The campaign for Votes for Women would not have been won in 1918 without the struggles and sacrifices of hundreds of brave Suffragettes. Today, we focus on just one: Emily Wilding Davison. Diane Atkinson, author of Rise Up, Women!, writes about the extraordinary life of a woman better known for her death, under the hooves of the King's horse on Derby Day, 1913.

Emily Wilding Davison, c. 1908

Emily is depicted in the portrait wearing her graduation robes, having studied at both Holloway (now Royal Holloway) college and St Hugh's Hall, Oxford.

In November 1906 the Women's Social and Political Union enrolled Emily Davison. She was thirty-four years old and employed as governess to the four children of Sir Francis Layland-Barratt, the Liberal MP for Torquay and High Sheriff for Cornwall. While her involvement with the WSPU remained low-key she continued working for the family until, eighteen months later, her urge to 'come out' as a militant would lead her to resign and join the campaign.

Emily was soon involved in Suffragette militant demonstrations.

In the afternoon of 30 March 1909, Dora Marsden, carrying a tricolour flag, led a deputation of twenty-nine women, Emily among them, to see Herbert Asquith at the House of Commons, although he had refused to meet them. Accompanied by a brass band and singing 'The Marseillaise', the women reached St Stephen's Entrance, but Dora Marsden, less than five feet tall, became tangled up with three police horses and the staff of her umbrella was broken. One Suffragette hit a constable on the head with her umbrella, other policemen had their helmets knocked off.

Ten women were charged with obstruction and assaulting the police, and sentenced to between one and three months. For Emily Davison, this was her first time in gaol; it would not be her last.

'Deputation Refused', Political 'peepshow' exhibited at the Women's Exhibition, May 1909

Depicting a group of Suffragettes being held back from a terrified Asquith and Lloyd George at the House of Commons.

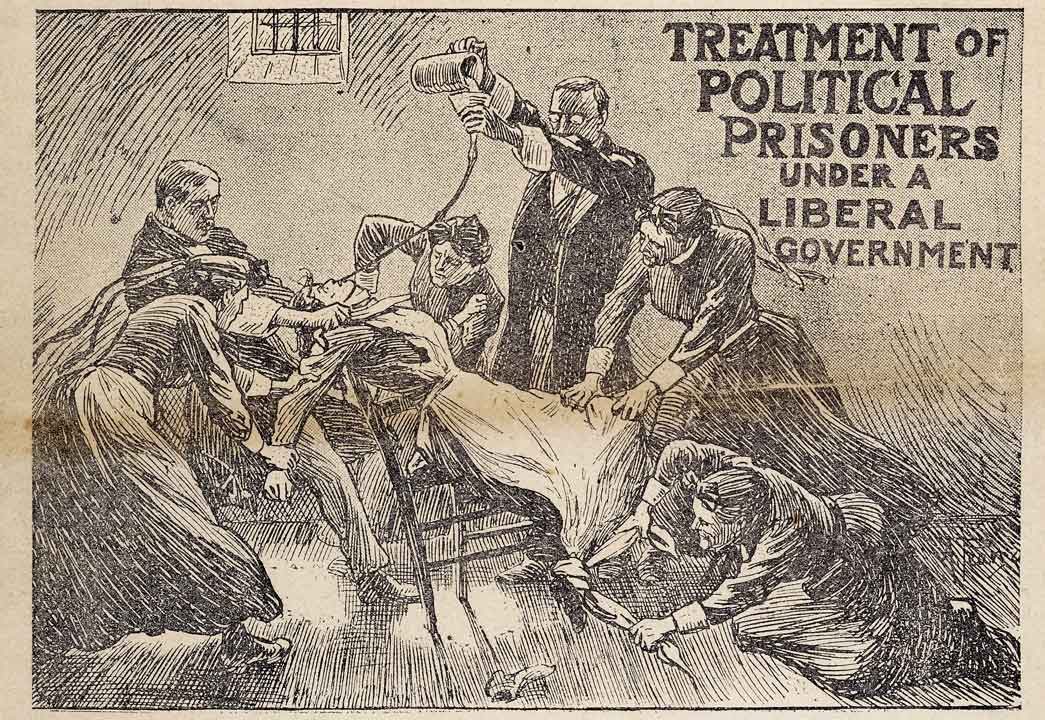

From resisting arrest, the Suffragettes proceeded to resist imprisonment. Demanding to be treated as political prisoners, they refused to be put in criminal cells, to wear prison dress, and fought back against prison wardens and matrons. They refused to eat, and prison authorities responded to these 'hunger strikes' with brutal force-feeding.

