Why did Suffragettes march on Parliament on 18 November 1910? What happened to make it Black Friday? And how did this infamous protest change the struggle for Votes for Women?

Why did Suffragettes march on parliament in November 1910?

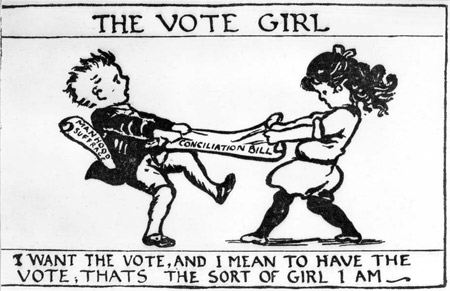

Postcard produced by the Suffrage Atelier, supporting the Conciliation Bill

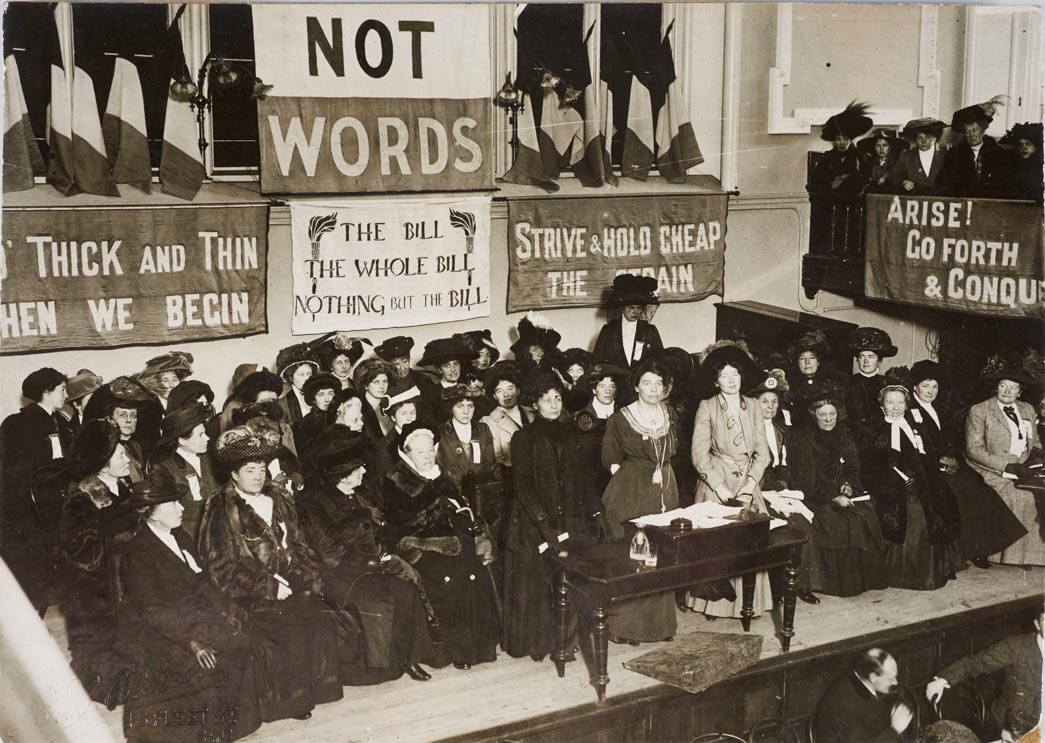

In November 1910, decades of campaigning by both Suffragists and the militant Suffragettes seemed to be on the verge of a breakthrough. The British Parliament was considering legislation that would, for the first time, allow some women to vote. Known as the Conciliation Bill of 1910, it would have given about a million women, mostly wealthy property-owners, the vote. Many votes for women campaigners regarded this as a compromise, but the leaders of the Women's Social and Political Union supported the Bill. In January 1910, leader Emmeline Pankhurst announced they would suspend all militant campaigning - such as window-breaking or assaults on politicians - in anticipation of its passing into law.

The Conciliation Bill had been proposed by a Conciliation Committee made up of MPs from various parties. Although the Liberal Government did not formally oppose the introduction of the Bill it was not regarded as a priority. Prime Minister Asquith, never a supporter of female suffrage, was more concerned about passing his People’s Budget, which proposed higher taxes on the wealthy. In order to force this law through Parliament, Asquith called an election in December 1910, the second within a year, in an attempt to strengthen the Liberal government's majority. A new election wrecked any chance of the Conciliation Bill being considered, and infuriated the Suffragettes who felt so near to partial success.

