On the 13th of June 2018 a six metre tall helium-filled, inflatable, angry orange baby version of Donald Trump flew above thousands of demonstrators at Parliament Square in London. They were gathered to protest against the then US president Trump’s visit and his policies.

The Baby Trump (or Trump Blimp) was an instant success, becoming a symbol of British humour and protest against the ‘politics of hate’. The Baby Trump went on to make many more appearances around the world, and several copies were made. Now that the real Trump has left the White House there is less need for the angry baby version to attend protests and it is instead joining the Museum of London’s collections. The Trump Baby was designed by Matt Bonner, and funded by a crowdfunding campaign led by Leo Murray. It was constructed by Imagine Inflatables in Leicestershire. A group of Trump Babysitters looked after it during flight and in transit between appearances.

Trump Baby flying over Parliament square

Photo by Andy Aitchison. Copyright Andy Aitchison

The Museum of London first announced that it was interested in the Trump Baby for its collection shortly after it was flown in 2018. As Conservators caring for the collection we had some initial discussions about the preservation of inflatables, thought about what it might be made from, mused about how unstable some plastic can be and decided that it would be very complicated to display. While the Trump baby toured the world we put the problem to one side, but we did not forget about it, and we were delighted when we were able to finally put the Trump Baby into our quarantine store (appropriately) in the middle of January 2021. Now we just needed to come up with that preservation plan.

Material: What is it made from?

The first and very important thing we as conservators want to know about an object is: What is it made from? The answer to this question will influence how we look after objects: an artwork printed on paper will have one type of storage and display (low light and mid-range relative humidity) and a lead token another (low relative humidity and as much light as you want). Plastics are not quite so clear cut and their needs can vary according to the specific polymer. As conservators we study the deterioration of materials, and we find plastics fascinating because they are such a varied group of materials that can deteriorate in very different ways.

We contacted Imagine Inflatables who made the Baby Blimp and their director Louise Tocca told us that:

“(..) this item is made from 0.18mm PVC material, full surface print. Single layer construction to minimise weight of product and therefore maximise buoyancy.”

It has been printed directly onto the PVC and heat-welded together to create the beautiful rotund shape.

What is PVC and how does it deteriorate?

PVC is an acronym for poly (vinyl chloride), which is a polymer that has been around for a surprisingly long time. PVC was first polymerised in 1872, however industrial scale production required much experimentation and wasn’t successful until the late 1930s. The Second World War accelerated the development of PVC due to increased demand for alternatives to materials such as rubber which were increasingly scarce due to import restrictions.

PVC has been used to produce many different types of object so is found in a variety of museum collections. At the Museum of London, PVC objects are already present in the Dress and Textile collection (shoes, handbags and accessories), and the Social History collection (carrier bags, cardholders, toys, electronics and homewares). The Trump Blimp is the largest PVC object in the museum’s collection, and the first true inflatable, both posing interesting challenges for Conservators responsible for displaying and slowing degradation of the object.

The PVC polymer and the plasticiser that comprise an object such as the Trump Blimp are both susceptible to degradation. Over time the plasticiser will move, or ‘migrate’, to the surface of the object creating a sticky, glossy appearance and sometimes droplets of plasticiser form on the surface. Dust and dirt can adhere to this tacky layer causing the object to become disfigured. The liquid plasticiser at the surface will slowly evaporate meaning that the overall plasticiser content will gradually be depleted. Loss of plasticiser will lead to the Blimp shrinking and becoming more brittle.

PVC handbag with sticky, glossy plasticiser at the surface and dust adhered

Photograph by Abby Moore

The more plasticiser that is lost from the plastic formulation, the more vulnerable the PVC polymer becomes to chemical degradation reactions. Exposure to heat, light and oxygen are drivers for these complex reactions which result in the evolution of hydrogen chloride. If the hydrogen chloride is not removed from the environment surrounding the object, it will trigger further chemical degradation reactions and the process starts to drive itself, or become ‘autocatalytic’. Objects degrading in this way tend to become discoloured and very brittle. If the Trump Blimp degrades in such a way and embrittles in its deflated state, it could become very difficult to display in a meaningful way. One may say that the Trump Baby is self-destructive.

