We explore the street culture of Victorian London, and the almost vanished world of print shops that let ordinary Londoners keep up with the news.

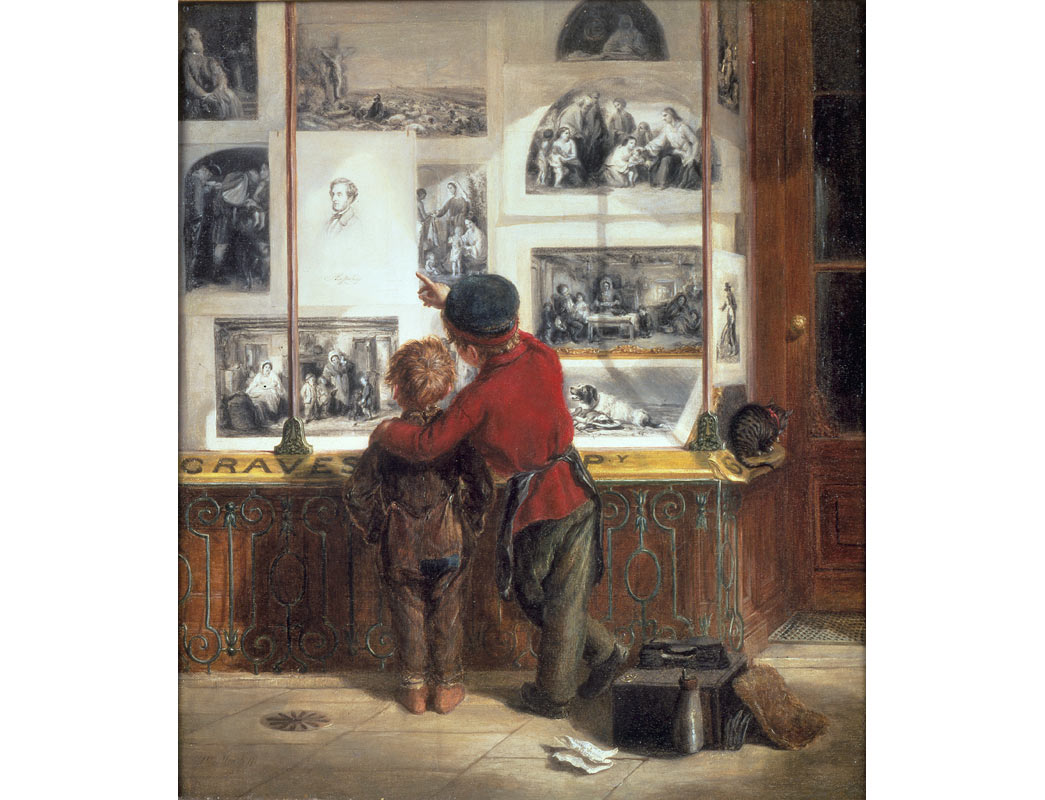

This painting, Lost or Found by Scottish artist William Macduff, depicts a print shop, Graves and Co., with a shoe-black and another young boy staring into the window. The shoe-black is pointing at a portrait of the philanthropist Anthony Ashley Cooper (7th Earl of Shaftesbury) and a selection of prints relating to the theme of charity. It's the centrepiece of the Museum of London’s new Show Space display, A window on Victorian art and charity. The display builds on the theme of this painting with objects and artworks relating both to the charities that Lord Shaftesbury supported and to the London tradition of displays in print-shop windows.

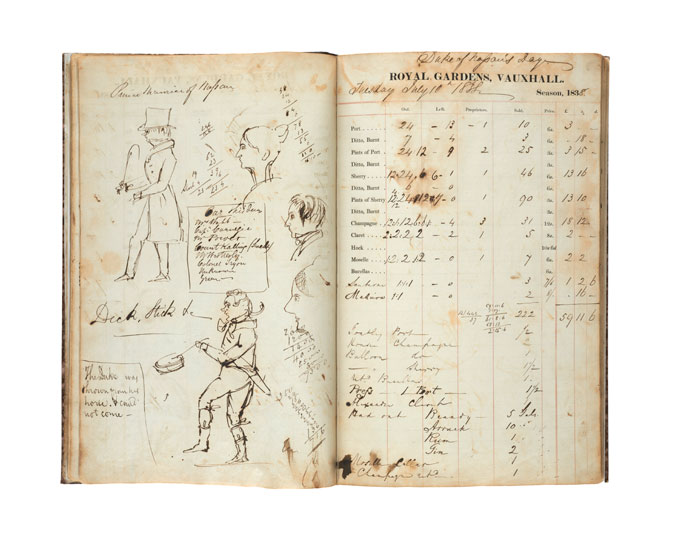

Unidentified owner of a print shop: c.1820

ID no. A15653

London’s print shops were important sites of display in the eighteenth and nineteenth-century city. While many Londoners, like the ragged children in Macduff’s painting, could never afford to buy such fancy printed images, they could view them in the carefully arranged, frequently updated window displays. Some shops specialised in satire, providing a running commentary on current events, fashionable people and contemporary trends. Others – like Graves – dealt in reproductions of paintings by old masters and contemporary artists.

