In the ongoing saga of the Whitechapel Fatberg, we’ve now acquired our samples of fatberg to add them to the museum’s permanent collection. What does that mean? Where is fatberg now? Is the world safe from fatberg? We asked Andy Holbrook, Collections Care Manager at the Museum of London.

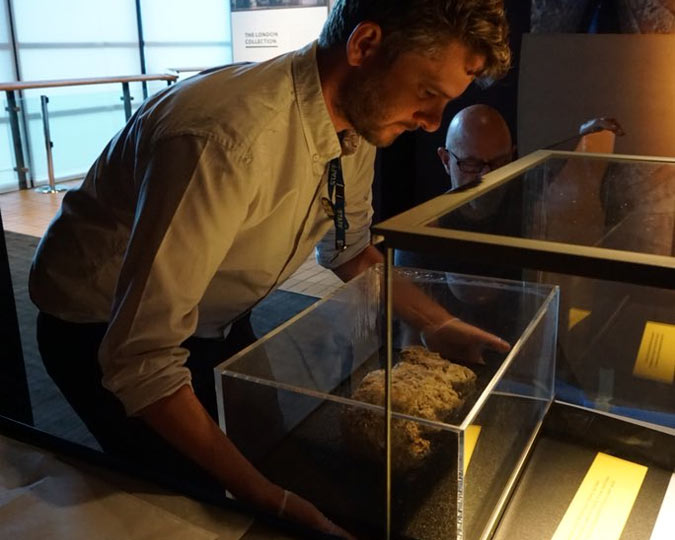

Andy Holbrook removes the sealed case containing the fatberg from display

What is a Collections Care Manager?

Collections care is about the risk management of collections: I work alongside our conservators, but rather than working item by item to clean and restore objects, I make sure we keep them in good conditions. That means keeping the environment at the right levels of heat, light and humidity, as well as preventing pest infestations.

My team also handle the risks in the collections: asbestos-containing objects, our firearms and drugs collections, radioactive materials, and any sort of heavy metals or nasty chemicals. So I became the fatberg wrangler.

What does a fatberg wrangler do?

I’m the only person in the museum who has handled our Fatberg samples outside of their display case- while I was wearing a respirator, a Tyvek suit, googles and gloves. At times you could smell the fatberg despite wearing full face protection. It had a whiff of the festival toilet- something chemical plus people’s contributions to the sewer system.

The fatberg samples were lighter than they looked, it felt a little bit like pumice stone, but crumbly in texture. But Fatberg has evolved since it’s been on display.

What’s the current status of Fatberg?

I saw it when we first acquired it a year ago, in October 2017. Then, it was much darker, it was waxy and wet as it had just been dug up from the sewer. Now it’s much lighter, with a bone-like colour and the texture has become like soap.

We have now formally acquired the Fatberg, so it will now remain in the Museum of London’s permanent collection. Acquiring an object requires a commitment to care for it in the long term, to preserve it for future generations of Londoners. That’s not such a challenge for most of our collections, but nobody knows how to preserve a fatberg. It’s the only object in our collection that has a camera trained on it, 24/7, so we can see how it’s changing in real time.

How are we protecting the world from Fatberg?

The Fatberg is now in our quarantine store, at our Archaeological store in Mortimer Wheeler House. Quarantine is where we keep objects that are toxic, hazardous, or pest-infested. For example, we have a freezer in there which we use for on any objects that might contain parasites or vermin, to kill them before they can infest the rest of our collections.

Fatberg is isolated because it continues to be a hazardous object, and we need to very carefully limit how much we expose our members of staff to it. It’s in a well-sealed showcase, very similar to how we displayed it in our galleries- you can’t touch it and you can’t breathe in the air around it.

I’m one of the lucky ones who continues to go into quarantine and see the Fatberg on a regular basis. Every couple of weeks I go to see if it has physically changed, changed colour, if it is growing any new mould or fungus. The Fatberg went from being displayed in a gallery which was warmer and drier to a slightly colder and more humid environment which activated the spores on the surface.

How are we protecting the Fatberg?

We’re learning from the other objects in our collections. Archaeological leather, for instance, is also prone to mould growth- a lot of our organic materials like wood and even our textiles can suffer. It’s most dangerous for organic materials which the mould can feed off. Mould spores are everywhere, they’re on everything – the conditions where they start growing are where you have no air circulation and high humidity, so we control both those in our collection stores.

The Fatberg is basically a big lump of food for mould spores- full of energy-rich oils. It also came from an entirely contaminated environment: a wet sewer, high humidity, a dirty place full of mould spores and bacteria.

So how are you keeping fatberg from deteriorating?

The approach we took with fatberg was very simple: we explored pickling it, freezing it, freeze-drying it, but made the decision just to air-dry it. That stopped it seeping contaminated liquid, which was the main risk factor to our museum guests. We air-dried it slowly over a couple of months, working with Thames Water and the Lanes Group and that’s the method we’ve continued with. As it gets drier it becomes more stable.

Why are people so obsessed with fatberg?

Part of it is that whole idea of hidden worlds- what happens under our feet. It’s also been one of those really unique objects that combines the highbrow and the lowbrow- what goes on in the toilet is hilarious to British people. Then the highbrow issues about how our diets are changing, and the pressures on the infrastructure of our growing city. Talking about Fatberg enables us to talk about the future of the city.

What next for fatberg?

Fatcam will remain trained on the fatberg for the foreseeable future. We’re hoping to do some more scientific analysis of our fatberg samples, working with Cranfield University to look at how it is chemically changing over time. We were interested in the fatberg’s composition, to help us to tell the story of what it was composed of and how it was formed. That chemical analysis will help our decision making about how to look after it.

We’re now the most experienced museum in the world for curating fatbergs. We’ve been approached by other city museums across the world, asking how they would go about collecting and displaying their own fatbergs. Perhaps we'll take our toxic lump of sewage on an international tour!

Enjoy the festive fun of Fatberg with our Christmas-themed song "12 Days of Fatberg", as sung by the London Gay Men's Chorus.