Building upon the museum’s digital collections, we recently decided to start collecting video games as an alternative way to tell the story of London. We have acquired 18 video games that represent or misrepresent the capital in their narrative or that were developed by Londoners. This is a new collection that spans from 1982-2000 and highlights the depiction of the city as a place and as a concept.

Interest in collecting video games as examples of art and design is currently at an all-time high. New York's MOMA recently acquired 24 video games including Pac-Man (1980), Tetris (1984) and Space Invaders (1978).

The Museum of London’s recent acquisitions explore and articulate the unique boundaries of video games as an art form and as an alternative path in the city’s social history that documents the fluidity and the evolution of London as an ever-changing city in a very interactive and engaging way.

The inclusion of video games furthers the mission of the museum around a new digital collecting area and ensures the ongoing preservation, social history study and interpretation of video games as part of the overall collection. By bringing these games into a public collection, the museum has the opportunity to investigate both the material science of video game components and develop best practices for the digital preservation of the source code for the games themselves.

But how is a city represented in the digital world? In a video game?

These are two completely opposite examples from our video games collection that show how London is being depicted from the very early video games to the more recent ones.

The first virtual worlds were text-based. Everything in them was described in words: the world, its inhabitants, the objects, the players, the events that occurred, the actions that the players undertook – everything. An amazing way to navigate a city without any visual props but only through imagination and experience. And now video games simulate incredibly accurate replications of the cities and their landmarks, offering an almost cinematic experience to the player.

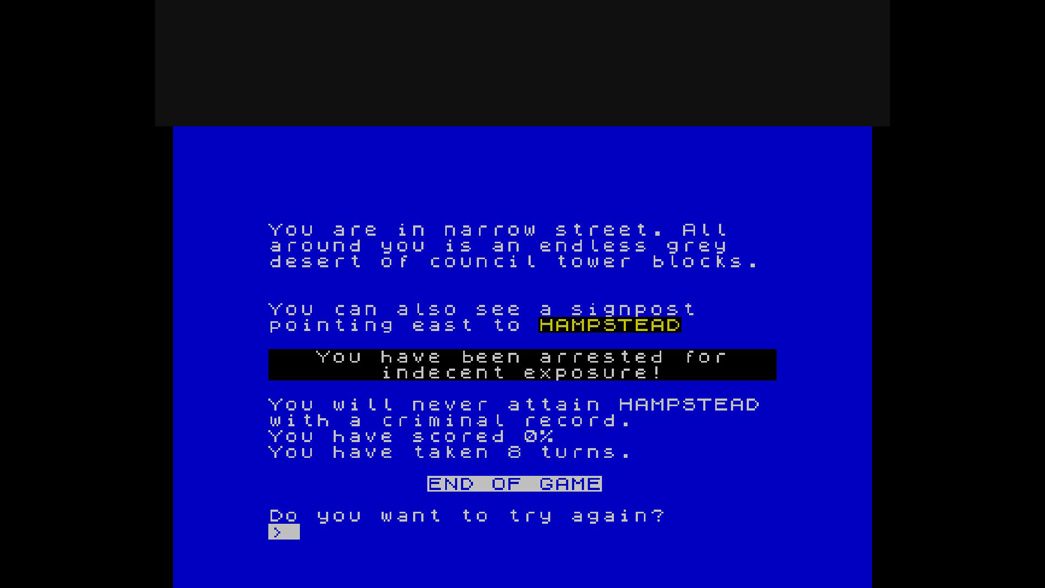

Early video games in the 80s tend to be very political and severely critique the socioeconomical situation in London. Hampstead, created by Trevor Lever and Peter Jones was made to be a parody of people who treated living in the Hampstead area as the ultimate badge of social success.

The aim of it is to reach the pinnacle of social status, and acquiring wealth is only one part of the problem. If you wish to go up in the world you also have to gain the admiration and respect of your fellow men, and there’s more to that than a fat bank balance.

A city is more than bridges, money, buildings and cables, more even than the social networks, lives and institutions within it. Cities are fluid entities that evolve and expand ceaselessly. Videogames, because they are experienced through motion and activity, have the capacity to depict a range of urban structures, representations, and systems.

London is a constantly moving wave of urban transformation and social change. The city expands, neighbourhoods change, landmarks pop up, and people blend in and weave the city. The greatest preserved feature of London is its own urban fabric. It’s not about Big Ben and its landmarks; it’s about capturing the essence of its fluidity, diversity and expansion. A place without boundaries but with people, emotions and memories.

In SimCity 3000 (UK Edition), the players assume the role of the mayor and they take control over London. SimCity 3000 is a city simulator—a dynamic model of urban life, complete with simulated citizens (Sims), traffic, commerce, industry, utilities, taxes, and other important aspects of city life. In this video game, London is not in the background, London is the narrative. Players interact with the city, engage and try to solve its issues. When playing the game, players’ performances are rated according to whether all goods, from industrial land to public schools, are being supplied at levels that equal a computer-calculated model of demand. The game allows numerous configurations of a limited number of building designs which imposes a universal aesthetic on the cityscape. Players can easily visually analyse the creation and the expansion of the city, but it also gives rise to homogeneous, class segregated neighbourhoods.