Ice-cream carts. Covent Garden Flower Girls. Costermongers. London's streets have always been thronged, bustling with vendors and the cries of hawkers. Rosalie Wiesner explores how encounters on London streets have inspired artists and photographers across the years.

As an avid photographer and people watcher, I have always been fascinated by life and activity on big city streets. I spent much of my childhood travelling from city to city with my parents. Something I will never forget is landing in Kathmandu, Nepal with my first camera and being told to entertain myself for an hour whilst my parents shopped. I walked along the bustling streets, filled with more people than I had ever encountered, on bikes and animal-drawn carts, market stalls sellers offering colourful fabrics and foreign foods. The new smells and unfamiliar faces will stay with me forever.

Frontispiece to the Twelve Cries of London, 1760

This is the title page from Paul Sandby's print series 'Twelve London Cries of London done from the Life'.

Ever since, I have been fascinated with the way artists have captured street life and found a way to bring it to life with a brush or through the lens. Our 2018 display, London Street Encounters, showed over 250 years of the capital's vibrant and ever-changing street life.

I discovered quickly that this has changed dramatically over the years. Some of the earliest images of Londoners selling their wares on the streets were produced in the 16th century and feature hawkers, beggars and even prostitutes who lived and made a living on the streets of London.

These depictions became known as ‘Street Cries’, referring to the lively calls from vendors that would echo through Europe’s cities. The early ‘Street Cries’ focused on sellers as ‘types’ and were very formulaic. As the subject was explored further by artists, the street sellers began to demonstrate individual traits.

What was also noticeable were the differences in the way the subject was rendered from country to country. The English portrait and landscape painter, Francis Wheatley (1747-1801) depicted the street traders in an idealised and sentimental way. His romanticised take on the subject and his exhibition of 13 oil paintings at the Royal Academy in 1792 resulted in the mass popularity of the Cries depictions in London.

A Broom Seller; Balais Balais, 1737

The French sculptor Edme Bouchardon, made a large number of drawings of Parisian street traders.

Many prints were made from Wheatley’s paintings; here’s one example of 13 mezzotint prints by Edward Stothard (1755–1834) published in 1918, after Wheatley’s painting of a turnip and carrots seller.

Even in the 1960s, Faith Eaton, a London doll maker and collector, made figures based on the Cries of London, mostly directly inspired by Wheatley’s paintings of the sellers.

In France the sculptor Edme Bouchardon (1698-1762) printed more realistic depictions of the ‘Cris des Paris’ with distinct traits, suggesting they were possibly based on individual people,no longer solely representing a ‘type’ of seller. These are less picturesque and formal in composition.Sitters demonstrate the realism of working on the streets. This woman selling brooms is rendered with expression, even emotion.