On 2 August, Emily Davison, whose prison file describes her as 'bad', wrote to Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary, from Holloway describing her treatment. Emily said she was 'forced' into a cell and broke seventeen panes of glass to let in some air. She was transferred to a cell where the glass was thicker but still managed to break seven panes, also cutting her hand. They stripped her and put her into a prison chemise; when the doctor tried to 'sound' her heart she resisted and was taken to a punishment cell.

'Ours is a bloodless revolution but a determined one' she wrote to Gladstone. Emily said that she and others were 'ready to suffer, to die if need be, but we demand justice!'

Emily Davison joined the dozens of Suffragette prisoners who were officially on hunger strike. In a manuscript prepared for the WSPU she provided a vivid account of the protest made by Suffragettes who were being kept in solitary confinement and force-fed in their cells. On 22 June 1912, near the end of a new six-month sentence in Holloway, she threw herself over the handrail and wire netting outside her second-floor cell and landed at the bottom of the steps of the floor below.

Earlier in the day she and others had barricaded themselves into their cells, 'a regular siege took place... on all sides we heard crowbars, blocks, wedges being used, joiners battering on doors with all their might. The barricading was followed by sounds of human struggle, the chair of torture [used for force-feeding] being pushed about, suppressed cries of the victims, groans and other horrible sounds.' She decided that she had to make a 'desperate protest' to end the 'hideous torture'.

Emily threw herself down the staircase outside the hospital wing, landing 'on my head with all my might.' She was knocked unconscious, but the prison authorities resumed force-feeding her through a nasal tube the next day.

Ten days before the end of her six-month sentence, on 28 June 1912, Emily Davison was released in a run-down state, two stone lighter, with two scalp wounds. She had been force-fed forty-nine times.

Emily continued her campaign of militancy by breaking windows, setting fire to postboxes, and attempting to assault Lloyd George. Despite her constant support for the Suffragette cause, she was never employed as a paid Organiser by the Women's Social and Political Union, and not all the articles that she submitted were published in suffrage newspapers.

Suffragette prisoners prepare to parade in Hyde Park, 1910

Emily Davison is second from right, in her academic robes.

Joan of Arc statue displayed at the WSPU Summer Fair and Fete, 1913

From a postcard produced after Emily Davison's funeral

The Daily Sketch published Emily’s last article on 28 May 1913. The language of ‘The Price of Liberty’ is apocalyptic. ‘The perfect Amazon is she who will sacrifice all … to win the Pearl of Freedom [the vote] for her sex. Some of the bounteous pearls that women sell to obtain freedom… are the pearls of friendship, love and even life itself.’ Emily refers to the ‘terrible suffering’ she has endured, the loss of ‘old friends, recently- made friends, and they all go one by one into the Limbo of the burning fiery furnace, a grim holocaust to liberty’. She argues in favour of making ‘the ultimate sacrifice’, happy to pay the ‘highest price for liberty’.

Emily had agreed to be a helper at the Suffragette Fair and Festival at the Empress Rooms, Kensington, on Derby Day, but she decided to visit the fair the night before, and discussed with Kitty Marion and others ‘the possibility of making a protest on the race course, without apparently coming to any decision’. As the women strolled into the festival, they were faced by a statue of Joan of Arc, bare- headed and holding her sword pointing to heaven. On the plinth were emblazoned Joan’s reputed last words: ‘Fight On and God Will Give the Victory.’

