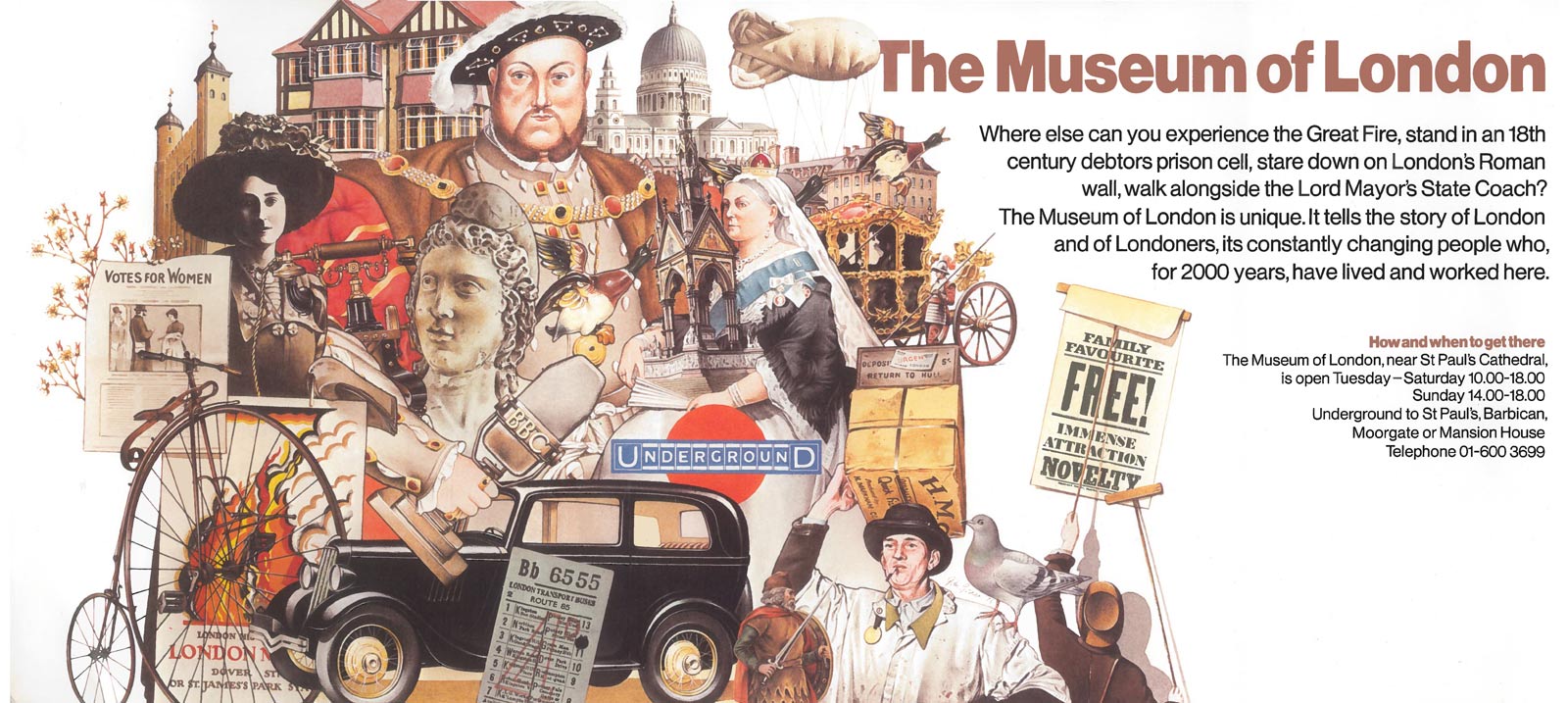

As we head towards the 46th anniversary of the Museum of London's opening, by Queen Elizabeth II in December 1976, two of the museum's longest serving staff recall the challenges and triumphs of creating a brand new museum- just as the Museum of London makes plans to move to a new home in Smithfield.

