22 June 2018 marked the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the ship Empire Windrush at Tilbury Dock, Essex, the beginning of a new chapter in the story of London. The 802 Caribbean citizens onboard were the first of 500,000 Commonwealth citizens who settled in Britain between 1948 and 1971. They were invited to live as British citizens and help rebuild the "mother country", but many faced prejudice and unequal treatment that continues until today.

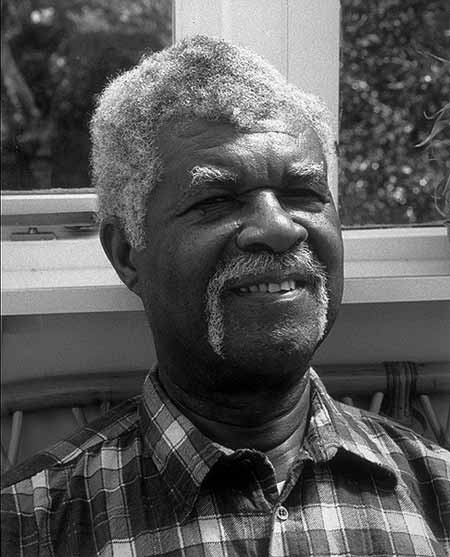

Sam King, Windrush passenger: "They were trying to find a way in Parliament to stop us, but legally they could not."

So

how long did the journey take that time?

Sam King: Three weeks. We left on the 24th of May, which was Empire Day, and arrived in Tilbury on the 22nd of June. Now, the reason why we took so long, after a while out of Jamaica officially the boat developed engine trouble and we had to go in to Bermuda for three days. We don’t believe in English. I being born in the Colonies, if the English man told me something I am not going to accept it I’m not bright, but I’m not stupid. History told me that. We felt, and the newspaper anyway said it, that they didn’t want us. And they were trying to find a way in Parliament to stop us, but legally they could not. So we stayed about two and a half days in Bermuda. So we left on the 24th in May and arrived the 22nd of June.

Sam King, 1999

King (1926-2016) was an RAF serviceman, one of the founders of the Notting Hill Carnival, and the first black Mayor of Southwark.

That's the voice of Windrush passenger Sam Beaver King, recorded in an oral history for the Museum of London in 1999. King was one of the 802 Caribbeans who immigrated aboard the Empire Windrush, the first major influx of Afro-Caribbean people to come to Britain after the Second World War.

The British Nationality Act 1948 allowed those from Jamaica and Barbados, and others living in Commonwealth countries, full rights of entry and settlement, to help rebuild the British economy after the Second World War. The shortage of labour encouraged industries like British Rail and the National Health Service to heavily recruit from the Caribbean. Sam King initially applied to join the Metropolitan Police but was rejected due to his ethnicity. Instead he joined the Post Office, working there for over 30 years.

Despite having equal rights to British citizenship, new arrivals from the Commonwealth faced prejudice and abuse. 11 members of Parliament wrote to the government after the Windrush's arrival, complaining about "coloured" immigration. Afro-Caribbean Londoners were sometimes denied employment, housing, and even turned away from churches, pubs and dancehalls.

Empire Windrush: from Nazi troopship to symbol of change

The ship that would become the Empire Windrush, 1934

The Hamburg-Lloyd liner 'Monte Rosa' at the Greenwich Pier. The 'Monte Rosa' was renamed the 'Empire Windrush' after she was captured by the British at the end of World War II.

Sam King: "It was the first time in history you ever had a ship leaving Jamaica with about five hundred berths."

Try and get to the background, Jamaica is a colony. Boats do not leave from Jamaica to England apart from banana boats. Banana boats carry about 15, 20 passengers. They are normally students going to university, top fliers or civil servants going backward and forward. The average man do not come to rule. The average man do not get a chance to go on their own. And that’s what happened in the colonies. But by the grace of God, the Empire Windrush had taken immigrants from England to Australia, and had some British troops coming to Jamaica. Now we were ex-servicemen we would like to join the service in Jamaica but you can’t, because you’re from the colonies. They took certain men from England to come to Jamaica. But that troop ship had berth for about four, or call it five hundred people. And it was the first time in history you ever had a ship leaving Jamaica with about five hundred troop deck or berth.

This picture shows the Windrush in 1930, docked at the Port of London under the name Monte Rosa. Originally a German cruise ship, the ship was seized by the Nazi regime and used to transport troops during the Second World War. She was captured by the British at the end of the war and renamed the Empire Windrush. In 1948, she happened to stop over at Kingston, Jamaica, to pick up some British servicemen. Since the ship was not full, passage was offered to Britain for £28- if you travelled in the uncomfortable open berths of the "troop deck". Even this was a lot of money to the average Jamaican: Sam King remembers it as five weeks' wages, or about the cost of three cows.

People took passage on the Empire Windrush for many reasons: some were seeking employment in Britain, others hoped to rejoin the Army or Royal Air Force. Many simply had deep curiosity about the "mother country". Sam King described his desire to raise his children in a country with greater educational opportunities: "I didn’t want one of my children to be born in a colony."

