Many major diseases have struck London through its history, from the Black Death that devastated the medieval city, to Spanish Flu, which first struck over 100 years ago. Can we learn from them to fight the epidemics of the future?

May 2020 update: See new Disease X virtual exhibition

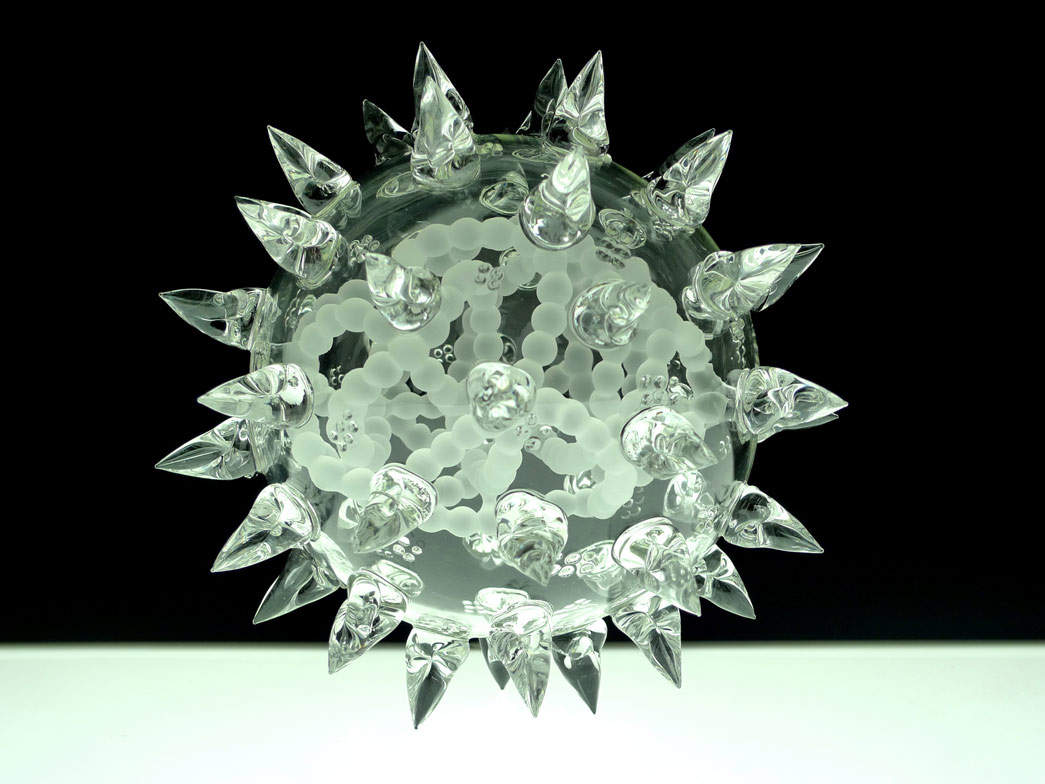

What is Disease X?

Every year the World Health Organisation (WHO) creates a list of ten priority diseases, choosing which of the potential epidemics facing the world most need researching. Alongside such familiar maladies as Ebola and the Zika virus, 2018’s list for the first time warned of “Disease X”.

This hypothetical future disease represents the risk that “a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown”. Disease X stands for all the plagues that are unknown to humanity — until they strike.

"Untitled Future Mutation", 2018. Artwork by Luke Jerram

Representing a possible future pathogen. On display in Disease X.

Vyki: “Nobody knows what might cause Disease X, but London has been hit by numerous epidemics over the centuries. This exhibition is about what we might learn from past to tackle the diseases of the future.”

Roz: “2018 is also the centenary of the Spanish Flu epidemic, that swept the globe in 1918 and 1919. We’re marking that anniversary, and looking at other major plagues to hit the capital.” So what are the lessons to learn from historical epidemics?