News that Asquith had called an election reached the Women's Social and Political Union as they gathered in Caxton Hall, Westminster, for their Women's Parliament meeting. Suffragette leaders, especially Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst, felt betrayed by the Prime Minister. There were already plans for a peaceful deputation of the WSPU to the House of Commons, but the three hundred gathered Suffragettes marched on Parliament in a furious mood.

Suffragette Annie Kenney was on the scene: "There was a great storm-burst. All the clouds that had been gathering for weeks suddenly broke, and the downpour was terrific... There was not one of us who would not have gone to our death at that moment, had Christabel so willed it."

What happened to make it Black Friday?

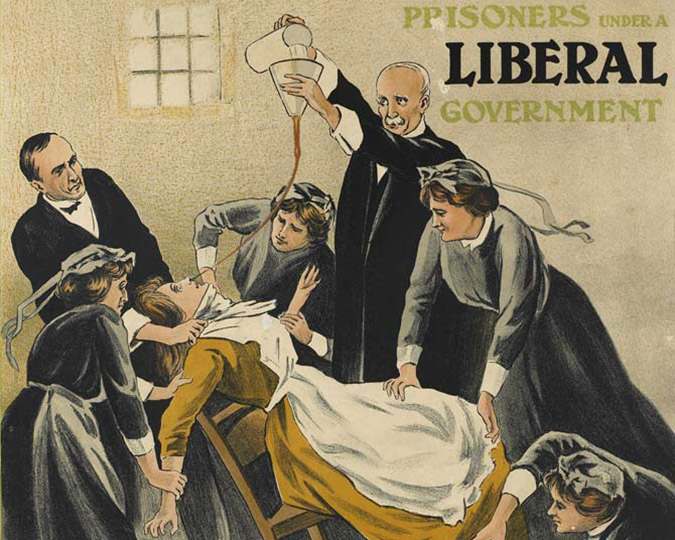

The Women's Social and Political Union protesters were met by a brutal response. After Prime Minister Asquith refused to see a WSPU deputation at 1.20pm, the Suffragettes stayed in Parliament Square and tried to enter the House of Commons. These efforts were met with violent aggression by the police, who beat and hit Suffragettes, and threw them into the hostile crowds for further ill-treatment.

Because of the expected large demonstration by Suffragettes, policemen had been drafted into Westminster from across London, including from rougher areas like Whitechapel. These policemen were unfamiliar with the Suffragette protesters and accustomed to violence. Perhaps even more importantly, the crowds of bystanders on Black Friday were markedly hostile to the Suffragettes.

The scene is captured in this watercolour painting by William Monk, recently uncovered in our stores. In anticipation of the move to our New Museum site, we're currently preparing all of our collections ready for transport to West Smithfield. Hidden in one box we were excited to find this watercolour and pastel drawing of a suffragette demonstration, showing police making arrests outside the Houses of Parliament. On the reverse there was a handwritten note in pencil, which we assume to be by the artist William Monk. It reads: ‘Suffragettes, sketched from actual scene’.

Suffragette Struggling with a Policeman on Black Friday 1910

Photograph from Barratt's Photo Press Ltd.

One of the most shocking elements of Black Friday was the repeated sexual assaults of female protesters. One Suffragette noted: "Several times constables and plain-clothes men who were in the crowds passed their arms round me from the back and clutched hold of my breasts in as public a manner as possible, and men in the crowd followed their example... My skirt was lifted up as high as possible, and the constable attempted to lift me off the ground by raising his knee. This he could not do, so he threw me into the crowd and incited the men to treat me as they wished".

Many Suffragettes claimed there were plain-clothes policemen hidden in the crowds who were inciting and committing some of these brutal assaults.

The Suffragette, May Billinghurst campaigning in her wheelchair

One of the protesters was May Billinghurst, a disabled Suffragette who used a wheelchair due to infantile paralysis. She described her treatment by the police on Black Friday:

"At first, the police threw me out of the machine [wheelchair] on to the ground in a very brutal manner. Secondly, when on the machine again, they tried to push me along with my arms twisted behind me in a very painful position, with one of my fingers bent right back, which caused me great agony."