While ownership of these products remained somewhat exclusive in this period, print-shop window displays ensured that they were nevertheless widely seen, going some way towards democratising visual culture in this period. In this age of mass media, images of the world are delivered directly to the home or pocket, and the print shop window has lost much of its novelty, vitality and purpose.

Nevertheless the potential for spectacle, comedy and drama that comes with staring into shop windows retains an appeal. Hollywood action movies frequently feature panicked citizens watching alien invasions unfold through the windows of TV shops, the Christmas displays of London’s most famous department stores continue to be annual attractions, and artists like Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas and Michael Landy have made innovative use of shops to sell, display and, in Landy's case, destroy their works of art.

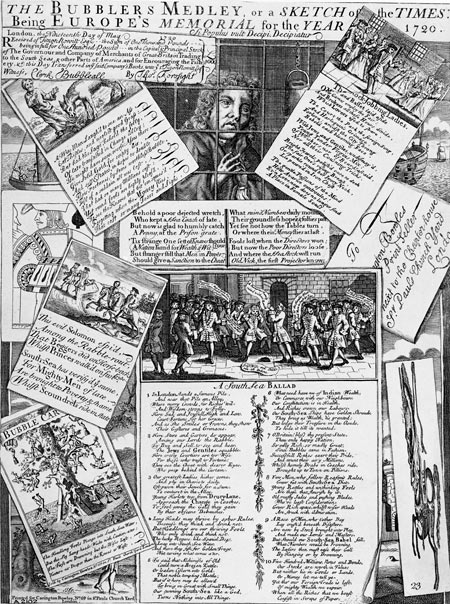

The Bubbler's Medley or a Sketch of the Times being Europe's Memorial of the Year 1720

Printed by Thomas Bowles. Broadside mocking unwise investors in South Sea Company shares & the wickedness of the company's directors.

Macduff’s depiction of Graves and Co. at no.6 Pall Mall does

more than carefully replicate the appearance of a print-shop window. By

reproducing a range of images celebrating charitable acts, hard work and

redemption, the artist developed a nuanced argument about the challenges and

benefits of helping the poor.

This technique of imitating the appearance of a selection of printed images in order to tell a story may have its origin in the ‘medley prints’ of the early eighteenth century. This example, published by Carrington Bowles, satirises the stock collapse of the South Sea Company in 1720 through a poem and a series of images relating to stocks and shares, financial speculation, ruin and imprisonment, all of which are laid out to give the appearance of scatted scraps of paper. It also includes a wrapper addressed to ‘Carrington Bowles Print Seller’ as a crafty advertisement.

Spectators at a Print-Shop in St.Paul's Church Yard, 1774

Print by John Raphael Smith, published by Carrington Bowles. Collection British Museum.

