Let's explore the radical work of photographers Neil Kenlock and Armet Francis. Second in our series on documenting the changing lives of black Londoners.

In 2019, our Curating London project moved into the borough of North Kensington. We were collecting contemporary objects, images and stories to record how Londoners live in the 21st century. In North Kensington, the Museum of London collaborated with local youth arts collective FerArts to explore the rich history and identity of this culturally diverse area of London. To mark the occasion, and commemorate Black History Month, we’ve delved into our collections to highlight the work of photographers who documented North Kensington’s black British community, from Charlie Phillips to Roger Mayne.

Neil Kenlock and Armet Francis were two radical figures, who took their cameras onto the streets of North Kensington as part of a wider commitment to documenting the lives of African-Caribbean people across London and beyond. Both Jamaican-born, Francis and Kenlock arrived in Britain as children and became well-established professional photographers.

Kenlock launched his career through advertising and editorial photography, before finding himself at the forefront of black British history and culture. He was the official photographer of the British Black Panther movement in the UK during the late 1960s and 1970s, a press photographer for the West Indian World newspaper, and the co-founder of ROOT lifestyle magazine and Choice FM radio station, both pioneering media outlets catering specifically to a black British audience. From a young age, Kenlock said he realised “there was discrimination and I needed to fight that. I thought everybody should be equal, that things should be fair. There was a way to do that [through photography] without disregarding my own culture.”