To slow the degradation of plasticised PVC objects, Conservators therefore focus on slowing the loss of plasticiser. We do this by avoiding use of absorbent packing materials that may stick to the surface. We use acid free tissue for a lot of things in conservation, but never for PVC. Slowing air movement over the surface is also important so we will be avoiding storage in well-ventilated environments, or those with circulating air. Reducing the temperature can also dramatically slow chemical degradation reactions, however freezing PVC objects can introduce new risks such as possible shrinkage or physical distortion, condensation formation, and embrittlement which can make handling trickier. Ideally we’d pack it small, without too many sharp creases, layered with non-stick materials in a fridge without any air circulation.

In order to study the composition of the plastic used to create the Blimp in more detail, we will be working with the COMPLEX team- a team of Heritage Scientists specialising in the degradation of plastics, based at UCL’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage. It may be possible to model the Blimp’s degradation under different storage and display conditions to help inform conservation decisions, or carry out aging experiments on similar PVC samples to help us understand how much deterioration we can tolerate before the Blimp becomes unusable.

How do you display a giant inflatable?

The Trump Baby arrived at the Museum in a suitcase. It packs up quite small when it is not filled with air, but it looks nothing like the Trump Baby as we know and love it. In order to display it in its full glory it has to be inflated. Having it sitting in a corner like a deflated beach toy would not do justice to the original intent of its creators.

The Trump Baby was filled with helium when it flew over parliament square. Helium is a colourless, inert, non-toxic, monatomic gas that is used in balloons because it is lighter than air. If the Museum of London wants to display the Blimp outside hovering in the air this is the gas of choice. However, launching a giant balloon in central London is complicated. When it flew over Parliament square, which is considered restricted airspace, it had permission from the Greater London Authority, Metropolitan Police and National Air Traffic Service. In order to fly in the City of London it would need additional permission from the Lord Mayor’s office. When previously airborne the Trump Baby was flown for a few hours only, for the duration of the protest or demonstration.

Helium is an expensive gas, it is also a finite natural resource, and inflating and deflating the Blimp with Helium every day would take a lot of resources (monetary, natural and human). Keeping it inflated for longer periods will also be an issue as there is likely to be some seepage of the gas through the PVC. PVC is porous, and any gas will slowly migrate out. The typical kid’s helium balloons have a metallic layer in the plastic, this is what stops the gas permeating through the surface and thus they stay inflated for longer. The Trump Baby does not have a metallic layer, and just like an ordinary air-filled balloon slowly deflates, so will the Blimp.

The weather is also an issue if it is inflated outside- it will need to be taken down in winds stronger than 15mph. Pollution in the air will deposit on the surface, dirt, frequent cleaning and high energy Ultra Violet light from the sun are also likely to speed up deterioration of the PVC. So it’s possible to display it floating outside, but it may be best for only short periods on a wind-still evening after the sun has gone down.

What about inside? Using Helium gas in large quantities inside is not possible as it can pose Health and Safety risks- if released it can act as an asphyxiant in an enclosed space. The next question is therefore - can we fill it with compressed air? We asked Imagine Inflatables, they confirmed that it can indeed be filled with air and suspended. The air will permeate slowly through the PVC (like helium), so it will need to be topped up on a regular basis. Given its size we need to investigate options for inflation (fans or pumps) and we will need to monitor and test how often it needs topping up. The Blimp has only one chamber for air and is filled from one area, a ‘sock’ in the back bum area. We will need to investigate what pressure it needs, and be careful not to overfill it as that might put undue pressure on the PVC fabric and lead to damage.

Inflating the Blimp is likely to create a flow of air through the PVC material (inside to outside). The inflated Blimp will also be on open display in the galleries which are served by an air conditioning system that actively circulates the air. Increased air flow will encourage plasticiser loss and ultimately hasten deterioration of the material. Heat is also a factor in the deterioration of the PVC and display conditions are likely to be warmer on gallery than the museum’s collection stores. Because hot air rises and the ducting and outlets for the heating system are positioned high up, Trump’s head, which is 6m above the floor, is likely to be quite a lot hotter than his feet. Light levels are also a consideration, and this will inevitably cause some change to the material. A decision about how long to inflate and display the Blimp for will therefore need to be a careful balance of access and long-term preservation.