The weather on Wednesday 4 June 1913 was forecast to be sultry with thunderstorms. That morning Emily left Alice Green’s home at 133 Clapham Road, Lambeth, and walked to Oval to catch a tram to Victoria station, where she bought a return ticket for Epsom Downs. Before she left she told Alice what she was going to do. She pinned a purple, white and green flag inside her jacket and took her latch key, a small leather purse containing three shillings and eight pence and three farthings, eight halfpenny stamps and a notebook. Another suffragette flag was tucked up her sleeve. Emily walked to the racecourse and bought a Dorling’s List of Epsom Races.

Emily made her way to Tattenham Corner, a tricky place for horse

and rider in the gruelling mile and a half race. This was the biggest

day out in Edwardian England. Here at three o’clock, the apex of the

social pyramid met its base. The King and Queen and their entourage

added glamour to an occasion that welcomed both the establishment

and the working class at play.

Emily squeezed close to the rails. As the race started the sixteen

horses and riders ran straight for three furlongs before the course

climbed to a gradient of one in fifteen. The King's horse, Anmer, made a good start. At

seven furlongs the field took the left turn downhill for five furlongs

and this is where Anmer fell away to the group at the back. The leading

horses pounded towards the spot where Emily was waiting. Tons

of horseflesh and men flashed past, spittle, sweat, huge eyes rolling

with the effort, the noise of the crowd was bewildering. Everyone was

screaming the names of their horses for that brief moment, and jumping

up and urging them on. The trailing bunch, including Anmer,

approached. Emily fiddled with the sleeve of her jacket, bobbed under

the white railings, and made history.

Clutching her unfurled tricolour of purple, white and green, Davison dashed out to make her protest at the lack of progress on women’s suffrage in general, and the treatment of Mrs Pankhurst in particular. By targeting Anmer she was reminding King George V of his government’s callous injustice to women. Emily stood with her arms above her head, and then stepped in front of the jockey, Bertie Jones and tried to grab the horse’s bridle. She was knocked over screaming.

‘The horse struck the woman with its chest, knocking her down among the flying hoofs … and she was desperately injured … Blood rushed from her mouth and nose. Anmer turned a complete somersault and fell upon his jockey who was seriously injured,' the Daily Mirror reported.

Oblivious to what was happening the spectators who stood to the left of Emily turned to follow the race, but those to the right of her were puzzled by what was happening in front of their eyes. There was chaos: the jockeys behind Jones cursed and struggled to pull away from the woman who had invaded the track. Anmer cantered off with a few cuts to his face and body, apparently none the worse for his fall.