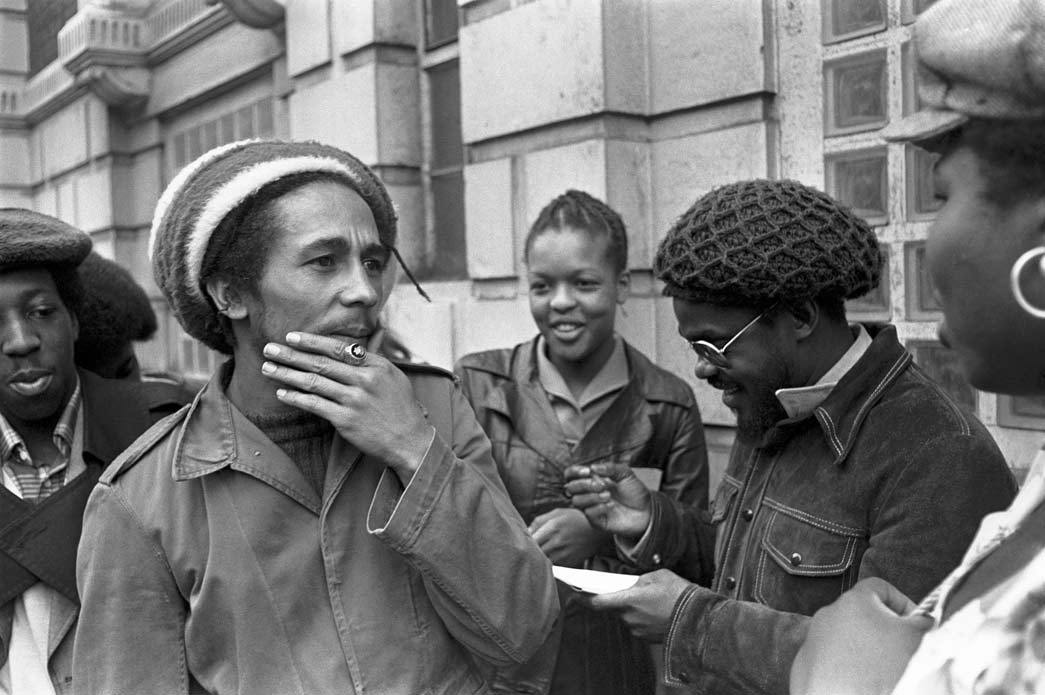

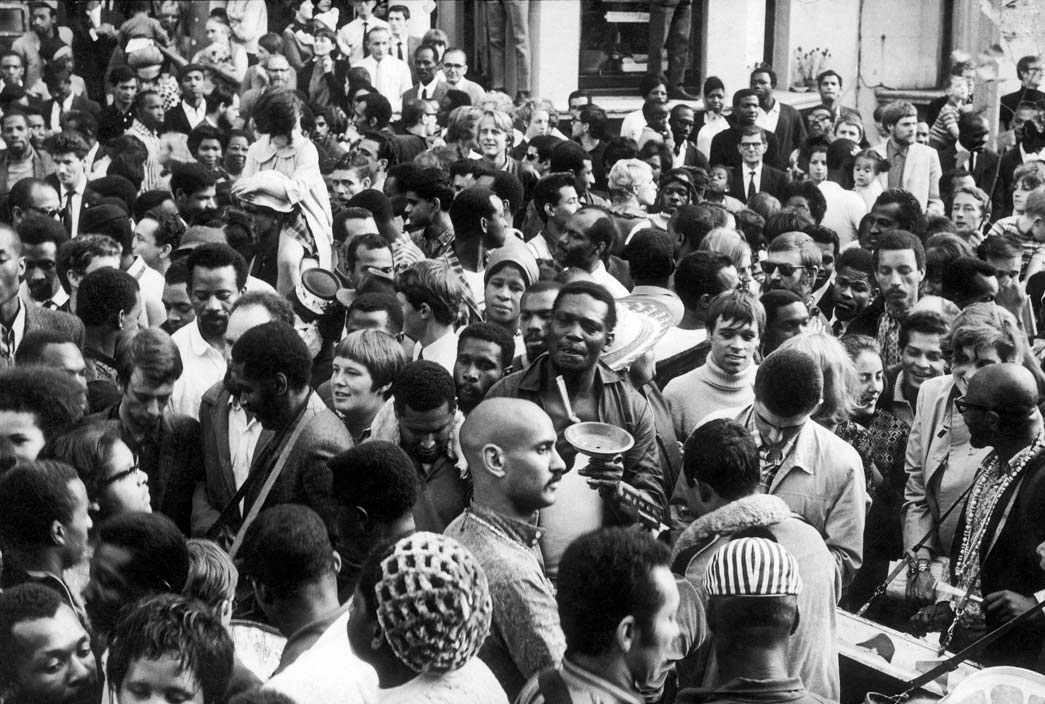

Black Panther demonstration, London, 1970

Neil Kenlock

As a result of his involvement with the British Black Panthers, Kenlock extensively photographed demonstrations and anti-racism protests in London. He portrayed numerous political and historical figures, including civil rights activists Olive Morris, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Darcus Howe, and international celebrities such as Muhammed Ali, Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, and Marvin Gaye. With his powerful, incisive portraits, he sought to represent people who had long been invisible or stereotypically portrayed in public discourse, giving them a voice that had up to then rarely been heard. “Black people never had any personality, any strength, always looking down,” he later reflected. “That’s not what I wanted my subjects to look like.”

