Author Frances Burney was known to support abolition of slavery, and yet she owned a mahogany writing desk that was steeped in the history of slavery. How do we make sense of this contradiction?

Frances Burney, aka Mme d'Arblay, was a prolific writer and playwright. (Courtesy: National Library of France, France)

In 1786, the novelist Frances Burney took up employment at the royal court, as a ‘Keeper of the Robes’ to Queen Charlotte. Burney, whose novels Evelina (1778) and Cecilia (1782), had been published to great public success, accepted the position a means of securing some financial and social independence from her family. Though she found the work tedious, she developed a genuine friendship with the queen and her daughters.

Half a world away, in the West Indies, a very different kind of employment was under way. Across the islands and coastal regions of the Caribbean, mahogany trees were felled by logging gangs of enslaved Africans and indentured labourers, for export to Britain and north America. Originally regarded as a cheap and undesirable hardwood, suitable only for use as ship ballast, by the middle of the 18th century, mahogany was established as the premier wood by the leading cabinetmakers and designers of the day. The deforestation of Jamaica and other islands, caused by mahogany logging, in turn cleared land for the vast sugar plantations that would be the foundation of the West Indian slave economy.

Wood politics

Durable, warm-toned and able to take a high polish, mahogany was the material of choice not only for large items such as cabinets and beds, but also for scientific instruments, dressing cases, tea caddies and other genteel objects. It was to be found in Georgian homes ranging from royal palaces to the neat terraces occupied by London’s merchants and professional classes.