The Empire Windrush's arrival on 22 June 1948 marked the beginning of a period of migration that would eventually see over 500,000 Commonwealth citizens settle in Britain between 1948 and 1971. This is now referred to as the ‘Windrush generation’. Even at the time Londoners saw it as a significant moment. Journalists and film crews crowded Tilbury Docks, although a sign on the ship warned passengers not to talk to reporters.

(Windrush segment starts 45 seconds in.)

One famous moment that has captured the spirit of the Windrush in song was a recording by Pathé news of the Trinidadian Calypso singer Aldwin Roberts (aka “Lord Kitchener”). He performed the specially-written song "London Is the Place for Me" live. His song most famously was played at the end of the first Paddington film in 2014.

Mixed reception

Sam King: "Once we arrived in England and we knew everything was all right it wasn't plain sailing."

What happened when the Empire Windrush docked?

Sam King: All right. About a day out they arrived they realized that we are going to dock and give the British their due they are reasonable fair. Once they had realized that we were going to land we were told that people who had somewhere to go - Go. The people who did not have anywhere to go they would provide accommodation at Clapham deep shelter. As it worked out it was a Jamaican Brian … oh … call him Brian who were in England who went to the Colonial Office and said look these people had nowhere to go. They seeking work you have to do something. And from what I can give the British authorities they came up, they send coaches to the docks at Tilbury and said if you had nowhere to go they didn’t encourage you if you had nowhere to go you could come to Clapham deep shelter and you will a bed and a blanket or whatever it is. And they did that. Once we arrived in England and we knew that everything was all right it wasn’t plain sailing.

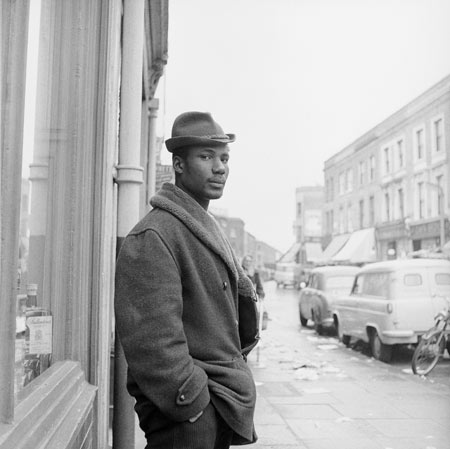

A man stands on a street, Notting Hill, 1961

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

Housing in London was in short supply following the bombing during the Blitz, and some Caribbean arrivals faced hostility for "taking" homes, or racism from Londoners who didn't want to live near black people. Predatory landlords charged Commonwealth citizens as much as double the rent of white residents in Notting Hill, and crammed them into slum-like conditions.

Windrush passengers without accommodation were temporarily housed by the government in Clapham South deep shelter, an air-raid shelter 15 storeys underground.

Sam King: "Good afternoon madam there’s a room for rent - Sorry no blacks."

Were

you looking for somewhere to buy or to rent or …

Sam King: Oh no, no. No, no. Not rent. You couldn’t get a place to rent. You’re a black man you knock on a door they…You have an ad. I’m not trying to say you wouldn’t get one. And there’s a room at Stockwell for rent you go, Good afternoon madam there’s a room for rent - Sorry no blacks. There’s nothing you can do.

The Irwin Clement Steel Band, 1964

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

The number of people living in Britain who were born in the West Indies grew from about 15,000 in 1951 to 172,000 in 1961. Due to a perceived “heavy influx of immigrants”, the British government created the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, barring the future right of entry previously enjoyed by citizens of the Commonwealth, which many considered a direct bar on people of colour.

Racism rooted in fear and mistrust erupted into violence in Notting Hill in 1958, when gangs of Teddy Boys roamed the streets attacking Black men (and murdering one, Kelso Cochrane from Antigua.) A Caribbean Carnival was held to try and improve race relations in 1959, later becoming the Notting Hill Carnival.

Notting Hill and Dale, which had been declining parts of the inner city, were gradually revitalised during the 1960s and 1970s. Some Afro-Caribbean new arrivals opened cafés and clubs, and Notting Hill gained a reputation as a bohemian area, attracting a young, trendy crowd of white as well as black people. Across London and Britain, the Windrush generation helped to rebuild the country from the devasation of the Second World War.

2018: commemoration and controversy

The Windrush generation has recently made headlines again: not for commemorative reasons but due to issues with the law relating to their immigration status. Despite being British citizens on arrival in the UK (many from colonies that were not yet independent countries), and having the support of the law and government at the time of their arrival, some of the Windrush generation or their descendants do not have proof of citizenship that satisfies subsequent governments.

Although many have spent most of their lives here, some of these individuals have been threatened with deportation if they cannot prove their right to remain in Britain. In 2009 the Home Office destroyed the passenger records of the Windrush, meaning it is impossible for some individuals to now prove they are in the UK “legally”.

150,000 people have called for an "amnesty” for those arriving between 1948 and 1971. Patrick Vernon, who created the petition, states: “As a country, we don’t recognise the Windrush generation’s contribution… their art and politics had a major impact on the community”. This too is not without controversy. David Lammy, Labour MP and the son of Guyanese passengers on the Windrush, has said that the term amnesty is offensive as it implies wrongdoing on the part of the passengers.

Learn more about the history of the SS Windrush and London's rich history of immigration at the Museum of London Docklands.