For International Cat Day, we thought we'd delve into our collections to find historical evidence of cats living in London. How have we treated, or mistreated, our feline friends in ages past?

Do you have a cat in the city? Share a picture with us using #LondonView.

English tin-glazed jug, c.1670

Decorated with blue and yellow alternating lines to simulate hair.

Cats have lived side-by-side with humans since before the city of London was built, first being domesticated in the Middle East about 9000 years ago. Our collections are filled with images and representations of cats - and sometimes, the historical cats themselves. This jug for example, is from about 1670. Novelty jugs in the shape of cats were popular in Stuart London, particularly to serve cream or milk.

The famous London diarist Samuel Pepys mentions cats in his account of everyday life in 17th century London, including being woken at 1am by his yowling housecat, and an extraordinary sight after the Great Fire of 1666:

"I also did see a poor cat taken out of a hole in the chimney, joyning to the wall of the Exchange; with, the hair all burned off the body, and yet alive."

This is the taxidermised body of a cat named Oliver, who was owned by a family in Charlton around the end of the 19th century. Oliver is preserved in a seated position, with a yellow ribbon around its neck and glass eyes. Alongside him are a small silver slipper and the remains of a floral bouquet, now badly decomposed. We don't know exactly what they signified, but they're very suggestive of a wedding. Perhaps Oliver was a wedding present. He was clearly a beloved pet, and is an interesting example of the changing status of domestic cats during the Victorian period.

Only recently have many cats been fed, cherished, or kept indoors. For much of the 19th century cats were kept primarily to eradicate vermin. They were frequently ill-fed and mistreated, and there were many strays in the streets of London. Cats were also widely used for scientific experimentation, until they became the subject of anti-vivisection campaigns at the end of the 19th century. Towards the end of the 19th century, cats began to be kept more widely as family pets and companions, particularly amongst the fashionable middle classes. Oliver is an example of this growing trend in pet-keeping.

A less well-preserved example from our collection, the mummified body of this cat and rat were found behind some bottles at the London Docks in the 1890s. Cats were allowed to run freely around the busy warehouses that lined the Thames, to try and control the vermin that feasted on the goods within. These working cats were expected to earn their keep, and some London businesses even put their resident mousers on the payroll (like the Post Office, which allowed one shilling per week for working cats in its Money Order Office, to supplement their catch).

Dead cats are sometimes found behind walls in old house, and this isn't the only mummified moggy in the museum's collection. Traditionally, it was thought that cats warded off evil spirits, and some may have been deliberately entombed when houses were built, to protect the future inhabitants. Another theory is that dead cats were placed there to frighten off vermin such as mice. No doubt a number of cats, like this one, were either walled up by accident or chased their prey into inescapable spaces.

Cat & dogs' meat shop, 1935

Bishops Bridge Road, Paddington. © Wolf Suschitzky

Here's another sign of the changing status of cats, from working scavengers to pampered pets. From the mid 1800s, "cat's meat men" wandered the streets of London, hawking food for cats and dogs door to door. They sold mostly horse meat, rendered down from the hundreds of horses slaughtered in the metropolis every week, once they were too old or sick to work. These feline provisioners bulked out their product with meat too old or diseased to sell to humans, selling it for about 2 and a half pence/lb (about £1.29/lb in 2017 value).

Victorian social researcher Henry Mayhew estimated there were 1000 cat's meat sellers in London in 1861, serving about 300,000 cats, one for every house (allowing for multiple cats in some homes, plus strays). Each cats's meat seller walked a particular route serving a few hundred households, their approach marked by mewling cats who knew it meant dinner time.

The first commercial cat food was sold in London from 1860 by American entrepreneur James Spratt. His "Spratt's Patent Cat Food" was filled, according to the company's many advertisements, with nourishing "meat fibrine" sourced from North American buffalo. However, cat's meat sellers remained a common sight in London into the 20th century, both street hawkers and better-off vendors who could open their own shops.

