As Hallowe’en nears, witchcraft is in the air- and on display. In 2018, we loaned seven mysterious and magical “witch bottles” to Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum for their exhibition Spellbound: Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft. Let’s peer inside these sorcerous vessels and see what they can tell us about magical beliefs, past and present.

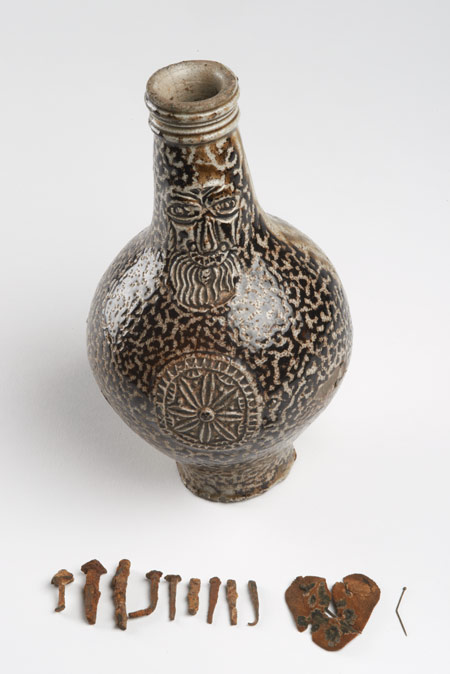

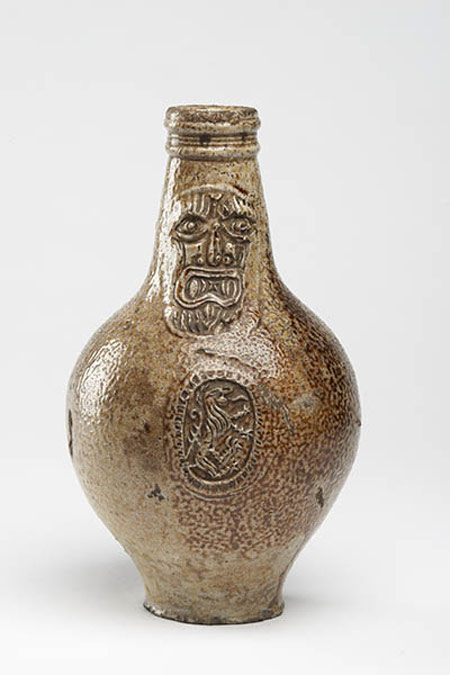

17th century stoneware Bartmann jug used as a witch bottle. Found containing a heart-shaped piece of felt pierced with pins, and eleven nails.

The Museum of London’s collection includes several 17th century stoneware pots, found buried in sites across the city. In appearance, they’re much like the hundreds of examples of early modern pottery we hold- until you look inside. Each was found stoppered and filled with a bizarre assortment of objects including iron nails, lead shot, bundles of hair, and a heart-shaped piece of felt pierced with pins. Their contents mark them as “witch bottles”, magical talismans used by past Londoners to ward off spells or cure disease. When they were buried, they were probably also filled with a final, vital ingredient: the urine of the person who wanted protection.

A selection of our witchiest bottles were on show in the 2018 Spellbound exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. They are just a few of the hundreds of objects on display, spanning eight centuries, that explore how our ancestors used magical thinking to cope with the unpredictable world around them.

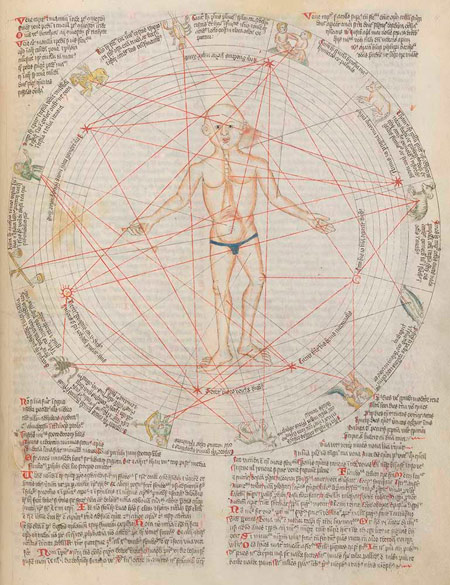

Microcosmic man, 1420 © Wellcome Library, London

© Wellcome Library, London

Matthew Winterbottom, one of the curators of Spellbound, explains: “Magical thinking is the belief that your thoughts or actions will have an effect on something that can’t possibly be logically connected. Performing a ritual action, trying to cast a spell on someone, carrying a lucky charm- all examples of magical thinking. Extreme emotions tend to encourage magical thinking- people who are falling in love or are living in fear are driven to it.”