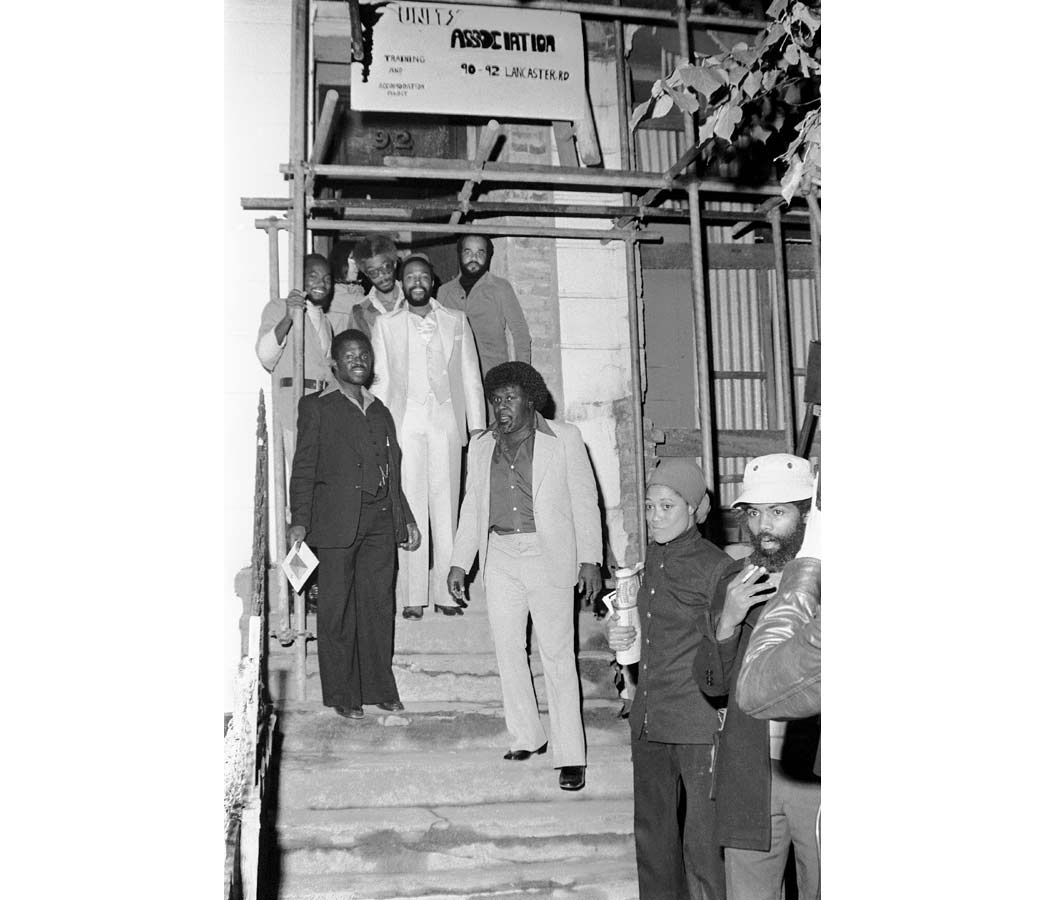

Neil Kenlock

A South Londoner like Kenlock, Armet Francis became a fashion and advertising photographer in London after a difficult youth in Elephant & Castle. Having come to Britain from the Santa Cruz Mountains in Jamaica, Francis experienced a profound sense of dislocation as a schoolboy: “England changed me from a smiling little boy into the resilient person I am now. There were a lot of bullies. I had to defend myself everyday. I had to learn their ways of being. The things that made me different were the things I got rid of first.”

The shock of arriving in Britain made a long-lasting impact, especially when Francis realised that most Jamaican migrants were unable to go back to their hometowns. The reality they faced in their new environment in London was harsh and unrelenting: “They didn’t have enough money. They walked into serious racism. They couldn’t even get anywhere to live. They came into a frozen urban jungle, into some serious racism.”

Francis had come to photography from an unusual direction. He suffered from an eye condition that forced him to give up the active lifestyle he had originally pursued as a marine cadet and to choose a completely different profession instead. The practice of photography turned out to put the least strain on his eyes. He initially learned the trade as an assistant in a commercial photography studio, going out on commissions to shoot holiday camps, room sets and food. He started working in the booming business of fashion photography in the 1960s. The fashion business was a predominantly white environment and Francis was at first little exposed to the social changes that were pushing ahead the struggle for civil rights. “I realised this is what it’s about now, the Civil Rights movement, the Rastafarian movement. There was no history of black photographers in England. I decided to do black images, to capture how black people perform in a certain vernacular, with certain experiences and history with all its social and political implications.”

Francis’ newfound concern with black British identity in the 1960s shifted his focus in photography as he embarked on two lifelong projects – The Black Triangle: People of the African Diaspora and Children of the Black Triangle – that explore black diasporic communities in Britain, Africa and the Caribbean. Francis subsequently became the first black photographer to have a solo exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery in 1983 and in 1988 he co-founded Autograph ABP (previously known as Association of Black Photographers), which continues to promote the work of artists who deal with issues of identity, representation, rights and justice.

Neil Kenlock, Armet Francis and Charlie Phillips each made significant contributions to British photography, and their pictures capture a post-war moment during which London underwent radical social changes. Their work was shown in our 2005 exhibition Roots to Reckoning: the photography of Armet Francis, Neil Kenlock and Charlie Phillips, after which the museum acquired 90 of their photographs. They still count among the key highlights in our collection. Today, these images continue to help us reflect critically on the unfinished history of racial discrimination and injustice in British society, and to challenge and remake dominant historical and visual narratives.