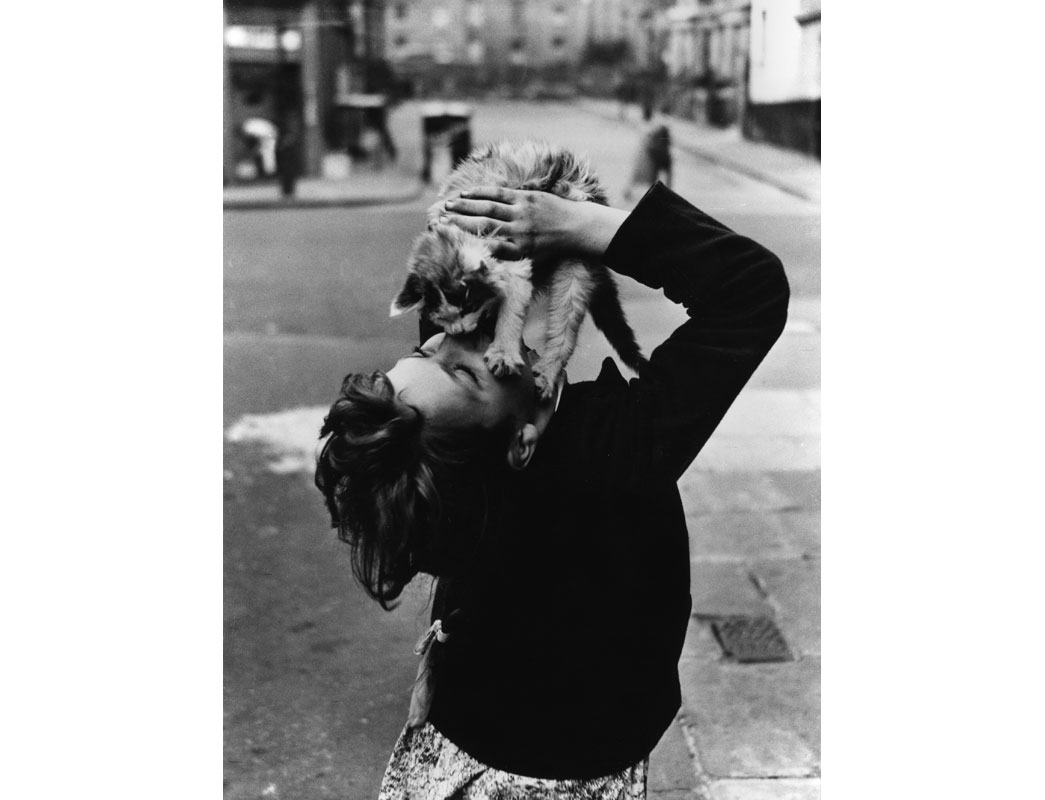

A boy rubs noses with a dog he holds in his hands. A cat is also zipped up underneath his jacket, Brick Lane

1980. © Paul Trevor. All rights reserved.

As the 20th century went on, Londoners became ever more cat-crazy, even as the city shrank and the industries that had once employed professional mousers declined.

As of 2016, about 12% of households have cats, for a total of 580,000 domestic cats in the metropolis (the average cat owner has 1.4 cats, which sounds uncomfortable for the fractional feline). Interestingly, there are about 340,000 dogs, which is the same 2:1 ratio that Victorian researchers observed in the customers of cat's meat sellers. London is also the region with the lowest cat ownership of any in the UK, which isn't surprising with a city with so many rented flats and little garden access.

Votes for cats

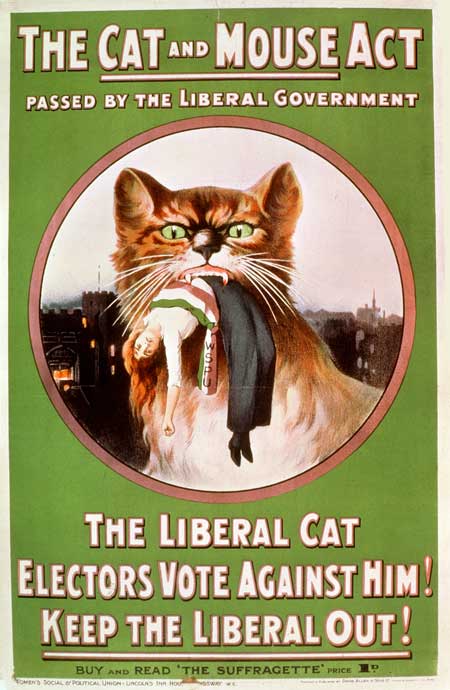

The Cat and Mouse Act poster, 1914

Opposing the 1913 Prisoner's Temporary Discharge (for Ill Health) Act.

Being slightly less literal, our collections are filled with images of cats. All of these examples come from the time of the suffrage movement, the campaign aimed at securing women's right to vote from about 1900-18. However, both of the postcards above, which look rather sweet to modern eyes (at least mine) were designed to mock the suffragette movement, suggesting that giving women the vote was as absurd as letting cats vote in elections.

The "Advokate for Women's Rights" is wearing traditional suffragette colours of green, purple and white. The postcard with a kitten mewing "I want my vote!" was sent, anonymously, to Christabel Pankhurst, the prominent women's rights campaigner, in October 1908. It's a reminder that harassment of prominent women in politics predates the internet era.

This poster, created by the women's suffrage movement, denounces the "Cat and Mouse Act". This refers to the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge (for Ill Health) Act passed by the Liberal government in 1913. The act allowed imprisoned suffragettes who used hunger striking to protest to be released temporarily, only to be re-imprisoned once they had recovered. It was this technique of "Letting them go, only to catch them again" that suffragettes denounced as cruel - as cruel in fact as a cat playing with its prey. This fierce, almost sabre-tooted cat is an interesting contrast to the cuddly anti-suffragette kittens.