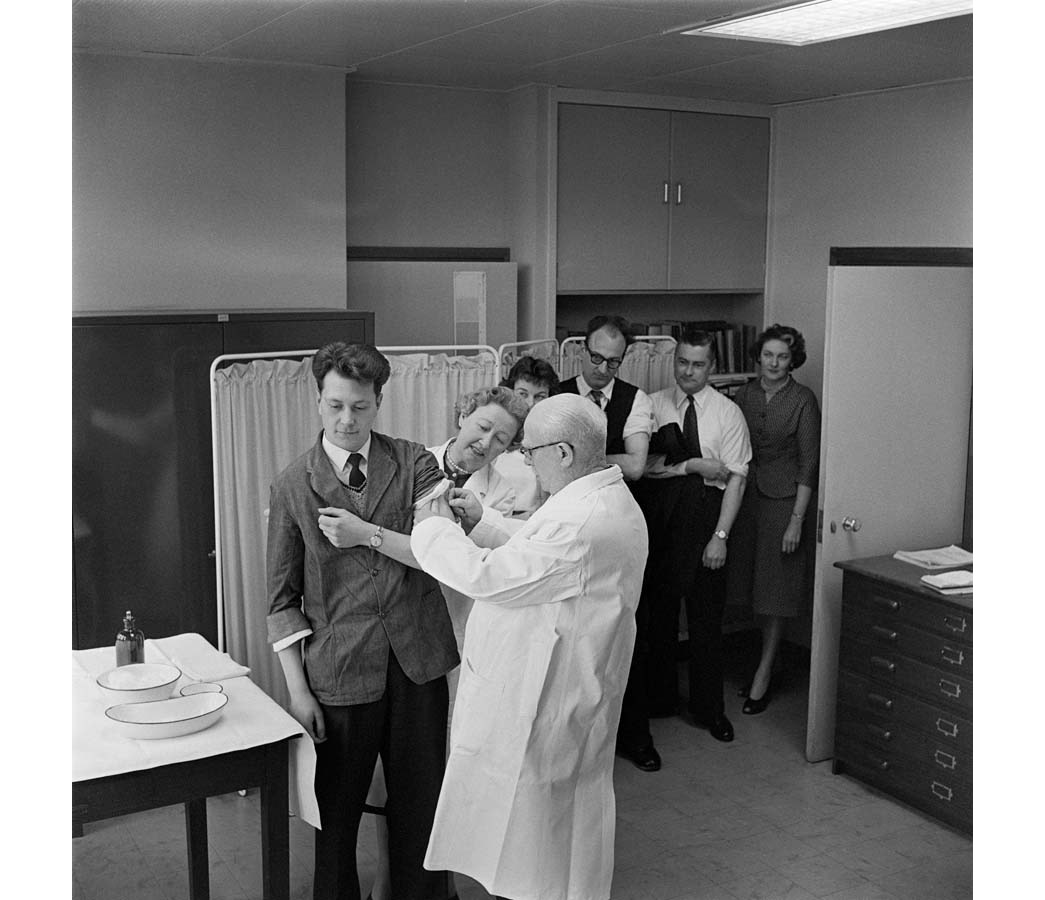

Influenza: understand the threat

Roz: “18,000 Londoners were killed in the 1918-19 influenza epidemic, and 50 million worldwide- more people than died during the First World War.”

Vyki: “We interviewed Dr Edward Wynne-Evans, of Public Health England, who would be one of the experts called upon if an epidemic hits London. Public health advice is vital during an outbreak, to let people know what they can do to stop spreading disease. He says that one key is preparing for the crisis in advance: you can, for example, become an authoritative source on public health information before the epidemic strikes, so you can get your message out quickly and effectively.”

But what do you do when you do not know how to tackle a disease? Medical science was not so advanced when the Spanish Flu struck London in 1918. The concept of the virus was not yet understood. Most people believed that influenza was caused by a bacteria, and scientists hunted in frustration for the bacillus that could explain the disease . The lack of proven remedies allowed unscrupulous people to sell patent remedies, like this Flu-Mal, which claimed to fight both influenza and malaria.

Memorial edition of The Graphic magazine, 1892

Commemorating the death of Prince Albert Victor, who died of Russian Flu

It’s now thought that the 1918 epidemic was a strain of bird flu. Vyki: “We also spoke to Professor John Edmunds at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who studies past outbreaks to improve our understanding of how diseases spread. We have good data going back as far as the Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918-19."

Through statistical analysis, Professor Edmunds has established, for example, that during the 1957 influenza outbreak there was no peak in mortality among those aged over eighty – because that generation had gained immunity by surviving the 1892 outbreak of Russian Flu. It’s believed that these may have been similar strains of the disease.”

