The east London docks were built, in part, to trade in slave-harvested goods from the Caribbean. Curator Danielle Thom has mapped the traces of the Atlantic slave trade that remain in Docklands, hidden in street names, statues, and what was built with the profits of slavery.

Update, 17 June 2020

On June 9th 2020 the Museum of London made a public statement regarding the Robert Milligan statue that stood in front of the Museum of London Docklands. Later that day, the statue was removed by local authorities, in response to a worldwide movement to remove statues which commemorate supporters of slavery.

The legacy of the Atlantic slave trade is long, and it casts a shadow to this day. The Museum of London Docklands is surrounded by buildings, streets and statues built with the profits of slavery, in many cases commemorating the owners and traders of enslaved people.

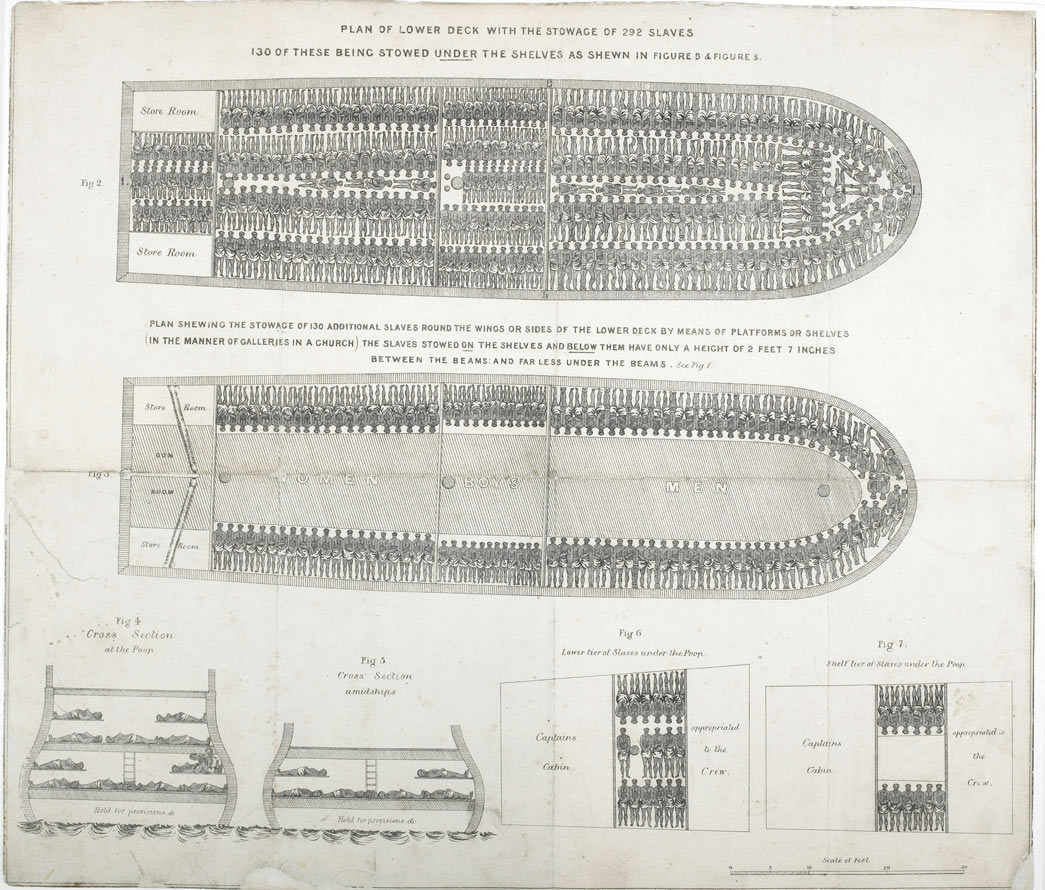

The British trade in enslaved African people was ended in 1807, and the legal condition of slavery abolished throughout the British empire in 1833. These dates are celebrated as the end of a pernicious global system of exploitation and violence, lasting three hundred years, in which approximately eleven million African people were transported across the Atlantic in bondage. This figure does not even begin to count the estimated several millions who died before reaching land.

An end to slavery, however, did not equal an end to its

social, financial and cultural effects. Two centuries after the trade was

abolished, Britain’s economy and cultural heritage remains inextricably tangled

with the after-effects of slavery; a tangle which we are only beginning to

recognise in full.

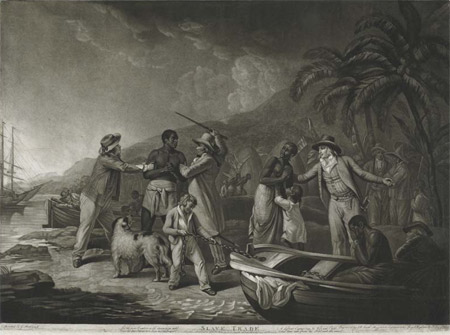

Print based on George Morland’s painting, depicting an African family being captured and separated by European sailors compelling them to lives of slavery.