Thirdly, they took me down a side road and left me in the middle of a hooligan crowd, first taking all the valves out of the wheels and pocketing them, so that I could not move the machine, and left me to the crowd of roughs, who, luckily, proved my friends."

Suffragette Ada Wright, on the cover of The Daily Mirror November 19 1910

Wright was one of the Suffragettes knocked to the ground by police on Black Friday 1910.

Suffragette Ada Wright, fifty years old at the time, was featured on the front page of the Daily Mirror on 19 November 1910. She had been struck by a policeman as she tried to enter the House of Commons. The sexual assaults went unremarked upon by the Edwardian press. Although in general journalists described the Suffragettes unsympathetically, blaming them for inciting the violence, the Daily Mirror did note that the police seemed to enjoy the fighting. Home Secretary Winston Churchill was blamed for encouraging the police in their violent response. 119 protesters were arrested, but all were released without charge the next day, on Churchill's orders.

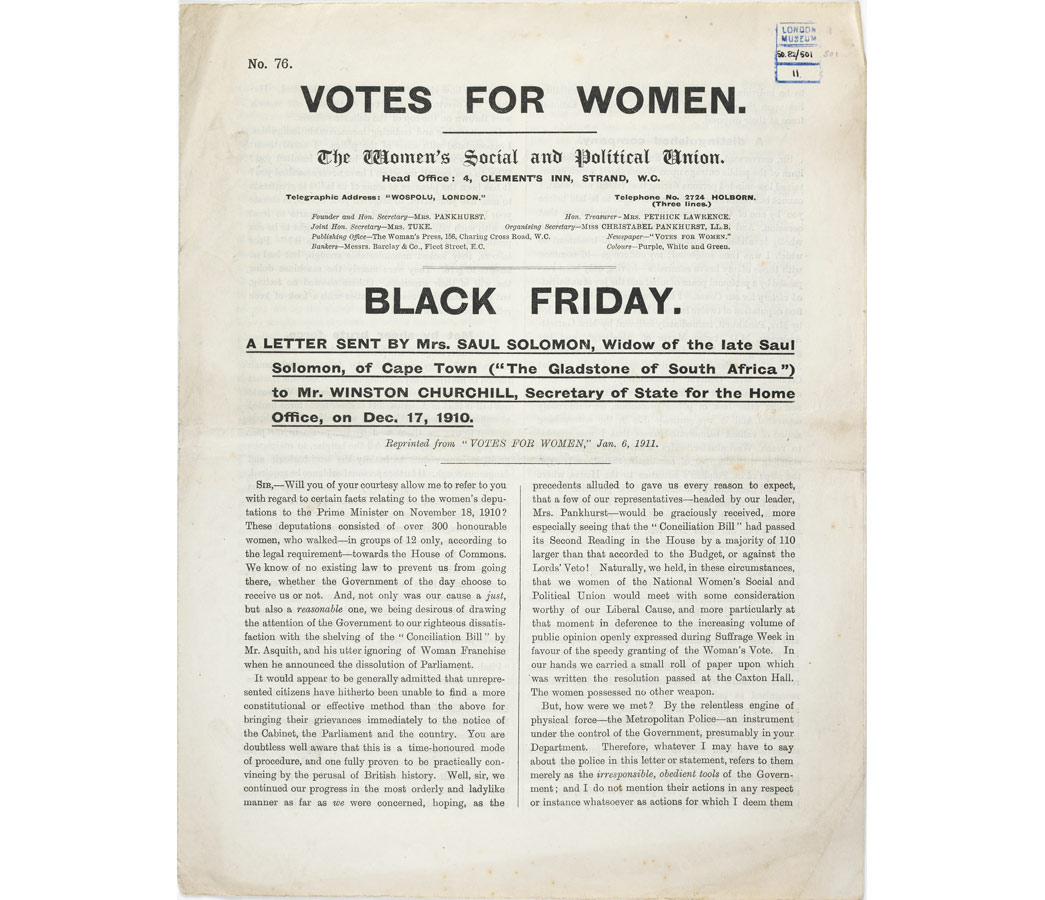

Leaflet No. 76, published by the Women's Social and Political Union. Entitled 'Black Friday'

The leaflet provides a detailed account of the ill-treatment of women during a deputation to the Prime Minister on 18 November 1910.