That outbreak, also featured in Disease X, provides one of the most arresting objects on display. It’s Queen Victoria’s mourning dress, which she wore during the “Russian Flu” pandemic of 1892. According to one estimate, 25% of Londoners contracted the disease, with thousands dying. Among them was Prince Albert Victor, eldest grandson of Queen Victoria. He died less than a week after his 28th birthday, while planning his wedding to Princess Mary of Teck, who later married his brother George. It’s a reminder that disease can strike anyone, regardless of their status.

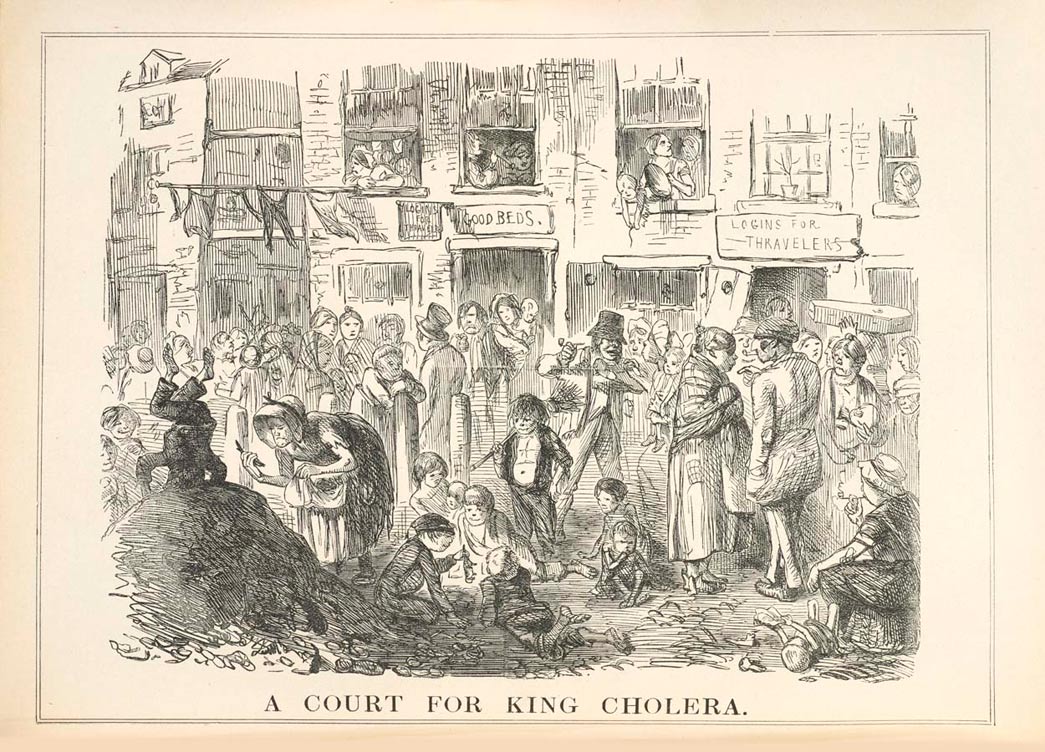

Cholera: know how diseases spread

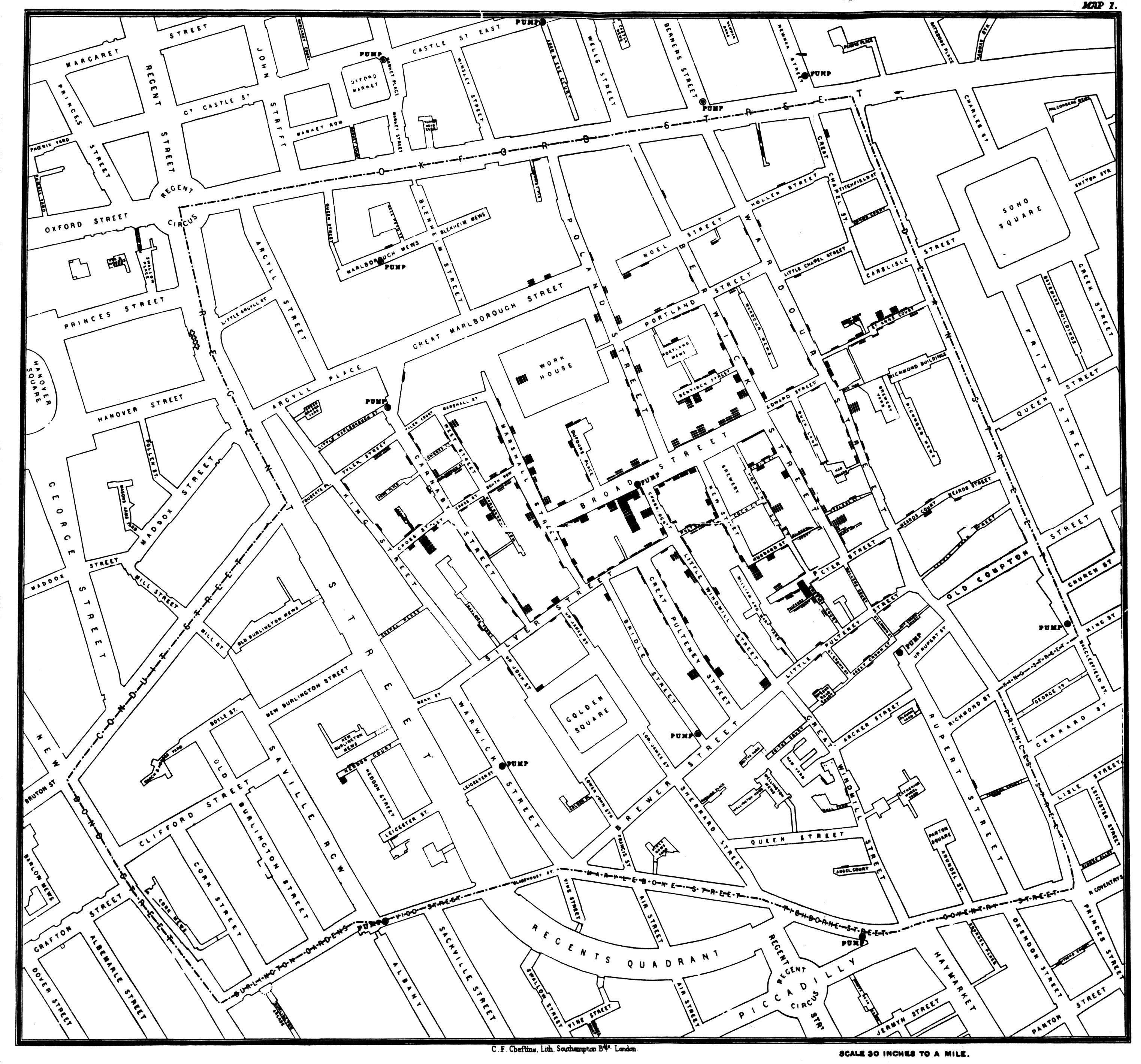

Epidemological map by John Snow showing the clusters of cholera cases (indicated by stacked rectangles) in the London epidemic of 1854

Vyki: “During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, Professor John Edmunds' team provided real-time analysis and predictive models that showed how the disease might spread. Models like these can help inform the authorities’ decision making. Should you, for example, close schools or airports, and which measures might be most effective in stopping transmission."

