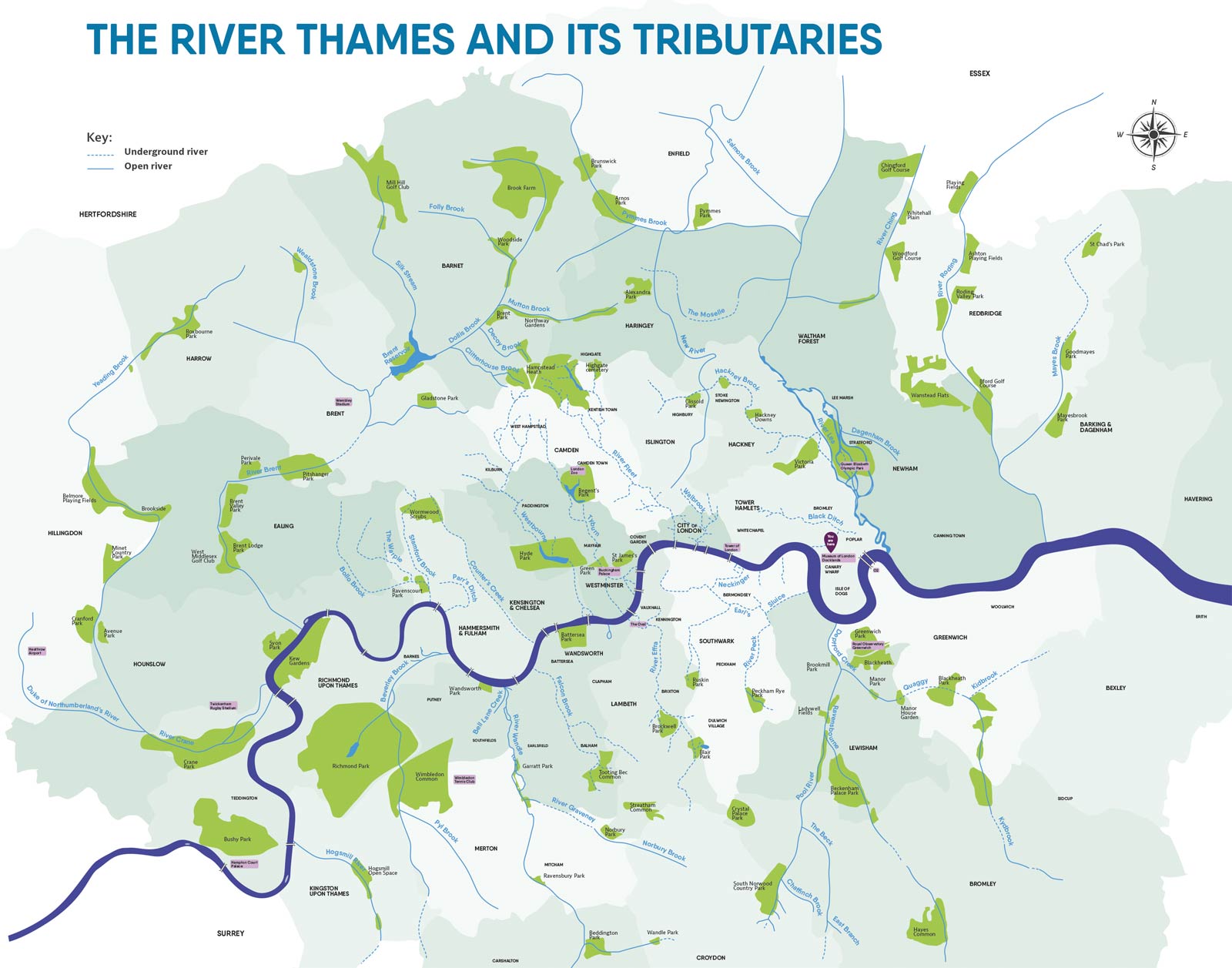

Our 2019 exhibition Secret Rivers at the Museum of London Docklands uncovered the liquid history flowing beneath our feet. We asked its curators how they put the lost rivers of London on public show.

Curators Kate Sumnall and Tom Ardill

With a selection of objects on display in Secret Rivers

What is Secret Rivers about?

Tom Ardill: Secret Rivers is an exhibition about the rivers, streams and brooks that flow into the Thames. Many of these have been buried beneath the streets and become hidden from view. Others remain above the surface, but still have many secrets to reveal.

Kate Sumnall: The exhibition combines our art and archaeology collections to reveal the rich and long history of London’s rivers. We explore themes such as the sacred nature of rivers, how they have been used and abused, modern efforts to improve the rivers and their power to inspire art, music and literature.

What inspired you to create this exhibition?

Tom: In recent years there has been a growing interest in London’s ‘lost rivers’, with books outlining their histories, walking tours tracing their hidden paths through the city, and countless newspaper, magazine and blog articles providing curious facts. Contemporary artists and writers, drawn to the mysteries of these hidden rivers, have sought to reinscribe them into our mental map of the city and create new watery mythologies for London.

Kate: Recent archaeological excavations and research have provided new interpretations for the wealth of material and artefacts that has been found in the river valleys. Cross-referencing the archaeological evidence with contemporary accounts, artistic representations and literature have provided new insights into the relationships Londoners had with their waterways.