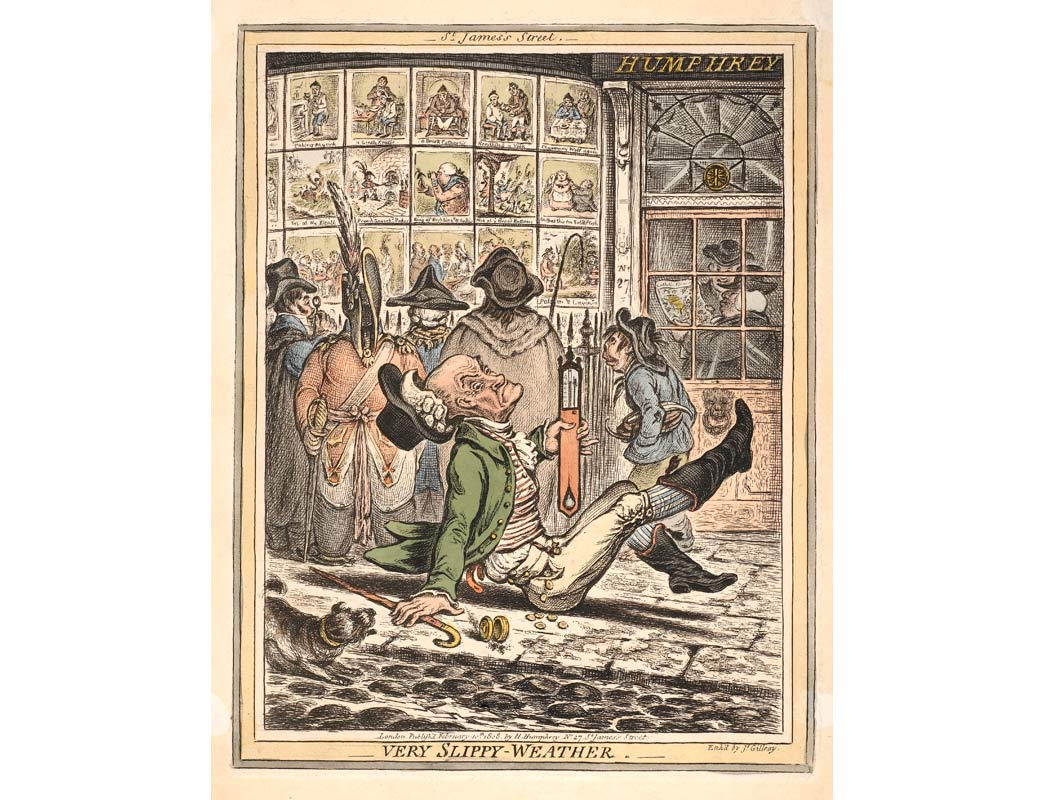

Carrington, and his father John Bowles, went on to produce several engravings depicting the windows of their shops filled with prints. As well as alerting potential customers to their available stock, these images represent people standing outside the premises inspecting the pictures on show. Invariably these people are the butt of the satirist’s joke. Sometimes, as in Spectators at a Print-Shop in St. Paul's Church Yard, they mirror the caricatures on display in the window. In other works, like James Gillray’s Very Slippy Weather, a crowd outside Humphrey’s shop in St James are so intrigued by a selection of Gillray prints that they miss the live comedy taking place behind them as an elderly man loses his footing on the slippery street.

While the subject and composition of Lost and Found clearly derives from this satirical tradition, Macduff’s picture contains no comic imagery and gives us no reason to laugh at the little shoe-black and his companion. Instead, it is a rather sentimental image of brotherly affection with a clear moral lesson. The prints in the window form a visual sermon on the duties and benefits of Christian teaching, philanthropy and hard work. By reimagining print-shop imagery in this way, the artist has set about reforming the genre to make it suitable for his purposes of promoting the philanthropic work of Lord Shaftesbury. By doing so, he has also set about reforming the reputation of the print shop itself. Instead of popular culture, low humour and lewd behaviour, we have high art, self-education and moral purpose. By attaching such attributes to Graves and Co., Macduff was reassuring his audience that a visit to no.6 Pall Mall was a respectable activity, well-suited to the self-improving instincts of the Victorian middleclass.

The subject of people looking into shop windows continued to fascinate artists into the twentieth century. In this newsreel from British Pathé, illustrator Leo Dowd drew these two women looking into the window of a department store in 1946. There is no attempt to create a moral narrative out of the scene; rather Dowd’s concern was to record the fleeting appearance of life on London’s streets. Nevertheless, his decision to draw people window shopping could be seen as celebrating the return to normal life after the end of the Second World War, and is thus as revealing of the spirit of his age as Macduff’s highly contrived composition.

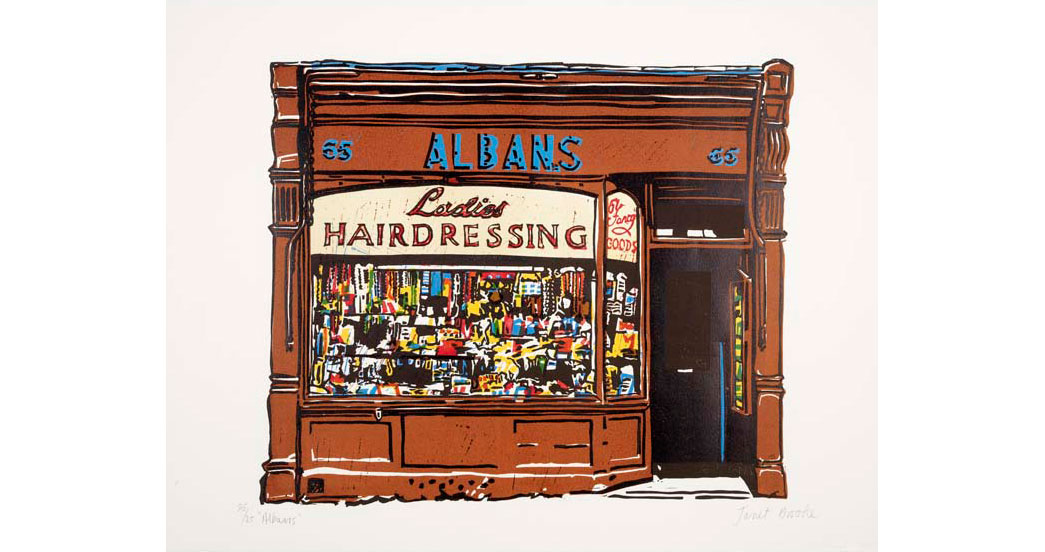

In contrast to Leo Dowd, and indeed all of the artists whose works are included in this display, Janet Brooke is not interested in the novelty of newly-displayed stock or the activity of window shopping. In fact her series of eight linocuts of east London shopfronts do not include any figures, giving them a mournful quality despite the vibrancy of their colours. The artist, who lived in east London in the 1980s, was keen to document the appearance of these traditional independent businesses before they were replaced by chains and supermarkets. When these works entered the Museum of London’s collection she commented that the depicted shops had ‘all now gone in the name of progress’. One of them – Albans Ladies Hairdressing – a long established business on Globe Road in Bethnal Green, shut down in the late 1980s to be replaced by a commercial art gallery, specialising in paintings and prints of London subject matter.

There are many more images of shop windows in the Museum of London’s photography collection, which can be explored on our collections pages.