That modelling would have come in very useful in 1918, when there was little understanding of how to help stop the transmission of influenza. One of the personal stories on display in Disease X was that of artist Mabel Pryde whose son came home on leave from the Western Front in 1918. She felt unwell, but was determined that he should enjoy his leave, so took aspirin so that she could take him to the theatre.

Ill-ventilated and packed theatres could have helped the transmission of air-borne viruses, such as Spanish Flu, but this was not widely understood in this period, even by the public health officials. A few days later Mabel passed away, having succumbed to Spanish Flu. Her son-in-law, the poet Robert Graves, believed her only consolation was that illness had prolonged her son's leave.

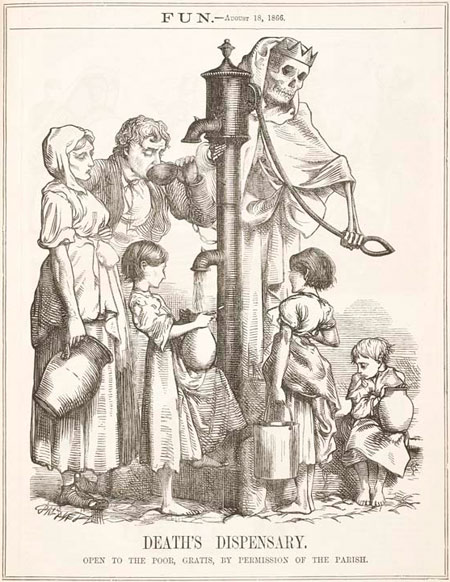

Death's Dispensary, 1866

"Open to the poor gratis, by permission of the parish." From the August edition of Fun magazine.