It's impossible to know exactly what happened during the Black Friday protests of 1910, because all accounts differ so markedly. The police, observing journalists, and Suffragettes all tell different stories about the levels of violence and who caused it, and all had different reasons to twist their stories: the police to excuse themselves, tabloid journalists to excite their largely anti-Suffragette readers, and demonstrators to inflame passion for the Votes for Women cause. However, the many personal accounts, photographic and physical evidence make it clear this was a day of violence. The Suffragette base at Caxton Hall was turned into a makeshift hospital for Suffragettes with black eyes, sprained joints, and bleeding noses. Suffragette propaganda immediately proclaimed this event as 'Black Friday', the darkest day of the campaign to date.

How Black Friday changed the Suffragette struggle

The violence of the police response on Black Friday changed the tactics used by the Women's Social and Political Union and other supporters of Votes for Women, for two important reasons.

Firstly, many WSPU campaigners were not willing to continue risking violence and sexual assault. Large deputations were no longer considered safe and, instead, suffragettes 'went underground' to wage guerilla warfare against the government in their struggle to win the vote.

But there was a second key change after November 1910: many Suffragettes were emboldened by their experiences. They felt betrayed by the Liberal government, which had seemed to promise the Conciliation Bill and encouraged the WSPU to suspend militant campaigning. After Black Friday, many Suffragettes were ready to meet state violence with extreme militancy.

In November 1911 window-smashing was officially adopted as a key campaign tactic by the Women's Social and Political Union. Other destruction of property, like attacks on public artworks, and arson, were also embraced. The Suffragette newspaper reported over 300 incidents of arson and bombing between 1913 and 1914.

Many of the Suffragettes now attended demonstrations armed with coshes, whips, and toffee-hammers, for window-smashing and protection. A small group of WSPU militants formed a bodyguard for Emmeline Pankhurst; all were trained in jujitsu and carried Indian Clubs to protect the Suffragette leader.

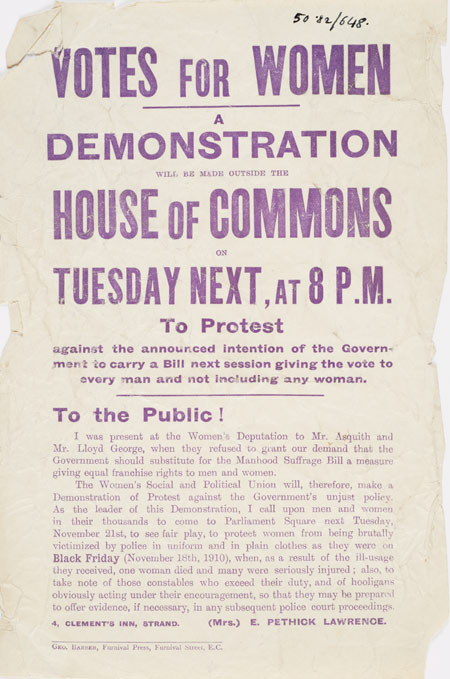

Votes for Women, A Demonstration, outside The House of Commons, 1911

Handbill issued by the Women's Social and Political Union announcing a demonstration to be held outside the House of Commons on Tuesday 21st November 1911.

Suffragette mass protests did not end with Black Friday: this handbill calls for demonstration against the Government's intention, in 1911, to introduce a franchise bill that would give the vote to all men but continue to exclude women.

Organiser Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence who calls upon 'men and women in their thousands' to come to Parliament Square to protect the demonstrators from being brutally victimised by the Police, as they had been the year before on Black Friday.

Despite Pethick-Lawrence's hope that the demonstration would be peaceful, increased frustration amongst the Suffragettes resulted in the mass-smashing of windows and a confrontation with the police that led to the arrest of 220 women, over 100 of whom were charged with malicious destruction of property.

Between 1910 and 1912, three Conciliation Bills giving limited female suffrage were drafted and debated by parliament. None succeeded in being passed into law. It was not until the Representation of the People Act of 1918 that some women over the age of 30 finally won the right to vote in British parliamentary elections. By then, militancy had been suspended for four years, after Emmeline Pankhurst encouraged her supporters to focus on the war effort - working with the government to encourage women to undertake war work. But the crusading Suffragettes, who had been outraged and inspired by Black Friday, had finally partially achieved their goal of Votes for Women, although ironically many who experienced such brutality that day in November 1910 were too young to vote in the general election of December 1918.