As part the yearlong Punk.London celebration, we opened a Show Space display, Being Punk. The display was designed by Fashion History and Theory students from Central Saint Martins, working with Beatrice Behlen, the museum’s senior curator of fashion and decorative arts, and Jen Kavanagh, curator for Punk.London. Here Beatrice talks about what Being Punk means and how the students created the exhibit.

What inspired you to bring in the Saint Martins’ students to work on Being Punk?

We regularly use our Show Space area to put on smaller, more experimental displays, often connected to current relevant topics. When the punk project came up, we thought it was a perfect opportunity. I knew these students from teaching, and I thought it would be great, partly to demonstrate the relevance of punk to a younger generation, but mainly to get their input. Having young students interviewing people who were – or still are - punks, giving their own, unique take on the fashion and the movement, it felt appropriate for the subject.

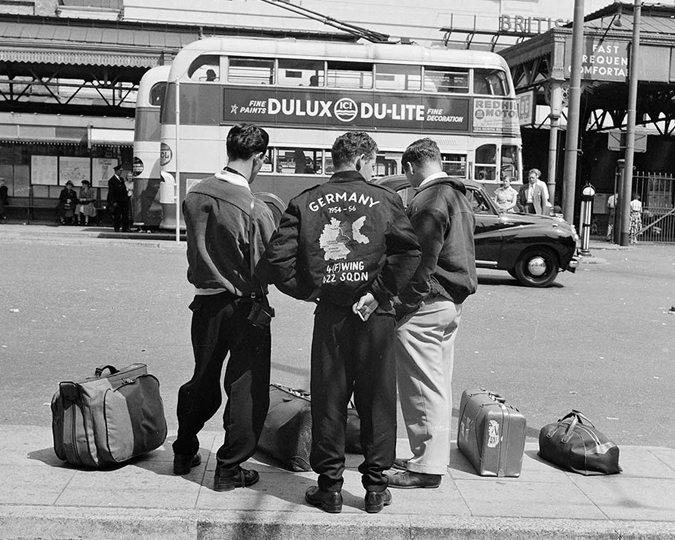

The students came up with the idea of “becoming a punk”, trying to capture the process that people went through to dress up and live a punk lifestyle. So they’ve designed three display cases. The first is a typical 1970’s teenager’s bedroom, with a punk outfit ready to put on. Then there’s a display using a large photograph of punks on the streets of London, taken by Henry Grant. Finally, the last case represents a nightclub, where someone is about to listen to a band. It’s sort of a day in the life of an imaginary punk girl.

Sophie the punk

Wearing Life Guards tunic and leopard skin trousers. ID no. 80.531/5

Punk is of course not just about the clothes you wear, but also the attitude, the lifestyle, the ethos. If the project has taught me anything, it is that there’s not just one “punk”, although there are some constants. For everyone it started with the music but for some the main thing was fashion, being able to break the rules of what was generally accepted, for others, it was the politics. In the conversations we had with punks, we had many people saying that it changed their life.

How is that reflected in the display the students designed?

It’s more experimental than what we normally might have done. They’ve taken outfits donated by real people, and elements from photographs and oral histories, and combined them into a sort of composite story. So the first outfit actually belonged to Sophie, a 14-year-old female punk, but the bedroom set- although it uses real 70’s wallpaper- is mainly an imaginary scene.

Zena's dress

Red & black 'Anarchist' dress, purchased at Swankey Modes, Camden Road. ID no. 2012.15/1

The same with the last case. The students have taken clothes from a real person, named Zena, and shown them in the toilet cubicle of a nightclub. It’s a snapshot of someone changing out of jeans and a T-shirt and into a dress and high heeled boots, in a toilet stall that could be from somewhere like the Roxy in Covent Garden. The students seemed to have a good time scrawling graffiti on the walls!

So do you think

they’ve captured the spirit of the punk subculture in these displays?

Well, they’ve shown one version of it. We also have excerpts from two oral histories and a film so visitors can find out more from punks themselves. Really, these objects can only catch one person’s story, but I think this display does a good job of representing a wider range of people’s experiences. A lot of punk history focuses on a few exceptional individuals – it always seems to be the Sex Pistols or Vivienne Westwood. But most people could never have afforded to shop at SEX or Seditionaries on the King’s Road. They found or made their own outfits. We’ve tried to capture a little bit of that DIY spirit.

Zena in her favourite T-shirt

Photographed late 1970s/early 1980s. Private collection, used with permission.

There have been some

criticisms of the Punk London project. We even had a small group of (very nice)

protestors at the first punk event we did at the museum this year. Do you think

it’s “un-punk” to put a display in a museum?

No, I don’t. That suggests that what you see in cases in museums is dead, consigned to the past, but I think that the opposite is true. What you see on display is now preserved as part of our shared history. What’s the alternative? Letting these things decay in an attic or be thrown away? What we choose to put in museums shows what we value as a society.

I like that the Show

Space display is just around the corner from the Lord Mayor of London’s state

coach. We’re demonstrating that punk is another cultural treasure of the city,

worthy of preservation.

Yes. We have changed the way we display some of the punk items, though. I don’t like to display punk clothes on mannequins, as we do with much of our dress collections. It seems too much like a shop, which doesn’t gel with punk. I’m really pleased that the students came up with a solution, which is to display the clothes as though someone is just about to get dressed in them.

That also reminds us that punk was different things to different people – for some, it was a temporary look, something to do on the weekends. But even that was challenging- you’re talking about a fashion revolution. Some of the punks we talked to mentioned being shouted at on the street – or worse. Another was talking about how when she dressed in her punk clothes, her mother would refuse to acknowledge her on the street.

Does punk still matter today?

To me, punk really changed things. Being a fashion curator I’m particularly interested in that aspect. You had subcultures with their own styles before punk, of course. There were the teddy boys and the mods. But punk was less regimented, there was more choice, particularly for women. There was never a strong teddy girl look, but female punks dressed as provocatively as the men. Wearing deliberately dishevelled or ripped clothes- that wasn’t really done before, unless of course you were poor.

The female punk I mentioned earlier, the one whose mother ignored her, told us something else. During the week, she worked for the gas board, and she put on what she called her “old woman’s suits”, that she had bought second-hand. That, for her, was the dressing up, her punk outfit reflected who she really was. I think a lot of people felt like that, for the first time they could express who they really were.

Punk.London was a year of events, gigs, films, talks, exhibits and more celebrating 40 years of punk heritage and influence in London.