What stories can hair tell us? The recently opened Talking Point gallery asks visitors that question. We ask the creators of the display what their hair says about them.

A prevailing childhood memory of mine is of my mother cutting my hair. We were living in a flat in Isleworth, I would have been around four or five years old. I had recently started school, having recently moved to the UK, and my grasp on English was well behind that of my peers. She cut my hair into a perfectly reasonable, if not quite perfect, bob. When I saw myself in the mirror, I cried. My complaint? ‘I look like a pumpkin!’

This is one of my first memories of London, and indeed, of my life. A topic that might be wrongly dismissed as shallow or trivial, our hair (or lack thereof) often relates strongly to our perceptions of ourselves, our image and our identity. That is why I believe that hair can be a neat segue into storytelling, about ourselves and society at the time.

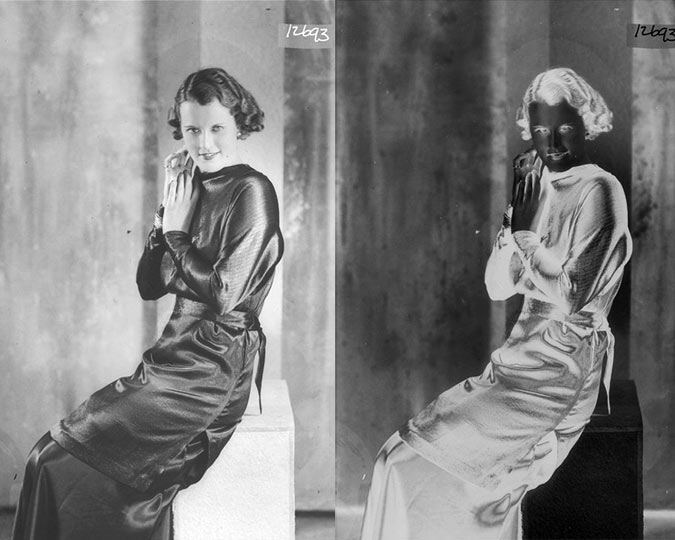

Ladies in the most Fashionable Head Dress, 1791

Caption for the plate ID no. 2002.139/872, “Printed for fran. Power & Co. No 65 St Pauls Church Yard. Ladies in the most fashionable head dress.”

The Museum’s recently opened Talking Point gallery uses hair as the means for starting a conversation about the lives and identities of Londoners. In three rooms, the installation uses objects, sound and vision to explore the significance of hair across millennia. It is human to care about the image that one projects, and hair can be critical to this image.

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why time, money and endurance can go into a hairstyle. A comb could represent the pain of detangling knots or it could be a cherished ornament. The variety of combs available is testament to the variety of hair textures.

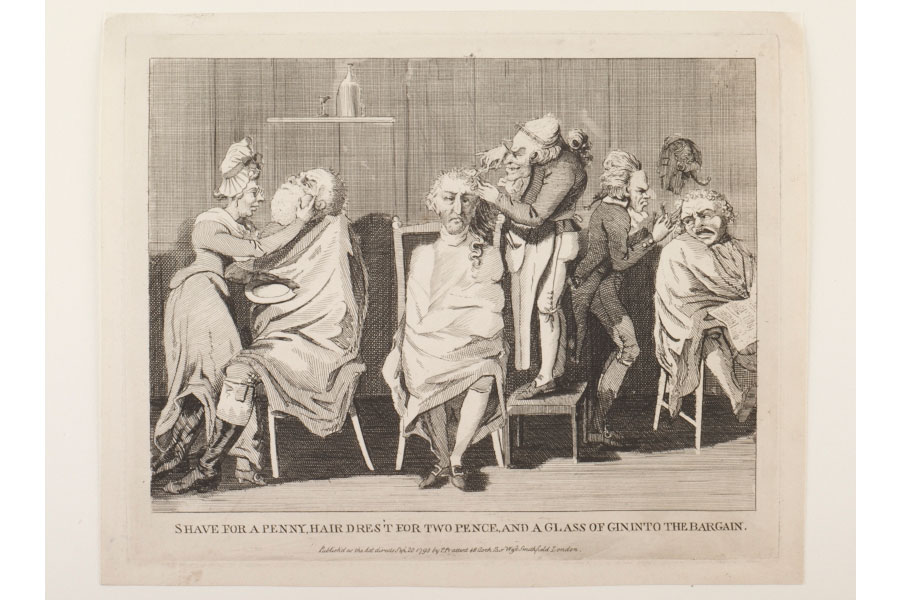

A barber shop can become a gathering ground, a visit to it could be a social occasion or an act of self-care. They may signify the presence of a community and the frequency and profile of their visitors can be revealing of wealth and changing attitudes to grooming.

A wig can become iconic to someone’s place in history. The wearing of a wig does not necessarily mean an absence of hair, it can be a stylistic choice or the demonstration of a cultural or religious tradition, as with some orthodox Jewish communities.

Engraving of barber shop by Isaac Robert Cruikshank, 1793

Engraving, 1793, by Isaac Robert Cruikshank, ID no. 49.10/13, captioned 'Shave for a penny, hair dres't for two pence, and a glass of gin into the bargain'

The creators of the display are no exception – they each tell a story about their hair.

Francis Grew, Senior Curator of Archaeology

“I remember going to a barber in Moorgate, it was just before a smart event. I spent £20 in that place – double what I usually would. He asked me "what do you want?" and I said “well, make it look respectable”. His response was to say “sorry, but I could never make a gentleman of you!” He wasn’t joking. It was made quite clear to me he felt that I shouldn’t be in that shop.”

Felicity Paynter, Senior Content Developer

“I've never had a great time with fringes. I spent many months in headbands as an 11-year-old trying to grow out the thick curtain to my forehead. At 26, the fringe returned when I told my hairdresser he could 'do anything'. I left with an asymmetric do and an inch-long, demi-fringe that spiked up like a cockatoo when I slept. Luckily I met my partner that year and he looked past the tiny fringe. And the return of the headbands.”

These days, I’m less reminiscent of a gourd, but my hair remains imbued with memories. How about you?

Join us at the Talking Point gallery at the Museum of London for a good hair day.