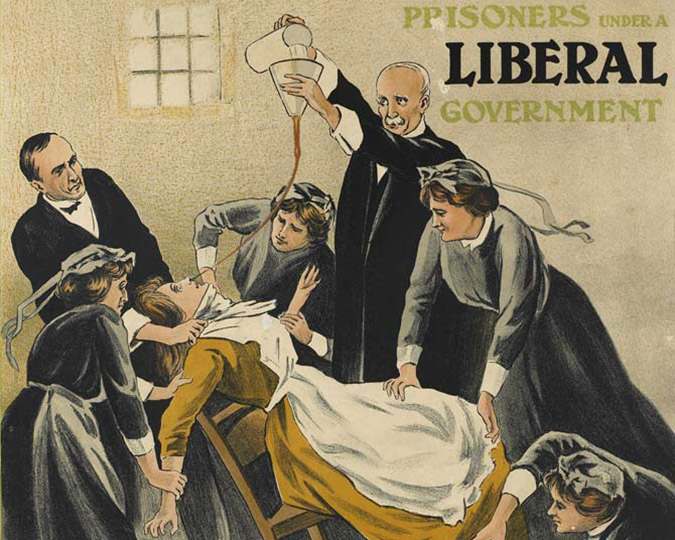

The process of abolishing slavery throughout the empire was one founded on an unpalatable political compromise. The British government raised £20 million (more than £16 billion, in today’s currency) in order to pay out compensation claims. Compensation, perhaps, for the hundreds of thousands of people then living in slavery? No: compensation for slave owners, to repair the financial damage caused by the sudden loss of unpaid labour.

The vast sums of money doled out by this compensation scheme, on top of the profits already generated by slavery and its associated trades (such as sugar trading and ship insurance) consolidated wealth in the hands of an upper and upper-middle class elite.

This gathering of capital equalled a gathering of influence: the money earned from slave labour and, later, from compensation was used to purchase artworks, fund political campaigns, underwrite businesses, build cities and endow institutions. Even today, many wealthy British people enjoy the benefit of inherited fortunes which, eight to ten generations ago, were created or augmented by slavery.

Harewood House, Yorkshire, seen from the garden

Built for wealthy slave owner Edwin Lascelles. Photo by Gunnar Larsson.

Many of the most significant collectors and donors to British museums, such as John Julius Angerstein and Hans Sloane, were plantation owners, slave traders and/or involved in the trades that directly propped up the slave economy. Slave-owners such as Edward Colston and Christopher Codrington used their profits to support and endow libraries, hospitals and other institutions; being commemorated in statues and public monuments for their trouble.

The construction of numerous stately homes – like Harewood House, home of the Lascelles family – was funded by slavery profits, and these are today open to visitors. London’s West India Docks, a major infrastructure project begun in 1802, were not only funded in part by slavery profits, but actually designed to enhance those profits by making the import of slave-grown goods more efficient.

The legacy that slave-traders have left behind can be uncomfortably close to home. Robert Milligan, a slave-owner who settled in London, was the driving force behind the docks' construction. Upon his death in 1809, he owned 526 enslaved Africans who were forced to work on his family's plantation in Jamaica. The West India Docks company erected a statue in his honour. It now stands in front of the Museum of London Docklands, itself a converted warehouse once used to store slave-harvested sugar.

Portrait of George Hibbert, 1811

By Thomas Lawrence

George Hibbert, one of the slave traders and plantation owners who championed the construction of the West India Docks, is the subject of a display at the Museum of London Docklands which addresses this cycle of profit and influence. Part of a family network of slave traders and sugar plantation owners, Hibbert was fabulously wealthy. He poured money into his personal collection of books and artworks – including rarities such as a Bible inscribed by Martin Luther – and had a passion for botany, funding scientific expeditions around the world to collect plant specimens. There was even a genus of flower named after him.

Hibbert donated money to charitable causes, including hospitals and poor-relief committees, and was one of the founders of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute. He also used his wealth to fund a political career, and was elected as an MP in 1806. As an MP, he lobbied vigorously for the preservation of slavery, arguing against William Wilberforce and other abolitionists, and claiming that slavery was a necessary part of the British economy, keeping profit margins high and trade goods in ready supply.

Such was the reach of the slave economy, and so heavily integrated was it into British life, that seemingly innocuous things like botany, hospitals, and even lifeboats, were funded by it. However, the long-term effects of slavery were not solely economic. It wasn’t simply a question of building wealth and channelling that into cultural and social endeavours. The very idea of racial difference and identity was underpinned by slavery. The evil effects of this continue to be felt, two centuries after the end of the trade.