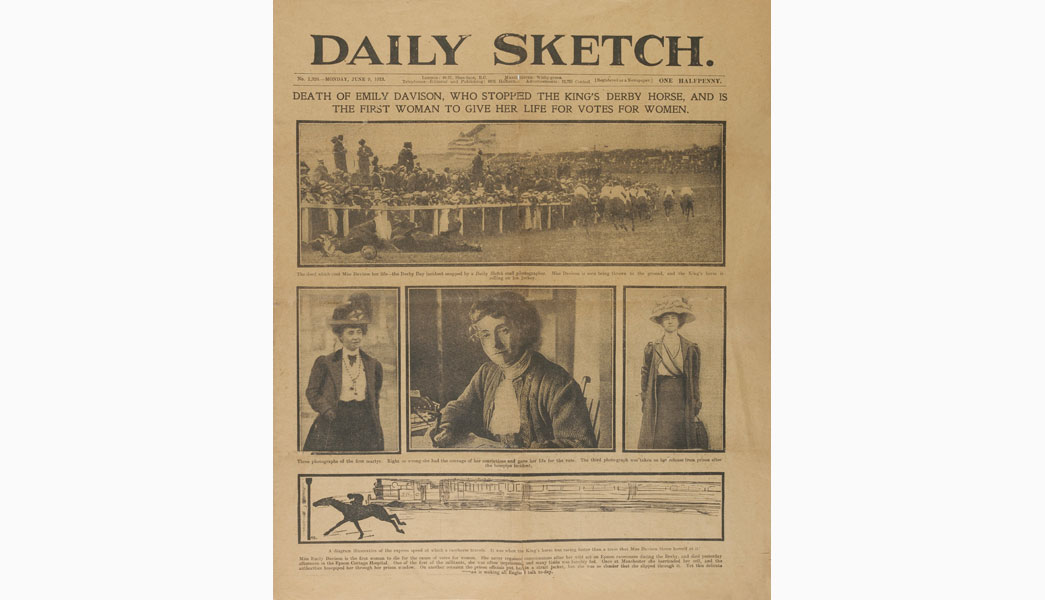

Daily Sketch newspaper, dated 9th June 1913

The headline: 'Death of Emily Davison, who stopped the King's Derby Horse, and is the first woman to give her life for Votes for Women'

There were film cameras at Epsom that day to satisfy the Empirewide demand for stories about the royal family and Derby Day. Emily’s deathly dash was recorded on film and history was made on twenty feet of silver nitrate. She became the most famous suffragette, a heroine for all women who struggled for equality. Her jerky movements on grey, grainy film have played for a hundred years. Shots of the film were made into stills and distributed to the press ready for the first edition of the next day’s newspapers. At Newmarket they called Emily ‘that malignant suffragette’.

On 8 June, Emily died from her injuries, surrounded by an honour guard of Suffragettes in a room hung with green, white and purple bunting.

A letter from Emily’s bewildered mother lay on her bedside table: ‘I cannot believe that you could do such a dreadful act. Even for the Cause which I know you have given up your whole heart and soul to, and it has done so little in return for you. Now I can only hope and pray that God will mercifully restore you to life and health and that there may be a better and brighter future for you.’ There were cards from well- wishers, a fan letter from a lunatic in Banstead Asylum and two poison- pen letters, one from an ‘Englishman’ who hoped she suffered ‘torture’ until she died: ‘I consider you are a person unworthy of existence … and I should like the opportunity of starving and beating you to a pulp.'

On 8 June the WSPU’s creation of spectacle began. Emily was given a ceremonial funeral for her ‘noble sacrifice’ and the dues of ‘a fallen warrior’, ‘a brave comrade’ and ‘crusader’.

The Funeral of Emily Wilding Davison, 14 June 1913

The image depicts one of the banners carriers in the procession bearing the defiant message 'Fight on & God will give the Victory'

On Saturday 14 June 1913, a special guard of honour of Emily’s closest friends brought her body from Epsom to Victoria railway station. Six thousand women marched from Buckingham Palace Road to Emily Davison’s funeral service at St George’s Church, Bloomsbury. Ten brass bands marched behind each section playing funereal marches.

The coffin was escorted by Elsie Howey on a white horse dressed as Joan of Arc, and two contingents of hunger strikers walked behind the hearse which was laden with wreaths.

Banners in purple silk included Joan of Arc’s last words: ‘Fight On and God Will Give the Victory’. Central London stopped.

This article is excerpted from Rise Up, Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. Diane Atkinson's book, published by Bloomsbury, is a collective biography of the Suffragette movement, illuminating the lives of more than a hundred women who took part in the militant campaign between 1903 and 1914.

Diane, why should we still remember the Suffragettes, 100 years on?

It is essential to keep the memory of the campaign for votes for women alive. Recently It has become clear that most people know very little about this subject, and yet this was a dangerous and painful struggle for a basic human right. Every woman needs to know the story of how their Edwardian sisters struggled, and what they suffered and sacrificed so that we can vote.

What do you think was the most important thing in winning women the right to vote in 1918?

The suffragette campaign which thundered around the country in the years leading up to the First World War, and the work done by women who fought the War on the home front, were to me, the major factors leading to the granting of the first instalment of the vote one hundred years ago. While the Suffragettes were deeply unpopular at the time, the thought of a renewed and reinvigorated Suffragette campaign if women were not given the vote despite their vital role in the War, was not to be contemplated.

You can contact Diane Atkinson on Twitter, @dithedauntless.