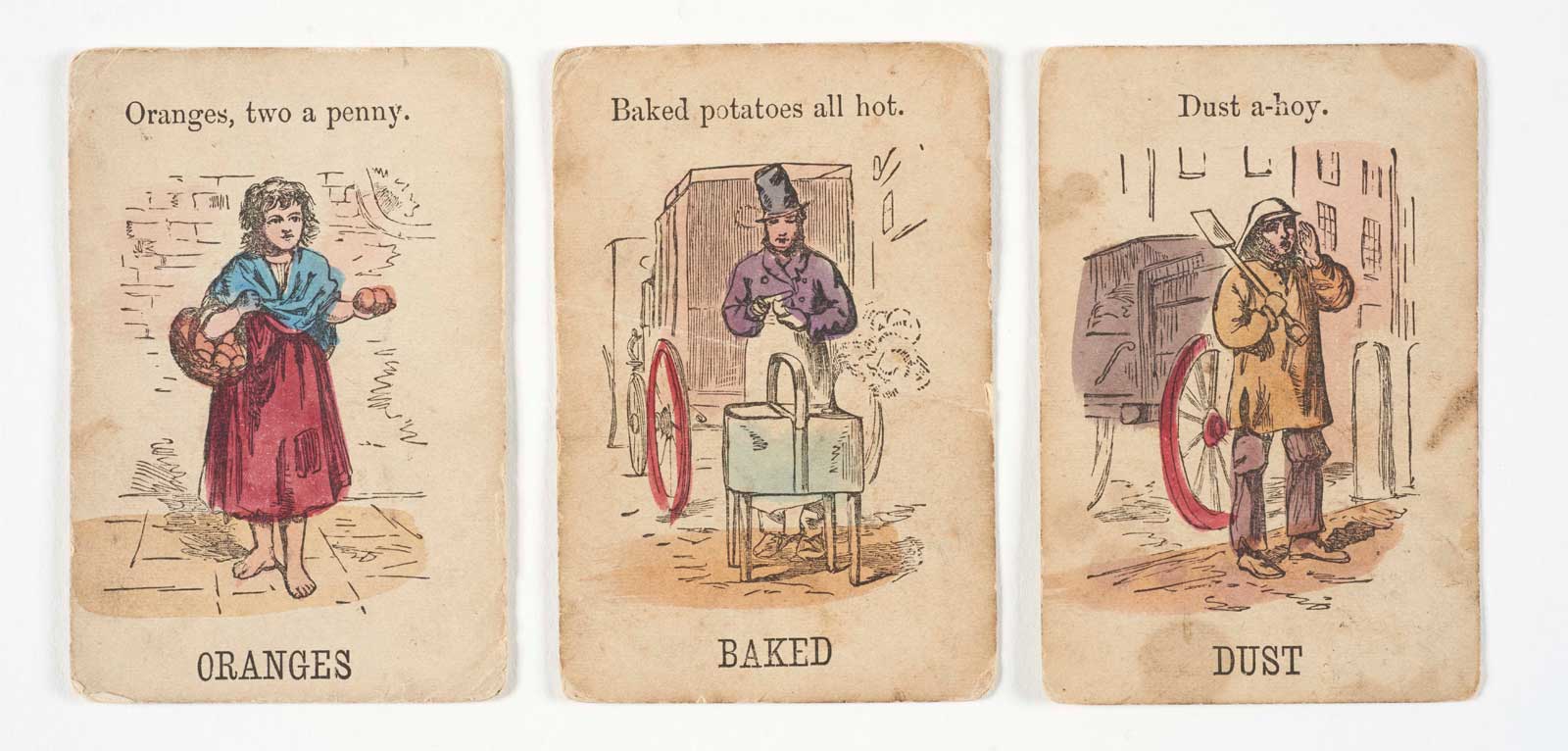

Art depicting the city’s street traders was extraordinarily popular. Our collection holds more than watercolours and etchings: I discovered many commercial artefacts ‘branded’ with street trader imagery, spanning hundreds of years.

We have a set of 17th century silver tokens with immaculately detailed engravings of ‘Street Cries’ (there are real expressions on their faces!) as well as a deck of 19th century playing cards. Each card depicts a street vendor and one word from their famous cry. Players would be awarded points when completing the trader’s cry by owning the full set of the same card. The longer cries had a higher value and awarded more points. Like today, designs from popular print culture of the time often feature on a variety of commercial goods, highlighting the popularity of the subject matter.

This photograph was one in a series of social documentary photographs taken by John Thomson and published in Street Life in London. Here Thomson shows customers gathered round the barrow of an ice cream seller.

A major development in the recording of the streets came with the invention of the camera in the 19th century. A pioneering photographer, John Thomson (1837-1921) set out to capture the circumstances of Londoners working on and around the city’s streets in this new medium. His work is recognised by many as the beginnings of social documentary. ‘Street Life in London’ (1877-78) was published as a series of booklets from 1877 to 1878, each containing a number of ’Woodburytype’ prints of Thomson’s photographs together with essays written by the radical socialist journalist Adolphe Smith (1846-1924).

The accompanying texts provided readers with contextual details about the lives of those photographed. They wrote in their Preface of ‘the precision of photography’ and the ‘unquestionable accuracy’ that would enable them to ‘present true types of the London Poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.’ In other words, photography is more trustworthy than art.

![Covent Garden flower women, c. 1877. This group of flower sellers are standing outside St. Paul's Church, their regular spot through generations. Whilst Covent Garden Flower, Fruit and Vegetable Market was a wholesale market, there was room for a few sellers of nosegays to passers-by. Poignantly, Adolphe Smith contrasts the life of these Covent Garden flower sellers with that of Isabelle, the favourite flower-girl of the Paris Jockey Club, who was well rewarded for her services. From a series of 37 photographs published in the book, 'Street Life in London' (1877), with text written by Thomson and the journalist Adolphe Smith. [p.8]](/application/files/1515/3718/5125/covent-garden-flower.jpg)

Covent Garden Flower Women, 1877

This group of flower sellers are standing outside St. Paul's Church, their regular spot through generations.

The subjects appear at ease or in some cases as if unaware of Thomson’s camera. We know that these pictures were posed, due to the long exposure times demanded by photographic equipment at the time. However, the images have a genuine quality, capturing each individual’s stance, gesture and expression.

As documentary and street photography developed further, artists from Europe brought new ideas and experimentation. When the camera became smaller and much more mobile in the 1930s, photographers were able to capture the liveliness of London’s streets in a freer and more spontaneous way, sometimes unnoticed! This way of observing the streets allowed for the opportunity to capture fleeting moments.

View from above looking down on a small crowd gathered round a watch salesman in Bacon Street, 1974

© Paul Trevor. All rights reserved.

Photographers embraced new angles, perspectives and social concerns. Henry Grant, Bob Collins, Roger Mayne and Paul Trevor are all well-known for their documentary photography from the 1950s to the 1980s. They also pursued this established practice of recording street markets and street vendors.

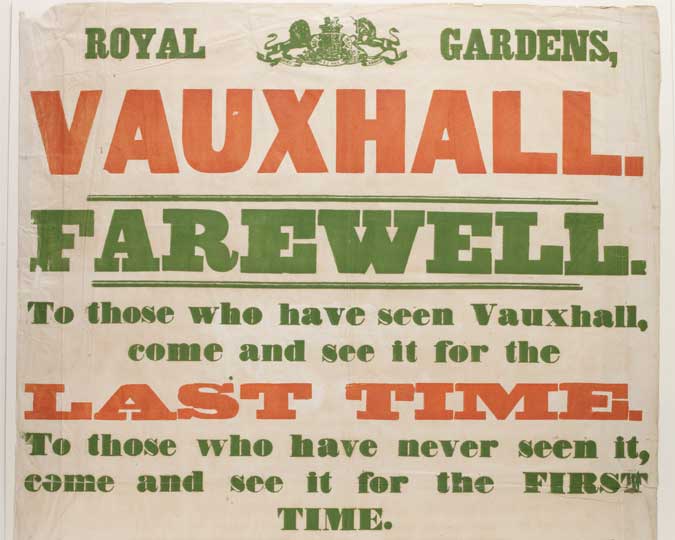

Ever-expanding shopping centres, and the convenience of online shopping, now threaten the bustling world of markets and street vendors familiar to Londoners for centuries. London’s streets will adapt to meet new demands, as they’ve always done, and image-makers will continue to find their inspiration on the streets. The images displayed in London Street Encounters demonstrate the enduring fascination to artists and photographers of London’s streets, its vendors and inhabitants. In turn, their choice of medium, varied techniques and approaches are as fascinating to us as to contemporary observers of their work.