A graveyard, uncovered in London during the 1970s, offered both a huge opportunity and a terrific challenge for archaeologists, who had to excavate over two hundred bodies before the bulldozers rolled in. Lucy Creighton investigates what stories these bones have to tell, nearly 1000 years on.

The 2016 Delivering the Past display explored the history beneath the site of the former General Post Office near Newgate Street, a stone’s throw away from the Museum of London. We uncovered more than 3000 years of human history, from prehistory to the Second World War, but let's focus on the Londoners of the 11th & 12th centuries.

Archaeologists excavating the site of the General Post Office in 1974 came face to face with these medieval Londoners when the remains of 234 people were discovered. These were bodies from the graveyard of St. Nicholas Shambles. This small parish church was built in the early 11th century and expanded several times before it was demolished in 1552. The graves all date to the 11th and 12th centuries.

This

graveyard is really significant as it was the first to be excavated on a large

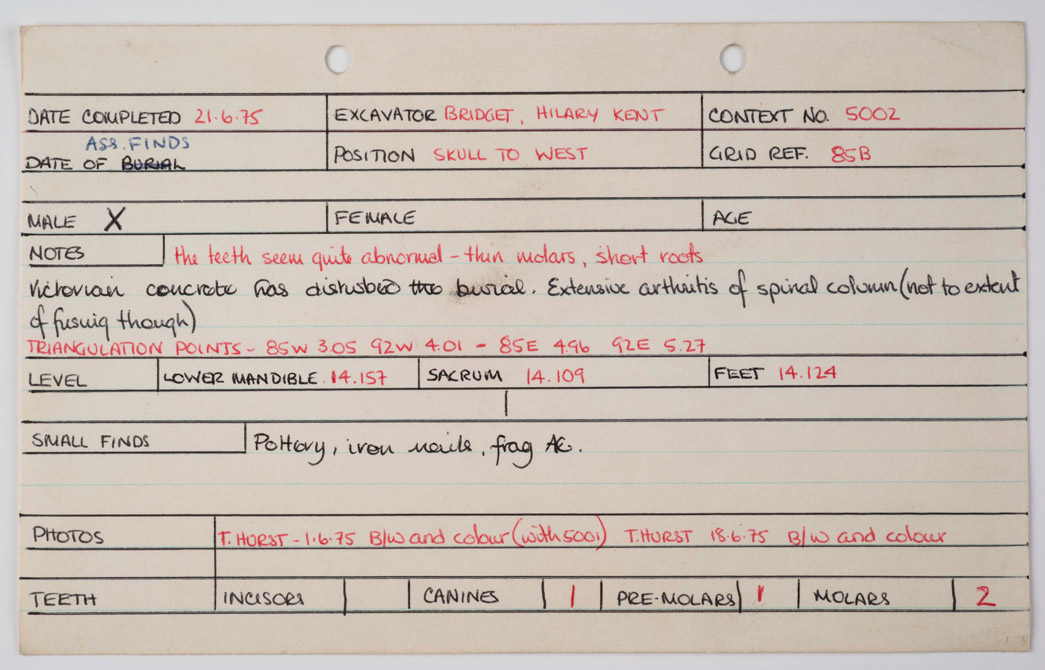

scale within the City of London, and under significant time pressure. The General Post Office site was destined to be the home of the new BT Centre, and there was only a limited time to investigate and record the ground before construction was scheduled to begin. For this 'development-led' archaeology, diggers had to quickly develop new

ways of recording the mass graves in sufficient detail. Recording sheets specifically for skeletons

were developed. These standardised how archaeologists working across the site

were describing and recording what they found, allowing for better comparisons

to be made later on.

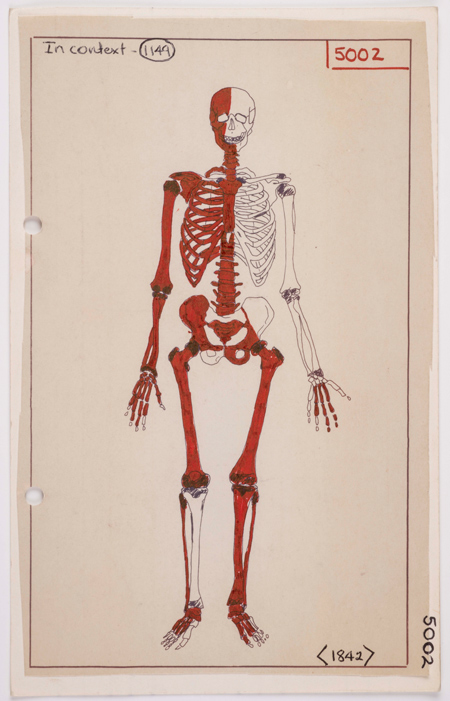

The front of a skeleton recording card

Indicating which bones were found in each grave; ID no. GPO75_5002_3b

Non-archaeological tools, such as spoons and paint brushes, were used to delicately excavate the skeletons and the bones were cleaned before photographs of the whole graves were taken. The contents of each grave needs to be carefully recorded by archaeologists so that they can be compared and interpreted after the excavation is complete. Photography on site allowed the time-consuming process of drawing each grave to be done at a later date. Nifty ways of lifting and bagging the bones saved time during lab analysis. The vertebrae were strung in order before lifting and the left and right side of the body was bagged separately, as were the small bones of the hands and feet.

Archaeologists were able to establish that the people at St. Nicholas Shambles were buried in five different ways. The vast majority were buried simply, with nails, fragments of wood and scraps of cloth suggesting they were wrapped in shrouds within wooden coffins, most of which has rotted away. Some of the deceased were given stone pillows or placed in stone-lined chambers. Others were laid on floors of crushed chalk and mortar, possibly to soak up oozing bodily fluids produced during the process of decay. In just one case – the burial of a child – charcoal was used to line the grave and was placed on top of the body. These varying ways of burying offer us tantalising insights into the beliefs of the deceased and the funeral ceremonies that their loved ones carried out.

We can get closer still to the lives of people by looking at the human remains themselves. Detailed examination by osteoarchaeologists, who study excavated human bones, provides insights into the health of the population. Teeth can tell us so much about people’s health. As could perhaps be expected from a medieval cemetery, lots of people (75% of adults to be precise) had calculus on their teeth, a form of hard plaque caused by a lack of scrubbing. This sometimes led to the development of chronic gum disease, causing teeth to loosen in the jaw. We can tell that people buried in this cemetery were affected by calculus as most individuals had several missing teeth, despite the fact that tooth decay and abscesses were far less common.

Some remains even tell us about the circumstances surrounding the deaths of individuals. This small fragment of cranium gives us an insight into a violent event that happened more than 800 years ago. As you can see, this individual – a man aged 17-25 years – has received a nasty blow to the head. The shape of the wound suggests a sword. The position of the blow tells us that the unfortunate individual was attacked from behind and the angle of the cut suggests the attacker was right-handed. Amazingly this wound may not have proved immediately fatal, as the blade did not cut through the full thickness of the bone. However, as we can’t see any signs of the bone around the break healing, the victim probably didn’t survive for very long after the attack. Until 16 December 2016, you can get a closer look at this skull fragment, which will be one of a selection of artefacts available to handle in connection with the Delivering the Past display. This sort of detective work with excavated human remains can reveal fascinating insights into the way Londoners have lived – and died – for thousands of years.

To learn more about the human remains held at the Museum of London, visit the Centre for Human Bioarchaeology.

Want to get updates about the city's buried past straight to your inbox? Sign up for our Archaeology newsletter to find out about upcoming exhibitions, events and articles.