That helps to explain why magic was so attractive to people living in past eras. “Particularly in the medieval era, it’s a much more dangerous world and death is always just around the corner- that encourages people to try and influence their fates with magic. This worked in tandem with the official religion of the church: they had a model of the cosmos filled with devils and angels. To the common people there was little perceptible difference between prayers to a saint and magic spells to conjure a spirit.”

In fact, our so-called “witch bottles” were probably used not by witches, but to protect against them. According to the folklorist Ralph Merrifield: “the supposed victim of witchcraft would put some of his urine in a bottle with pins or needles, and bury it, believing that this would inflict acute pain on the witch, who would be unable to pass water until the spell had been removed.”

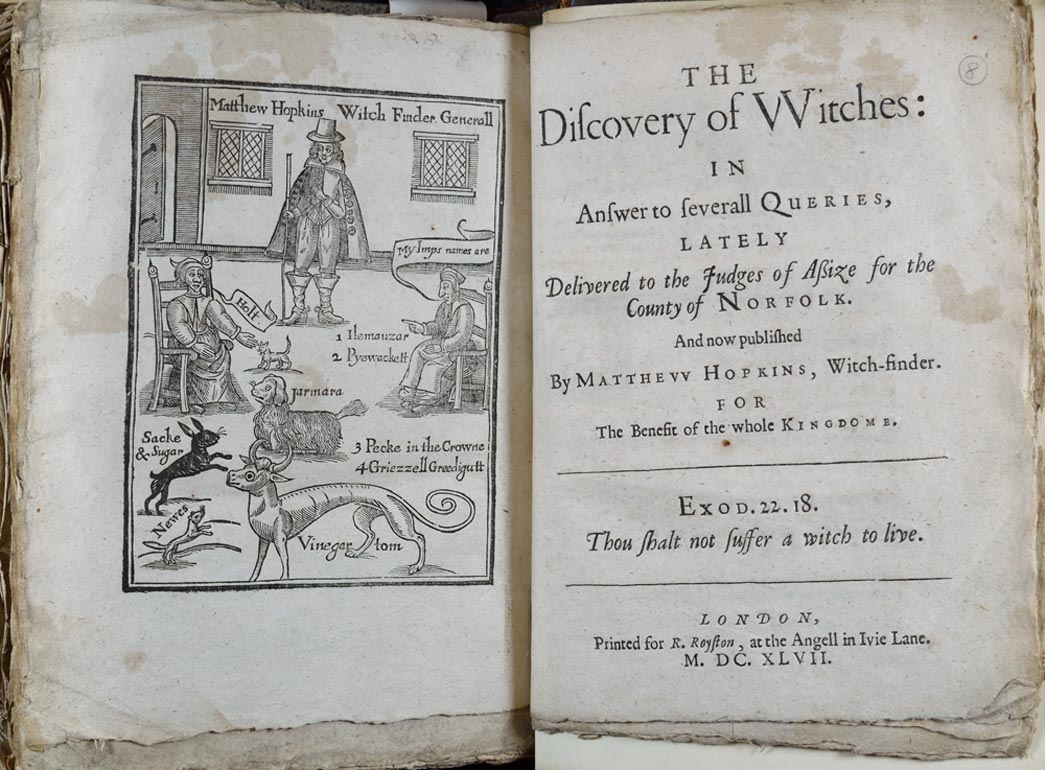

Belief in witches in Europe reached its height in the witch-craze from 1450-1700, a religious and moral panic that killed perhaps 100,000 people accused of witchcraft via official execution, torture, or illegal lynching. In England, the process was controlled by the courts, with witches- usually but not always women- accused of “maleficium”: causing harm by using magical spells.