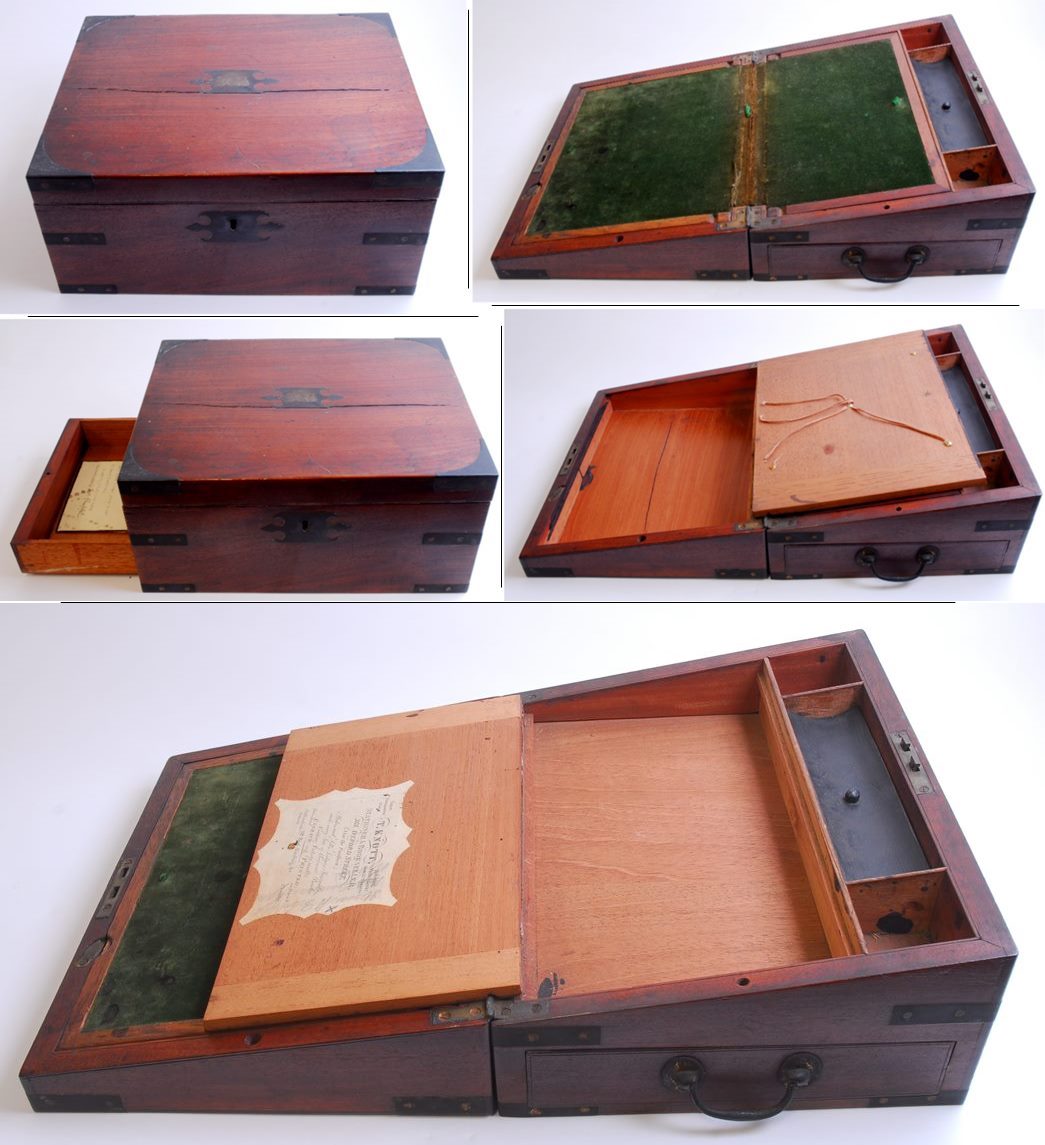

In the Museum of London’s collection there is a mahogany writing box, or portable ‘writing desk’ which was given to Frances Burney by Queen Charlotte. As a prolific diarist and letter-writer, as well as a novelist and playwright, Burney must have spent many hours with this item. Despite its royal origins, it’s a simple and un-showy piece, with no embellishment save for plain brass fixtures — well suited to Burney (whose own taste was for ‘simple elegance’) and likewise to the queen, who was as frugal as her royal status would permit.

The desk’s paper label with the maker’s name is pasted on the underside of the upper lid. (ID no.: 39.168)

Unfolded, the box transforms into a sloped writing surface, lined in dark green velvet, with compartments for holding an inkwell, quill pens and a supply of paper. There is also an integral drawer, in which correspondence could be stored. Underneath one of the compartment lids is a paper label, indicating that the box was made and sold by T. Knott, a stationer and bookseller at 361 Oxford Street, next to the fashionable Pantheon concert hall. On the corner of the label is a small notice: “Mahogany writing desks from 12 shillings upwards”. At the time, 12 shillings constituted the best part of a week’s wages for a skilled labourer or artisan, and a month’s wages for a live-in servant. Simple as it might appear, a box such as this one was a luxury object!

In one sense, there is nothing unusual about someone like Burney owning this box. She was a genteel and educated woman who was paid a salary of £200 per annum by the queen, as well as receiving payment for her writing, and was certainly financially comfortable at this stage of her life. Likewise, she consorted with the most noted cultural celebrities of 18th-century London, and was well aware of what was considered fashionable in design. And yet — Burney, who we know from her letters was in favour of abolishing slavery, owned and used something that was ultimately created from slave labour!

How are we to make sense of this contradiction?

Deep within the woodworks

Contrasting history

The

mahogany ‘Buxton Table’, currently on display at the Museum of London

Docklands. (On loan from the London Borough of Newham, ID no.: L361)

Committed abolitionists began to boycott West Indian sugar in the late 1780s in order to undermine the profits of the slave trade, although this movement did not become widespread for several years. There was no movement to abolish the use of mahogany at the same time — in part, because the centre of mahogany logging had shifted from British-controlled Jamaica, to Spanish-controlled Honduras by this time; albeit still undertaken by enslaved people. Fundamentally, the ripple effect of the slave trade affected virtually every type of economic activity in 18th-century Britain. Even individuals opposed to slavery were liable to consume products that had been produced by the system of enslavement and colonial exploitation, whether directly as raw materials, or indirectly from trade networks and the accumulation of capital.