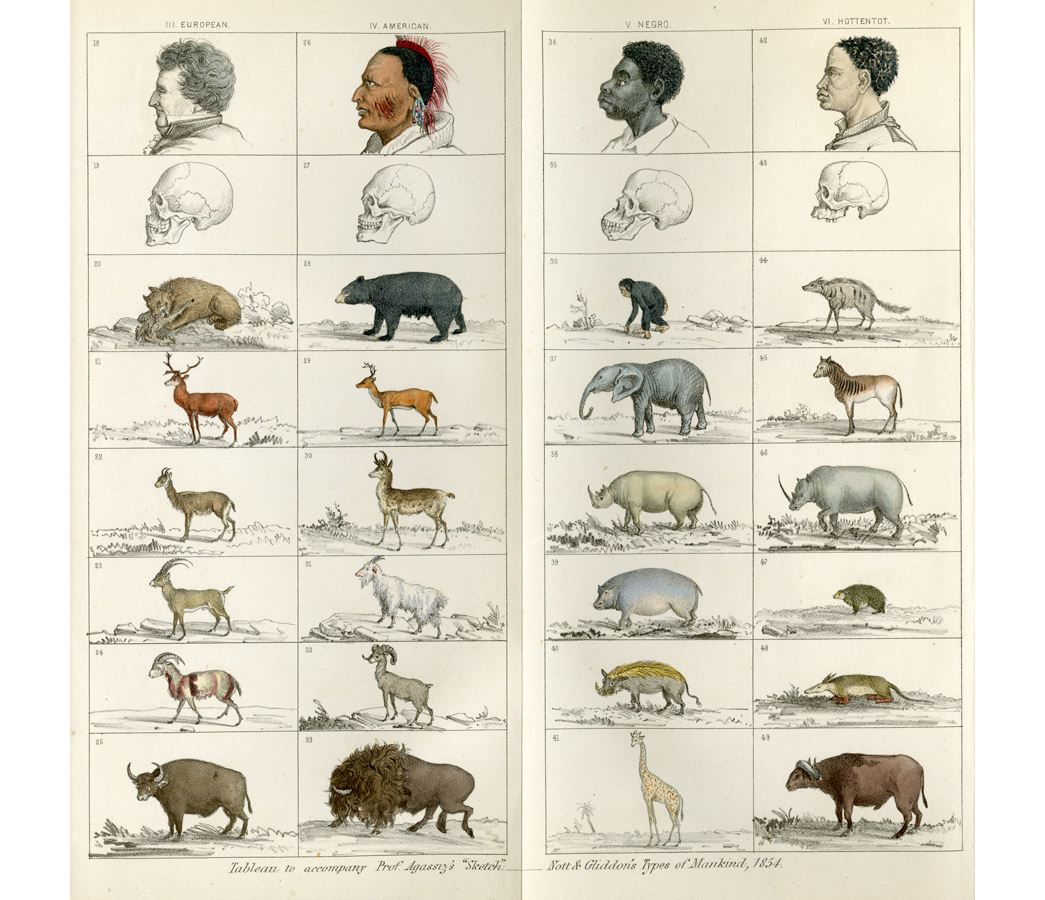

Diagram depicting the different "types of mankind" and animal in different climates, 1854

Collection of Harvard University

During the eighteenth century, broader shifts in the European understanding of science prompted new ways of thinking about race and ethnicity. In the 1730s and 40s, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus developed the concept of ‘taxonomy’ – the organisation and classification of living things. As these concepts developed, they were used to construct categories and hierarchies of race in humans. This ‘scientific racism’ was in turn used by Europeans to justify the enslavement of African people. The vast wealth that slavery brought to Britain encouraged those who profited to believe the people they enslaved were mentally and morally inferior.

Photographer Neil Kenlock. The museum's collections include hundreds of sources documenting centuries of racism against black Londoners.

False assumptions about the intelligence, morality, physical ability and health of people of African descent are still made today, which affects public policy and private life. Indeed, the wider relationship between the British empire, trade and scientific racism has impacted on the lives of all non-white people, including those of Asian heritage. Housing provision, education policy, policing strategy, medical outcomes, employment statistics – all of these things are inflected by the idea of racial difference; sometimes consciously, sometimes not.

The over-representation of black children among child poverty statistics, and their under-representation among university graduates, for example, are not random coincidences, nor are they caused by ‘innate’ racial characteristics. The structural racism with which British society grapples today is a direct consequence of cultural attitudes, economic policies and social constructs rooted in the slave trade.