At 46 years old, the Museum of London is one of the youngest of Britain's major museums. It was created in 1976 by merging the collections and staff of two pre-existing organisations: the London Museum, founded in 1912, and the Guildhall Museum, founded in 1826. The London Museum, funded by the British government, and the Guildhall Museum, by the Corporation of the City of London, had not always seen eye-to-eye. Their very similar goals- to collect and house the "treasures of London's past"- sometimes led to mutual suspicion, and some important archaeological discoveries, like the Cheapside Hoard, had to be split between the two museums. However, by 1960 the decision was made to join the two into a single "Museum of London", to be housed in a new building near St. Paul's Cathedral. 16 years later, the museum finally opened on the edge of the Barbican complex, in a building designed by the architects Powell & Moya.

We spoke to Cliff Thomas, Museum of London Chief Technician, and John Clark, Curator Emeritus and former Senior Curator of the medieval collections, about what it was like to work through the sometimes tumultuous birth of a new museum.

Cliff Thomas: I went straight from school to the London Museum, starting as an apprentice technician. It was 1973 and I was just 17. In those days we were based in Kensington Palace, mostly in the lower floors. We didn't have anything like the facilities we do now- no lifts and no large machinery. We technicians used to do a certain amount of restoration work, which would be handled by the professional conservators now.

John Clark: I joined the Guildhall Museum in the autumn of 1967, after two years at the Wisbech Museum at Cambridge. I was the assistant curator. When I started, the Guildhall Museum was based in the Royal Exchange, and then we moved to offices on the high walk [just along the road from the current Museum of London site].

The plans to move to the London Wall site were already in place then, but the application to buy and demolish Ironmonger’s Hall [which stands in the centre of the Museum of London site] were refused, so that threw a spanner in the works. The architects had to go back to the drawing board. That was when curators from the two museums started to come together to talk about integrating our collections and our galleries.

John Clark: I was seconded across to the London Museum in 1972, to help out on an exhibition called Chaucer’s London. That was the first time curators from both museums had worked together correctly. It was quite a different atmosphere- the London Museum was much bigger, a national museum, and had far more staff and resources. We had one secretary at the Guildhall Museum, and if you wanted to get some photocopying done you had to take it down the road into the Guildhall and queue for the one photocopier.

Kensington Palace, 1819

Etching and aquatint. ID no. A7019

Back then, the London Museum was based in Kensington Palace- what was that like?

Cliff Thomas: It was a completely different environment- the museum was set back in the middle of a park, and backed on to what we used to call Millionaire’s Row- it’s got lots of embassies on it now.

The technician’s workshop at the London Museum looked out over the quadrangle in Kensington Palace- we’d quite regularly see royalty walking around. I remember seeing Princess Margaret fairly often. There were no loading bays like we have at the museum now, just quite narrow passageways. When we had an unusually large object, we had to request permission to drive into the palace yard, and take it into our workshop through the window.

John Clark: It made me feel rather like an interloper there- because it was in a royal palace, and you only had to go through a locked door before you were in the State Apartments. There were all these grace and favour homes for minor royals and the like, and the museum was rather confined to the basement. The main entrance was through Kensington Gardens, which were closed and locked up after dark, of course. If I was working late, and wanted to get to the tube station at Queensway, I could walk through the park in the dark and climb over the railings by the park gate.

Head of Mithras, AD 180-220

Part of the collection discovered in the Walbrook Mithraeum in 1954 & reunited in 1976. ID no. 20005

Did that difference in size between the London and Guildhall Museums cause any friction? Were the Guildhall Museum worried about being swallowed up by its bigger partner?

John Clark: Not really, because the Guildhall’s collection was so strong we always felt that we were pulling our weight. It was wonderful to bring together some objects that had been scattered across London’s museums. The sculptures from the Temple of Mithras, for example, and the Cheapside Hoard, had been separated between the Guildhall Museum and the London Museum when they were discovered. Now they’re united again.