Environmental concerns about pollution in the seas and rivers are growing and there is an increasing awareness about how we deal with our rubbish and sewage. It was a good time to take a long view through history and also highlight some of the many local efforts to improve the health of the rivers.

Tom: We realised that the time was right to mount the first major exhibition about London’s secret rivers. We wanted to do something that no other museum could do. Our aim was to use the full range of our collections, along with some loans and new commissions, to really bring the stories to life.

In order to encompass the many roles played by rivers in London’s history, we settled on a thematic approach, taking individual rivers or pairs of rivers as case studies.

What do these rivers tell us about London’s history?

Tom and Kate: In order to understand the long history of London, you need to consider its rivers. The city is here because of the Thames and the many smaller rivers, streams and brooks that flow into it. The Romans established Londinium near the crossing point where London Bridge now stands, and the city grew up along the banks of the Walbrook. It has continued to grow around (and finally on top of) these arteries of the city.

Even before Roman occupation, human activity in the area was centred on the waterways, which offered natural resources and played an important spiritual role. Those resources were heavily exploited by subsequent Londoners. Many of the rivers became incredibly polluted and were used as open sewers, spreading disease.The best solution seemed to be to bury some of the rivers and the creation of Bazalgette’s pioneering sewer system. That story is still continuing as the new sewer infrastructure is built; work continues to open up some stretches of buried rivers and the open rivers are cleaned up.

There are still many clues to the whereabouts of London’s ‘lost rivers’, for example in street names and the layout of roads and buildings. Once you know about London’s rivers, you will never see London quite the same way again.

A conservator works to restore a triple toilet seat found in the River Fleet

Which is your favourite of the featured rivers? What does it reveal about London?

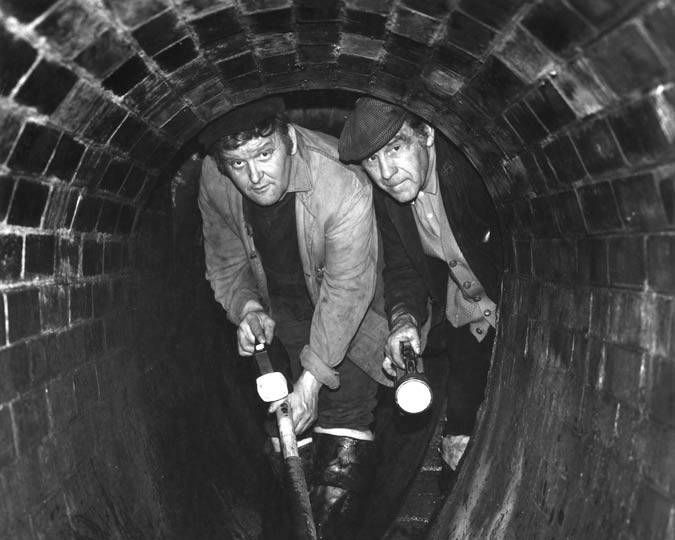

Tom: I am very drawn to the Fleet because it is the largest of London’s rivers to go underground. When you consider that boats once sailed up to Holborn Bridge and that people used to bath in the river by St Pancras Old Church, it is really astonishing that it can no longer be seen. Yet the river’s subterranean existence is also quite tangible as it flows beneath the streets all the way from Hampstead to Blackfriars. If you stand on Holborn Viaduct you can really see the river valley. When the Museum of London moves to its new home at West Smithfield, the Fleet will be just feet away from our galleries in the basement of the former General Market building.

Kate: I really love the Walbrook, a fairly small river but it had a massive impact on London as we know it today. To the Roman army it was an important part of the decision to make the first camp here. Then as Londinium was founded the Walbrook was part of the everyday fabric of the city but was also sacred, a direct link to the gods.

The medieval population of London made the decision to bury the Walbrook. Even underground it continued to exert considerable influence informing the boundaries dividing the administrative controls of the city. These boundaries continue today.

The Walbrook has also provided us with some of the earliest archaeological discoveries leading to interesting medieval theories about early London. The riverine conditions have ensured that important archaeological remains have survived and give a rare insight into the development of our capital city.

This small, buried stream permeates into modern consciousness by inspiring artists such as Adam Dant and Amy Sharrocks. It may be buried but it is definitely not forgotten.

What about what have you most enjoyed about creating the exhibition?

Kate: I have loved creating Secret Rivers, the rivers are fascinating and have given us a very interesting lens through which to study our collections and also the history of London. Researching this exhibition we have met so many lovely people from diverse backgrounds: hydrologists, authors, archaeologists, cartographers, activists and people who strive to improve the health of the rivers. They are all passionate about the rivers and they have inspired us to include so many different strands in this exhibition.

Tom: One of the most rewarding aspects of working on Secret Rivers was to collaborate with Kate and learn about archaeology. We spent many hours going through the Museum of London’s archaeological archive to find artefacts that would tell stories about Londoners’ interactions with rivers. It was a thrill to be able to handle brooches tossed into the Walbrook by Romans, and the medieval wicker fish trap that somebody presumable abandoned or forgot to retrieve from the Fleet. Using archaeology alongside art, photography, textile, ceramics, film and sound enables us to cover 5000 years of river history from Neolithic axe heads to contemporary digital art.

Secret Rivers at the Museum of London Docklands closed 27 October 2019.