For over a decade, one of the biggest archaeological digs in London's history has been going on right under our feet. As part of the Crossrail project, archaeologists have excavated from Reading to Woolwich, racing to uncover the city's past as the new Elizabeth Line was dug. Jackie Keily, curator of our 2017 Tunnel exhibition, reveals how they did it.

Ballast removal in the Crossrail tunnel, 2012

One of the largest construction projects in Europe has been going on beneath London's streets for over seven years. © Crossrail

The Tunnel exhibition (2017) at Museum of London Docklands told the story of the archaeological work undertaken as part of the Crossrail Project. The building of the Elizabeth line from Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east to Heathrow and Reading in the west has been one of the largest construction projects in Europe. It has been accompanied by a huge programme of archaeological work, undertaken under the supervision of Crossrail’s Project Archaeologist, Jay Carver. The archaeological aspect of the project has gone on for approximately 14 years in various forms, including over six years of excavation.

UK planning law requires some form of archaeological work if it is deemed likely that a construction project will disturb archaeologically significant layers. In London, it is hard to avoid areas of archaeological significance. Human habitation in the area dates back over 10,000 years and there has been an urban centre in the City of London for the last 2000 years (give or take a few hundred years from c. 450 to 850AD after Roman Londinium was abandoned).

With a project like Crossrail, which would tunnel right across London from east to west – and right through the middle of some of the most historically significant areas of the city – a well-structured and well-funded archaeological programme was essential. Having appointed a team of archaeologists, headed up by Jay, to supervise and oversee the programme, they began to research where the excavations should take place, working closely with Historic England. Crossrail then set about appointing archaeological contracting units to do the actual excavation.

Archaeologists from MOLA excavate a site at North Woolwich

Every stop on the Crossrail line has some fascinating archaeology beneath it. © MOLA

Many archaeological units operate in London. Most of the work on the Crossrail project was undertaken by MOLA (short for Museum of London Archaeology, now completely independent from the Museum of London) and Oxford Archaeology Unit. But before any excavation took place, before a trowel scraped the soil’s surface, many hours of research and desk-based work were undertaken.

This is an important part of modern commercial archaeology: the aim is to try and find out as much as possible about the site before you start to dig. This allows you to estimate how long you may need to do the excavation and how complicated the archaeology might be. This is far from an exact science. Much of the research is based on looking at the local history of the area, finding out what archaeology has been done in the area before and researching the soil types and geology, to estimate the likely preservation of artefacts. Based on this information and taking the construction programme into consideration, a programme of works is then agreed, so that the archaeologists know their budget and how much time they will have on site.

