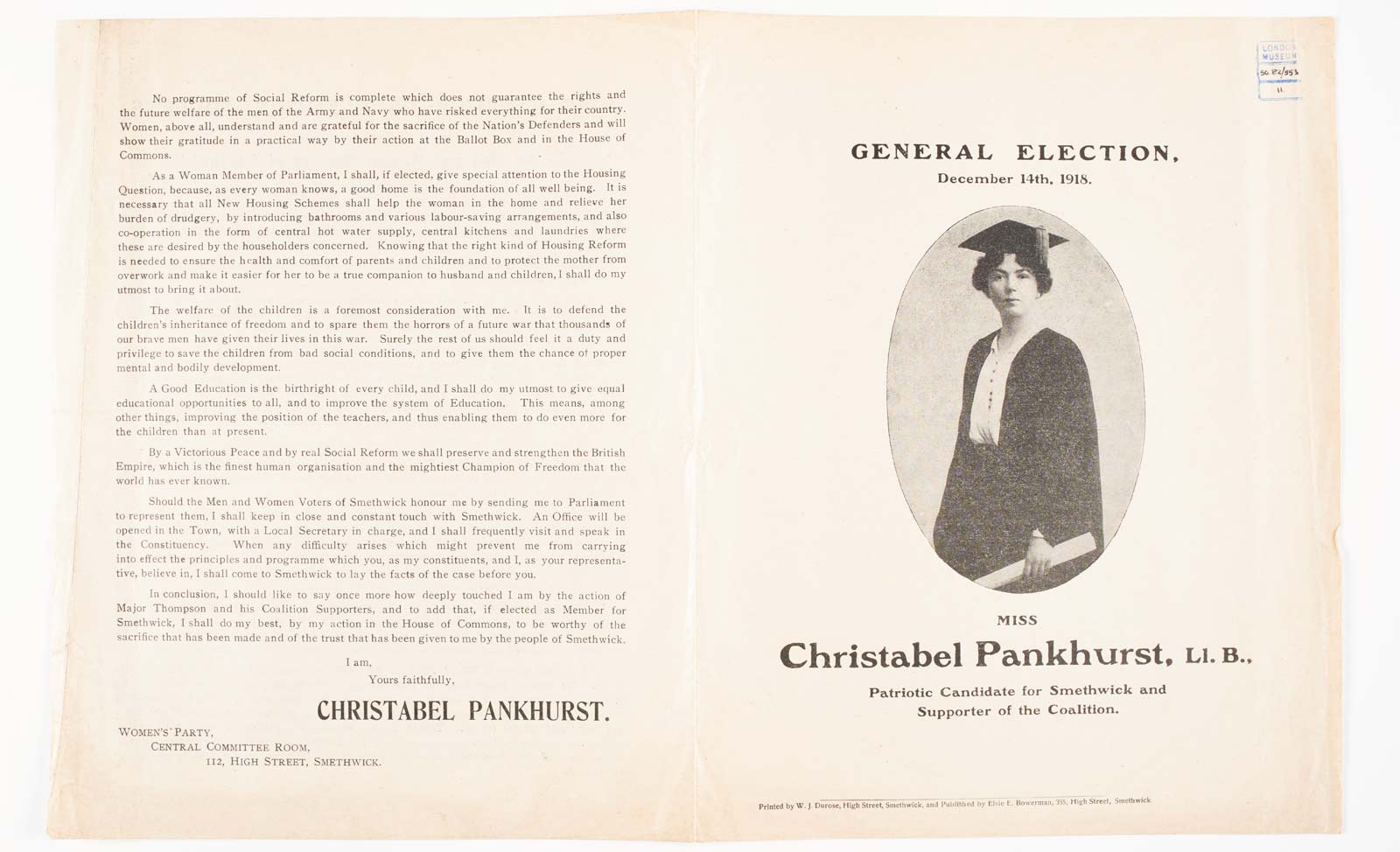

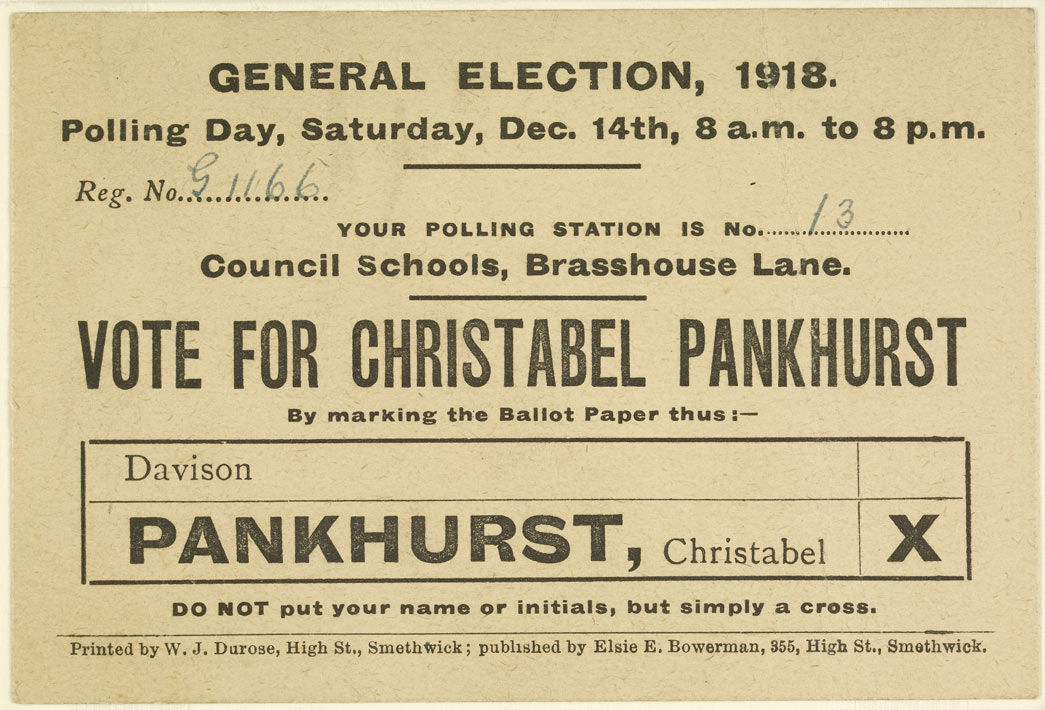

Christabel Pankhurst's election Postcard

iIssued as a campaign flyer for the General Election 1918, Polling Day Saturday December 14 1918.

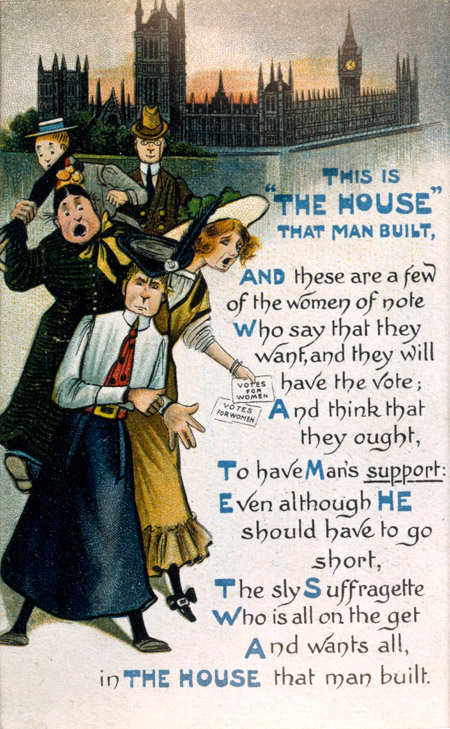

This is the House That Man Built, anti-Suffrage postcard

The postcard depicts Suffragettes as hysterical, unfeminine and, therefore, unworthy of the vote.

Beverley Cook: "There was great interest in if and how women would vote, whether they would know enough about politics to make an informed decision. The day after the election the Sunday Pictorial newspaper made reference to: ‘Mrs Granny Lambert of Edmonton, who is on the voters’ register for the first time. She is 105 years of age, and says she has never heard of Mr Lloyd George. [The Prime Minister]'"

This supposed ignorance by women about political matters was a common theme in anti-Suffrage propaganda. Even supporters were worried about helping new electors: this card urging voters in Smethwick to choose Christabel Pankhurst as their MP shows how to fill out a polling card.

In Chelsea Emily Phipps, running as an independent candidate for Parliament, set up a model polling booth where women electors could practise voting. She also made arrangements to mind mothers' babies while they were absent at the polls.

You could vote for women for the first time

As well as being entitled to vote, women were also entitled to stand as MPs for the first time in 1918. 17 women ran as candidates, from a wide range of political parties including Liberal, Conservative, Labour and the Women's Party. These included senior figures in the Suffragette campaign: Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, and Norah Dacre-Fox from the Women's Social and Political Union and Emily Phipps, Edith How-Martyn and Charlotte Despard of the Women's Freedom League. They were all militant campaigners who aimed to make the transition from lawbreakers to lawmakers.

Beverley Cook: "These women had been empowered by the militant struggle for the vote – they had gained self-confidence through their work as ‘career’ Suffragettes. They were effective organisers and speakers. This self-confidence provided them with the skills, experience and courage to stand as candidates but also support the newly enfranchised female electorate."