And the two museums had different strengths. Everyone at the Guildhall Museum was an archaeologist by training and inclination, and we specialised in the Roman and early history of London, whereas there were specialists in more modern periods at the London Museum. So it was quite easy to sit down and sort out who would be in charge of what. I was to be assistant to Brian Spencer, who was in charge of the medieval collection at the London Museum, and had organised the ‘Chaucer’s London’ exhibition.

Cliff Thomas: We had regular get-togethers with the staff from the Guildhall Museum, and I don't recall any tensions between us. With the technicians, our attitude was always just to get on with things. The impact of the huge move just swamped everything.

H.M. The Queen on Thursday 2nd December 1976 opening the Museum of London

Also present Colin Sorensen, keeper of the Modern Department & Tom Hume, Director of the Museum of London.

Did the move to the

London wall site go smoothly?

Cliff Thomas: We technicians were some of the first to head out to the new site, a year in advance, working in the basement alongside the conservators. We were preparing the displays, working very long days- I think I worked on average from 8.30 in the morning to 11 at night, and weekends as we approached the opening deadline. My overtime paid for the deposit on my house!

John Clark: We closed both existing museums by 1975 to prepare to move

the collections into their new galleries, but the new building wasn’t ready

yet- it was just a concrete shell.

Were the galleries

all ready in time for the grand opening?

John Clark: Not quite. I remember escorting the Queen around the medieval gallery and noticing that there were still two strips of masking tape on the wall, showing where some paintings were going to be hung- I didn’t point it out to her.

Cliff Thomas: We opened on time. We might not have been ready according to the designers' plans, some of the displays that were supposed to be there weren't, but the public didn't know that. We all got presented to the Queen when she visited to open the museum.

The Museum of London's first public visitor, 1976

Blanche Hammond was presented with a model London Bus by Director Tom Hume.

John Clark: There was another issue, which was that there was still ongoing archaeological research across London while we were designing the galleries. We commissioned a large model of the Tower of London to be the centrepiece of the new medieval gallery. It was very expensive- I always said it cost more than William the Conqueror paid for the White Tower to be built, in terms of face value! I gave the model-maker all the latest research, but while he was building it, fresh excavations proved that some of the details were already wrong. Fortunately, we were able to fudge some changes.

I’m sure you’ve seen some dramatic changes to the museum during the last forty years?

Cliff Thomas: Certainly some big ones, like the opening of the Museum of London Docklands. That presented some interesting challenges to my team- it was the first time we had ever hung river vessels in the galleries, that sort of thing.

We’re a lot more conscientious about health and safety. During the last forty years I’ve done things you’d never get away with now. We were once collecting some objects from Alexandra Palace- there was an old theatre there that had been used as prop storage by the BBC, so there was a Tardis sitting on stage. We needed to go up into the flies, in the wings of the stage, to collect the equipment. The caretaker told us: “Be careful up there, because half of the boards are rotten. You’ll fall through the platforms, thirty feet down onto the stage, then you’ll probably go through that and fall sixty feet into the space under the theatre.” Needless to say, we do things very differently now.

John Clark: One thing that really stands out is how the staff has changed. When the Museum of London opened, there were three specialist curatorial staff looking after the medieval collections- by the time I retired, there was just me. I feel sad at the loss of expertise. But the responsibilty has been spread across the museum. For example, curators were responsible for maintaining all the records of the collections, organising loans and so on (and if the loan was to a museum abroad, that involved plenty of paperwork!). Nowadays there’s a registrar’s department to make sure it’s all done properly.

What advice would you give for planning the Museum of London’s next move, to the Smithfield General Market site?

John Clark: Forty years ago everything was new – none of us had ever been involved in such a large project before. There’s been plenty of experience since – and perhaps the present staff can learn from our mistakes!

Cliff Thomas: Because of my work, I look at things from a practical point of view. Moving a whole museum is a huge amount of work, but I know everyone at the museum is prepared for that. There will always be logistical problems, but nothing we don't have the expertise to overcome. Technically speaking, moving the Museum of London to a new site should be easier than joining two established museums together, as we had to do in 1976.