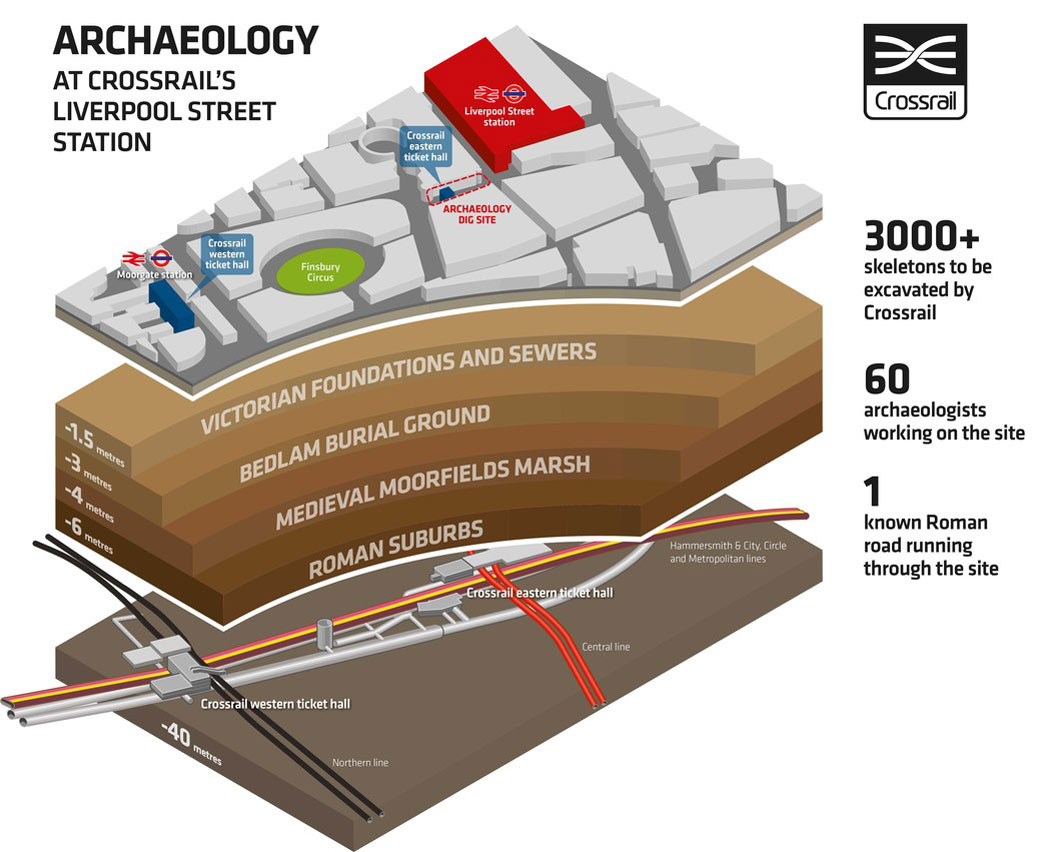

The skeletons of Liverpool Street

A good example of the potential of such background research is at the large Crossrail site at Liverpool Street. There's a large body of pre-existing archaeological work on sites in this area, which indicated what might be found. One of these is an earlier excavation at Liverpool Street Station, just to the north of the Crossrail site, which took place in 1985, when the old Broad Street Station was redeveloped into the Broadgate complex. That excavation, known by the site code LSS85, found evidence from the burials of the New Churchyard – the vegetable garden of Royal Bethlem Hospital (also known as "Bedlam"), which was transformed into a burial ground in 1569. There were bodies and grave markers from earlier Roman burials too. It was extremely likely that the Crossrail dig would also find human remains.

Roman timber gate at the edge of Walbrook stream

Excavated underneath Liverpool Street. © MOLA

The archaeologists also knew that this site lies very close to a now-buried river, the Walbrook, which flowed south to the Thames. This was an important source of water in the Roman period and we know from earlier archaeological work that many industries were located along or near it. It also created a landscape that was quite water-logged and liable to flooding and land reclamation. These conditions are perfect for the preservation of organic materials, such as timber and leather, materials that do not survive on drier sites. The discovery of timber revetments and leather shoes came as no great surprise, although we could not have predicted the fascinating discovery of a pair of Roman wooden gates, reused as a platform on the banks of the Walbrook.

For the post-Roman period there is also a plentiful supply of documentary evidence to research. This became an important part of the Crossrail project: extensive research into the burial registers from various city churches, whose parishioners were buried in the New Churchyard. As one moves into the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries the presence of wills, legal documents and newspapers adds further evidence and information.

So with this one example, it is possible to see how a picture of the site can be built up long before the actual excavation begins. The archaeologists were delighted, but not surprised, to uncover a 16th-17th century burial pit once digging started at Liverpool Street.

Inside the Tunnel exhibition

Human remains and archaeological objects excavated during the Crossrail exhibition

On site, archaeology is very much part of the construction project and adheres to the same rules, in terms of health and safety and working practices. For example, at Liverpool Street the archaeologists worked in shifts, the same as the construction workers, so that the site would be ready in time and all the archaeology recorded. They also wear the same protective clothing and helmets (known as PPE) as the construction workers. You can find out more about this, and the process of drilling the tunnel, in the exhibition.

One of the most remarkable things about the Crossrail project is the speed and efficiency with which the archaeology has been recorded, analysed, published and now exhibited. The final bits of on-site archaeological recording were only finished early in 2016, so it is amazing that in February 2017 we are opening an exhibition showcasing the results of all the work that was done.

This has been an incredible project on many levels – the time span of the material found, the length of the project, the sheer numbers involved (over 200 archaeologists worked on it and tens of thousands of artefacts found), but also the time-tabling and supervision of such an immense project. The Museum of London Docklands is thrilled to be able to display the findings of this programme of work and to be able to highlight the skill and dedication of those who have been involved in it.

The Tunnel: the Archaeology of Crossrail exhibition closed in September 2017.

Love tunnels under London? Want to get updates about the city's past straight to your inbox? Sign up for our free Archaeology newsletter.