In 2016, the Museum of London conducted a major review of our vast Working and Social History collections. For two years, we worked inside the museum's archive at Hackney, re-evaluating the many objects we are currently unable to display in the museum. Beverley Cook picks a few fascinating objects that she learned more about during the review, each of which reveals more about the working history of the city.

Wooden shoe lasts used by the ballet-shoe maker Colombano Porselli

One of the most important functions of the museum is one that most of our visitors will never see. The majority of our collections are held in storage, and we can only put a tiny fraction on display in the museum itself. As well as being a resource for researchers, the objects in our stores preserve a record of those parts of London's history that have now vanished. That's especially true of the working history collections, which represent all the key skilled trades for which London is famous. These wooden shoe lasts were used by Colombano Porselli to create beautiful hand-made ballet shoes. Many of the lasts were individually crafted to the exact shape of the feet of the world’s greatest ballet dancers, to ensure the shoes were a perfect fit.

Within our wonderful costume collections we also have some finished ballet shoes made by Porselli, who came to to London from Milan in the 1920s. The ballet shoes are beautiful, of course, but for me it is the processes and skill involved in making the shoes that is of greater interest. It was such a pleasure to handle Porselli’s hand tools, lasts and workshop materials during our collections review- particularly because I remember visiting the Porselli shop near Cambridge Circus as a child, to get my ballet shoes! These objects have such a personal connection to their owner- it's easy to imagine him using them in his cramped tiny workshop. I'm so glad the museum had the opportunity to collect these items when Porselli's closed in the 1980s and preserve one small fragment of London's working heritage.

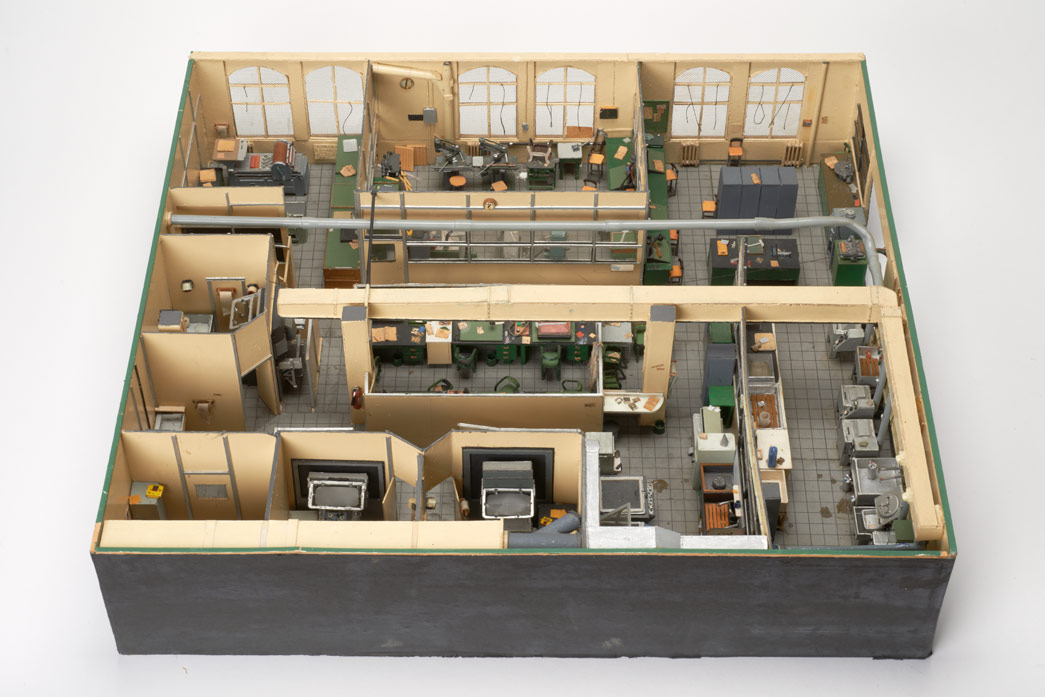

Model of the Evening Standard's Fleet Street office, 1977

We have quite a large number of models in our collection, but those that aren't on display spend much of their times boxed up in crates, to protect them from damage and the environment. The review provided the opportunity to open all the crates and assess and appreciate our wonderful model collection in its entirety.

This model shows the Process Engraving department of the 1977 Evening Standard office, which prepared the presses to print the newspaper. We believe that the person who made this model- who also donated it to the museum- worked at the Evening Standard when it was still based on Fleet Street. It seems likely, therefore, that he may have used materials from around the office to construct it- metal components, for example, might be made of offcuts from the engraving process.

Fleet Street was once synonymous with London journalism, with newspapers written, edited and printed right in the heart of the city. The traditional heart of British journalism began to decline with the introduction of massive printing presses that required larger, purpose built premises. Whilst the national newspapers moved out of Fleet Street provincial newspapers still retained offices in the area. In fact, the last two journalist still working on Fleet Street left the week after we put this model on display, when the Dundee Sunday Post closed its London office. This model is a wonderful snapshot of a vanished world, a traditional London industry with a unique culture that employed generations of Londoners.

Hand-cranked ice cream maker, 1911, & ice cream molds, c. 1910

This hand-cranked machine dates from 1911, but it has a surprisingly modern purpose- it's an ice-cream maker, used to blend ice, milk and flavourings in a household kitchen. The silver moulds were used to press the ice-cream into decorative shapes, perhaps to entertain at dinner-parties. I love the machine not just because it's amusing to find a domestic ice-cream maker in an Edwardian kitchen, but because it demonstrates how we continually discover new things about our collections. When we uncovered this machine, we weren't certain of its origins. Our original research, starting from the maker's label, for "Frozo Specialties", identified the unusual object. I like to imagine it would have been used in the kitchens of London’s aspiring middle classes. Families who may have had one or two domestic servants but wished to recreate the luxurious lives of the Edwardian elite.

Fittings from Holloway Prison, 1903-1971

Surveillance photograph of suffragette prisoners; 1913

Taken by an undercover photographer in the yard of Holloway Prison; ID no. 50.82/1485

Suffragette hunger strike medal

Presented to Emmeline Pankhurst after her incarceration in Holloway Prison in 1912; ID no. Z6033/1

Holloway prison, in north London, was a woman's-only prison

from 1903, and it's where many prominent suffragettes were imprisoned during

the campaign for votes for women. In 1971, the prison was rebuilt, and several of

the original Victorian gaol fittings were donated to the Museum of London. Our

store now holds a cell door, barred window and railings that imprisoned

thousands of Londoners, including over 300 Suffragettes. Many of these women staged hunger-strikes

whilst in prison, and this hunger-strike medal was given to Emmeline Pankhurst,

the Suffragette leader, after she endured a term of imprisonment in Holloway for "conspiracy

to incite persons to commit damage to property".

I've studied the suffragettes for years, and the museum displays a wide selection of material, from campaign banners to hunger strike medals. However, it's one thing to have an intellectual understanding of the imprisonment suffered by these women, and another to actually see the prison bars of their cells. It offers a visceral connection to their lived experience, and also shows the sometimes suprising connections between different parts of the museum's collection.