Staff will need training in inflating and deflating the Trump Baby. Companies experienced in launching blimps, like Imagine Inflatables, can give us training in how to inflate and deflate it safely. It is a complex operation to inflate the Trump Blimp, whether inside or outside, with helium or air, and that is something we, as Museum of London conservators, have not had any experience with. The only inflated objects on display in our Museum are the tyres of cars and bikes. We pump these up on a regular basis, as the air permeates through the rubber tubes.

We will need to secure the Baby up or down, it has integrated tethering points on the front and back shoulder blades, around the diaper, and at the top of the head. To prevent stretching and deformation we will need to use all the tethering points, to spread the weight evenly, whether we are tying it down or suspending it from above.

Only the head is inflated, note the tethering points on the shoulders

Photo by Andy Aitchison. Copyright Andy Aitchison

Some people have a strong dislike for anything criticizing the former president of the United States. The Trump Baby is a controversial object; a smaller version, flown in Parliament square in June 2019, was stabbed. Another Trump Blimp was slashed in Alabama in November the same year. If we are to display it at the Museum of London we must make sure that it is safe, so we will need to discuss security options and barriers with our experienced security staff. Normally when we display something very fragile in the Museum we put it in a showcase. That is obviously not an option for the Trump Baby. A positive thing is that it is designed to be viewed from a distance, so it will not necessarily impact on the viewers experience if we limit how close visitors can get. Incidentally when flown in Parliament Square it had a soft safety cordon around it manned by the Trump Babysitters.

What does the future hold?

The Trump Blimp throws up a lot of interesting ethical problems for conservators and curators:

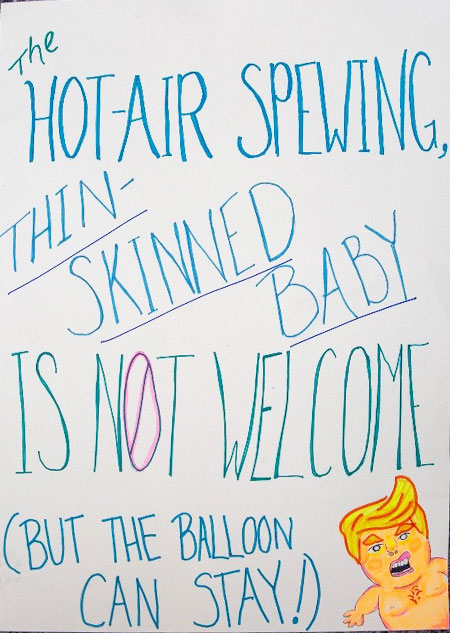

It may not last forever but the Balloon can stay. Placard from the June 2018 protest

Photo by Andy Aitchison. Copyright Andy Aitchison

- Should we display it floating, as originally intended? Is filling it with helium part of the original ‘intent’ of the object?

- Should we display the Blimp for longer whilst Trumps presidency is still fresh in people’s minds, or should it be displayed for a short period and the emphasis put on preserving for future generations?

- Should we make the most of it whilst we can; or risk it deteriorating slowly in storage? Will it still be in a meaningful condition in 50+ years? Will inflation be possible in 10, 20 or 30 years?

- Could we inflate it once, and ensure we document/ film it? (footage already exist of it being flown during protests.) Can we show just the film or do people want to see ‘the real thing’.

- Is it possible to show it deflated? Or do people have to see it inflated for it to be impactful?

- Will scientific modelling of plasticiser loss give us an indication us how many times it can be deflated and how long for before it reaches the end of its useful life?

In a hundred years if the PVC has deteriorated the balloon no longer holds air, and the current conservators have been replaced many times over it may have to be displayed deflated, mounted in some way to show its full size, or maybe filled with something that makes it hold its inflated shape, reminding the future of a few tumultuous and eventful years, the little bit of history we are all living in right now.

Thank you:

- Trump Babysitters

- Louise Tocca, director, Imagine Inflatables

- Andy Aitchison for letting us use his wonderful photos

- Wikipedia