Roz Sherris: “Sometimes past Londoners saw diseases coming but they didn’t know what to do about them- when cholera struck in the middle of the 19th century, they thought it was spread by miasma- literally “bad air”, that the stink of rubbish made people sick by itself. They didn’t know that the cholera bacteria was carried by contaminated water. It took pioneering work by John Snow ‘the grandfather of epidemiology’, to prove that. He monitored cholera fatalities in the area of a water pump in Broad Street, Soho and found that when the pump handle was removed there was a noticeable decrease in deaths."

Vyki: “Due to Bazalgette’s sewer system, London would be well protected against Disease X if it was water-borne: our water supply is fairly well protected against infection.” But London could still be at risk of an outbreak of Disease X, depending on its transmission method. For example, the sexually transmitted disease HIV/AIDS has taken the lives of 40,000 Londoners since the 1980s.

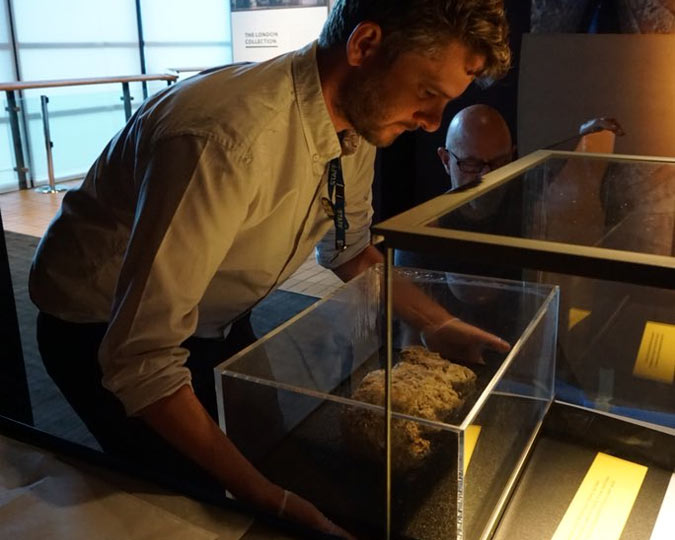

Smallpox & AIDS: diseases can be defeated

The effects of smallpox have left traces on the bones of this child's elbow

Vyki: “One of the most moving objects on display in Disease X are the human remains: an infant who was around 9 months old when they died suffering from smallpox. Despite how sad this case is, it demonstrates something very important: humanity can overcome epidemics.

Smallpox is a success story, because it has been completely eradicated through a world-wide programme of vaccination." Now, no more children or adults will die suffering with smallpox.

Vyki: “The Disease X display includes the pioneering work of

the sexual health clinic 56 Dean Street. They focus on early diagnosis and

treatment, identifying London’s most at-risk groups. As well as immediately issuing

antiretroviral drugs for those newly diagnosed with HIV, they prescribe PrEP, a

drug which can prevent infection. Their work has led to a huge drop in the rate

of new cases of HIV in London. Public Health England think this model might

lead to the end of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Britain - by getting us to a zero

percent rate of transmission, so that the disease is no longer passed on.”

And what other stories would our curators have liked to include in Disease X, but couldn’t squeeze in?

Roz: “We have four stories of people who died in the Spanish Flu outbreak, but we would have loved to include more. In some ways, that epidemic left relatively few traces on history, because it was so fast-acting. They said you could be fine at breakfast and dead by teatime. Compare it to a disease like consumption, where you would spend years languishing, being painted looking pale and interesting.”

Vyki: “I really wish we’d been able to include more material showing the personal impact of the AIDS epidemic- we just don’t have the objects in our collections to tell those stories. We are still actively collecting and if anyone has anything that they think we would be relevant to the story of individual people affected by AIDS, please get in touch.”

Roz: “We want people to leave on a positive note – we can improve things, we can eradicate old maladies and take public health measures to stop new ones. We can fight diseases, but you need to work out what they are first.” Perhaps studying London’s past epidemics will help us stop the future Disease X.

The Museum of London is grateful to all of the contemporary scientists and the Wellcome Trust who helped us to develop this display.

Disease X was on free display at the Museum of London until March 2019.