‘Exotic’ luxuries produced from this system of global exploitation included mahogany, tobacco, cotton, sugar, spices, coffee and indigo dyes; gradually becoming accessible to a broad middle class as the system expanded its reach. Even prominent abolition campaigners were entangled, as the mahogany-veneered ‘Buxton Table’ (on display at the Museum of London Docklands) demonstrates. Originally belonging to the abolitionist MP Thomas Fowell Buxton, it was the table on which Buxton, William Wilberforce and their allies drafted the 1833 bill to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire.

Disturbing parallels

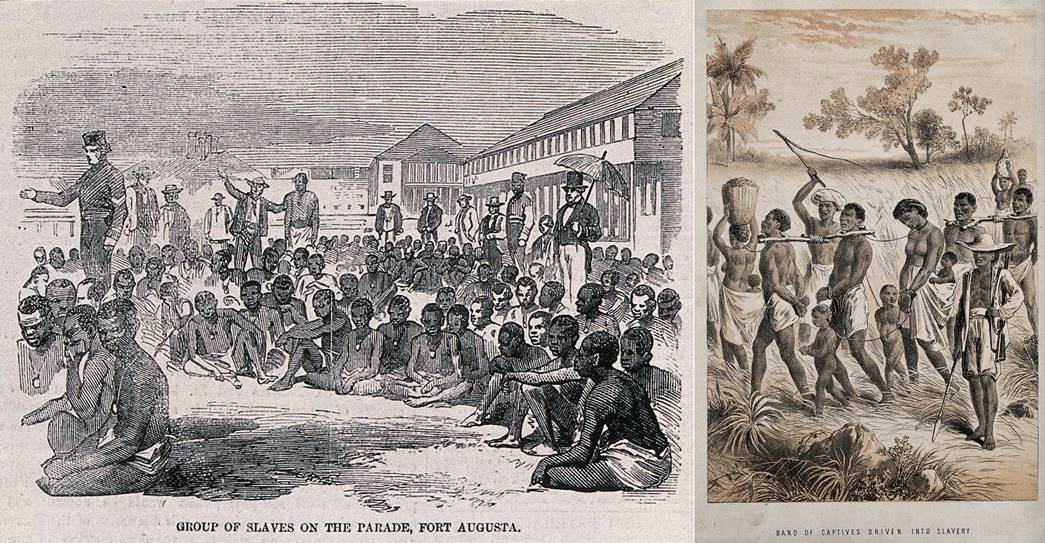

(left) African people rescued from a slave ship by the Royal Navy, brought to Fort Augusta, Jamaica. Wood engraving, 1857 (Courtesy: Wellcom Collection); African men, women and children captured in order to become slaves. Lithograph, 1874. (Courtesy: Wellcom Collection)

While Frances Burney is not remembered as an abolitionist writer, per se, she was well aware of the cruelties of slavery. In her last novel, The Wanderer (1814), the protagonist Juliet is a young white woman who dons blackface as a disguise in order to escape from revolutionary France. The categorisation of racial identity, and the racist hierarchy which privileged whiteness over blackness (and supposedly justified the enslavement of African people), had their origins in 18th-century scientific discourse. As the secret of Juliet’s whiteness is gradually revealed, and she moves ‘up’ the racial hierarchy, the novel’s other characters react in ways which demonstrate the racist and colonial thinking of the time. Once she presents as a white woman, she is eventually perceived as refined and civilised by the same people who wished to reject her as a black woman.

It’s a complex novel, which criticises the hierarchies and categories of race without ever fully breaking away from them. What is apparent, though, are the disturbing parallels between the perception of people of African descent, and the perception of the raw materials grown and harvested by enslaved Africans: rough, uncivilised, rude and raw. Slave-grown sugar had to be refined, and slave-forested mahogany had to be polished, before it could be consumed and enjoyed by refined and polished white Europeans. Contained within an elegant object like Frances Burney’s mahogany writing desk, is a global history of pain and exploitation.

Discover how the trade in enslaved Africans and sugar shaped London in the London, Sugar & Slavery gallery at the Museum of London Docklands. Pre-book your tickets here.