Only one woman was elected in 1918, but she never went to Parliament

Constance Markievicz in the uniform of the Irish Citizen Army

Photographic postcard of the Countess Markievicz, the only woman to be elected in the 1918 UK General Election.

Of the women stood for election in 1918, only Constance Markievicz was elected to Parliament, for the constituency of Dublin St. Patrick's, in what was then British Ireland. She was the Sinn Féin candidate, and she's a reminder that the 1918 election was historic for many reasons. It was the first election since the Easter Rising of 1916, which had provoked huge anger in Ireland against the British government, and galvanised the Irish Independence movement. Constance, the Irish-born wife of a Polish count, had herself fought in the Rising and been sentenced to death, but pardoned because of her sex.

At the time of her election, she was in London's Holloway Prison, serving a sentence for interfering with the British government's attempt to conscript Irish men to fight in the First World War. Neither she nor any of the other Sinn Féin Members of Parliament who were elected went to London to serve in the House of Commons. Instead, they created their own Parliament, or Dáil, in Dublin, and declared most of Ireland- which had voted overwhelmingly for Sinn Féin in the 1918 election- to be an independent nation.

When the First Dáil met, and the new representatives counted, Constance was described as "fé ghlas ag Gallaibh": imprisoned by the foreign enemy, meaning the British. It would not be until 1919 that Nancy Astor would be elected as the first woman to serve in the House of Commons.

Not the end of the struggle for female equality

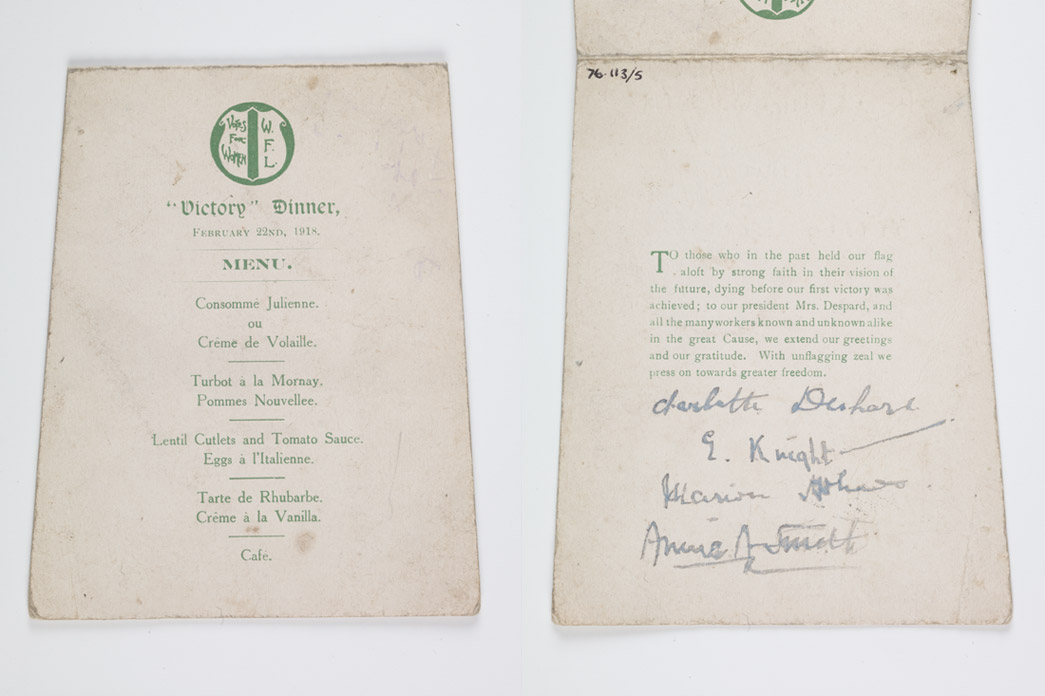

Women's Freedom League Menu, January 3, 1919

Published by the Women's Freedom League on 3 January 1919 to commemorate women candidates who stood for parliament during the General Election of 1918.

Fighting for the vote was only regarded as a starting point for the Suffragettes, who believed that female representation in parliament would lead to legislation to improve the lives of all women and, thereby, facilitate greater gender equality. Disappointed but not disheartened by a series of narrow defeats in the 1918 election, many of these former Suffragettes continued their political struggle. Some moved abroad, to countries such as the United States or Australia, to campaign there for Votes for Women or for access to birth control for women.

This printed menu was for a "Victory" Dinner, organised by the Women's Freedom League on 3 January 1919 to commemorate the women candidates who stood for parliament in 1918. On the reverse is printed the dedication 'to the women candidates of 1918 the pioneers of women representatives in Parliament, we offer our warmest thanks and most cordial congratulations for the plucky fight they put up in the interests of women'. Their fight, for equal rights and equal representation for people of any gender, is one that continues to this day.