Matthew Winterbottom: “We have this whole section of the witch craze, how accusations come about. It’s worth mentioning that of people tried for witchcraft in England, about two-thirds of them were acquitted.” This supposed leniency of the law led to popular demands for protection from witches. Spellbound includes exhibits on the self-styled “Witchfinder General” Matthew Hopkins, who operated in Essex towns gripped by a witch-panic during the English Civil War. In three years, he caused about 300 women to be hanged for witchcraft. Other people turned to counter-magic, to talismans or charms to guard them against hostile spells- like our witch bottles.

Found containing earth, hair and a cloth heart stuck with bent pins.

People certainly believed in hostile magic, even after the worst of the 17th-century witch-panic had died away. Joseph Glanvill wrote in his Sadducismus Triumphatus (1681): “William Brearley’s landlady was cured from a spell put on her. She was haunted by visions of a bird flapping in her face so she peed into a bottle containing pins, nails and needles, corked it and buried it. She started to get better and found out that a man in a nearby town had died suddenly and everyone assumed that he must have been the witch.”

Here, we see that the malady afflicting the landlady, incurable by contemporary medicine- perhaps even wholly psychological- was helped by performing a ritual action. Magical thinking gave this woman a sense of agency over her illness, a way of taking control of a mysterious world. That’s why magic was- and remains- so appealing.

Witch in a bottle © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

Matthew explains: “It’s not just historically: we want people to think about their own magical thinking. We all have some superstitious beliefs, no matter how rational you think you are. There’s a ladder at the entrance to the exhibition, and in order to get in you have to walk either under or around it. I am a definite walker-around. Magical thinking is part of the human condition.

“Perhaps the most shocking question in the exhibition relates to one specific object: do you think this bottle has a witch in it? It’s a glass bottle that was given to the Pitt Rivers museum by an old lady, who said ‘There’s a witch in it and never open it or there’ll be a peck of trouble.’” The bottle has never been opened to this day.

Modern witch bottle found on the Thames foreshore

For display in Spellbound, the human teeth have been replaced with replicas.

The Museum of London collection shows the persistent power of magical belief: one of the witch-bottles on loan is a plastic pill bottle, not exactly common in the 17th century. It was found on the foreshore of the Thames, containing slivers of metal, coins, a tiny bottle of oil of cloves- and a large number of human adult teeth. The latest coin dates from 1982. Whoever threw this grotesque totem into the river clearly believed in the power of ritual magic, far into the twentieth century. Oil of cloves is often used to treat toothache, so the witch-bottler may have been pleading- or giving thanks for- relief from tooth pain.

Like the other objects on loan to the Ashmolean, these bottles help Spellbound show the richness and strangeness of magical beliefs. Matthew says the exhibition includes objects from as far afield as a demon-summoning mirror from Dresden, and as unusual as a witch’s poppet from Boscastle’s Museum of Witchcraft. “Loans are absolutely central because even the most encyclopaedic collections do not have everything you need for an exhibition. And it’s a way for all museums to help each other. Particularly given the severe cuts to many museums’ budgets, loans and touring exhibitions are essential to making our shared history accessible.”

Museum of London registrar Helen Copping said: "As one of the world's largest urban history museums, the Museum of London lends to exhibitions around London, the UK and the world so that our collections can reach as many people as possible. One of the most rewarding aspects of lending is that it allows our collections to be seen and interpreted in new contexts, alongside objects they might not otherwise be connected with. Sharing our collections in this way helps build new and existing relationships with other museums, and promotes a wider understanding of London’s history, archaeology and contemporary culture."

So next time you suspect you've been cursed by a witch, try this recipe, from Joseph Blagrave's Astrological Practice of Physick, 1671:

"Another way is to stop the urine of the Patient, close up in a bottle, and put into it three nails, pins, or needles, with a little white Salt, keeping the urine always warm: if you let it remain long in the bottle, it will endager the witches life: for I have found by experience that they will be grievously tormented making their water with great difficulty, if any at all, and the more if the Moon be in Scorpio in Square or Opposition to his Significator, when its done."

Happy Hallowe'en!

The Museum of London makes our collections accessible through an intensive programme of short and long term loans to a number of partner institutions in London, the UK and abroad.