In January 2019 we displayed artefacts from pandemics in London's past and future. Our star object was an elegant black dress worn by Queen Victoria, in mourning for her grandson, who died in the 1892 'flu epidemic. But how do you safely display a fragile costume that's over a hundred years old?

The Museum of London has many fascinating and iconic objects relating to the British royal family in its collection. Recently I was fortunate enough to work closely on a dress worn by Queen Victoria. The dress has not previously been on display at the museum, so this has been a great opportunity to showcase one of our many objects with royal connections.

Photograph issued for Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee, 1897

Photograph taken by W. Downey, 1893. Public domain.

The dress in question has been dated to 1892. It is believed Victoria wore it in mourning following the death of her grandson Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence, who died during an influenza pandemic. At this point in her life Victoria was in her early 70s, she was also in the fourth decade of mourning her husband Prince Albert, who had died in 1861.

Following Albert’s death, Victoria adopted traditional black mourning wear which she wore for the rest of her life, a look that she is now very well known for. In her later years, Victoria’s height also appears to have decreased slightly from when she was younger, so when she wore this dress she would have stood at approximately 4 feet 8 inches tall.

Close up image showing silk taffeta, mourning crepe and covered buttons

Comprising of a bodice and skirt, the dress is made from black silk taffeta and embellished with layers of black silk mourning crepe. Mourning crepe is a textured open weave silk, specifically worn to indicate to others that the wearer was in a certain stage of mourning. The bodice is lined in fine cream silk, with baleen (whalebone) boning at the waist.

Although most of the seams are machine stitched, the dress has many handstitched elements and shows a high quality of craftsmanship, as you may well expect the Empress of the British Empire at the height of its power to be wearing. These details: the quality and cut of the fabric, the colour, the shape, the size, and texture, all help to build up a picture of the Queen's life at this time.

As a textile conservator, my job is to care for the museum's large collection of fabric objects in order to maximise their longevity and ensure they are available now and in the future for museum visitors. This includes assessing, conserving and mounting objects required for exhibitions. This is always a collaborative process, working alongside other conservators, curators, exhibition designers and technicians.

The dress is in surprisingly good condition, considering its

age combined with silk's inherent tendency to degrade rapidly. This initially suggests that the dress was not worn very

much. However, on closer inspection the tell-tale signs of wear around the

neckline indicate that it is likely to have been worn several times. The

outside of the dress required minimal conservation treatment to prepare it for

display, so my focus moved to the interior, which has several areas of damage.

Although these will not be seen when on display, without appropriate support these

already fragile areas could be weakened during handling, especially with the accumulative strain of being mounted for several months.

The neckline showed the most amount of wear, with several splits and loose areas of braid. We used fine ‘hair’ silk to stitch a colour-matched silk crepeline (sheer woven fabric) overlay into place. I used a very fine curved surgical needle to slide easily through the delicate silk without damaging the weave.

The inner waist ties, which were used to keep the bodice cinched in at the waist, were in poor condition. Several long splits had formed where they had originally been tied and they were fraying along all the edges. As these grosgrain ribbons are densely woven, I selected an adhesive support rather than purely stitched support, to minimise the amount of stitching required. After preparing an adhesive-coated black silk crepeline support, I heat-set patches at a temperature of 70°C onto the splitting areas using a heated spatula and secured the edges with supplementary stitching.

After the dress was conserved the next stage was to mount it

onto a mannequin. This was a challenge not only to create the correct period

silhouette but also in trying to represent such a recognisable historic figure

as accurately as possible.

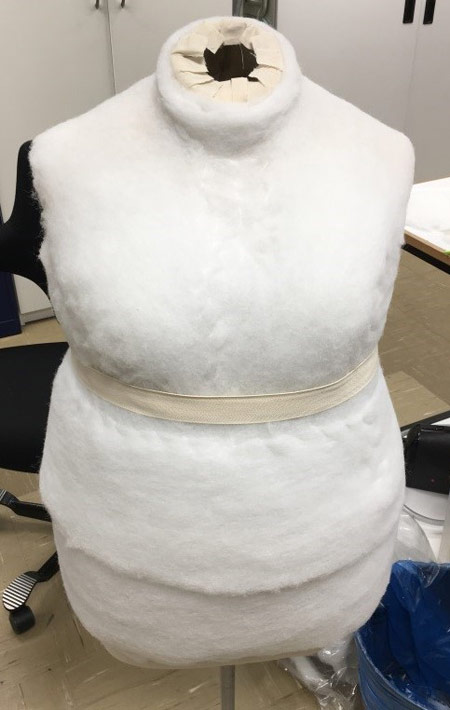

Initial stage of padding with polyester wadding.

Unlike a dressmaker who begins with a figure and then creates a garment to fit, when mounting historic costume the shape of the figure is taken from the garment and the correct figure is built up like a sculpture. By measuring the bodice and skirt, seeing where adjustments had been made, and referring to contemporary photographs of Victoria, I was able to pad up a standard mannequin (UK size 16) to suitable proportions using layers of polyester wadding.

This was firstly pinned into place and then each layer secured with stitching. Some more drastic adjustments also needed to be made by cutting down the long slender neck and adding padding to widen it.

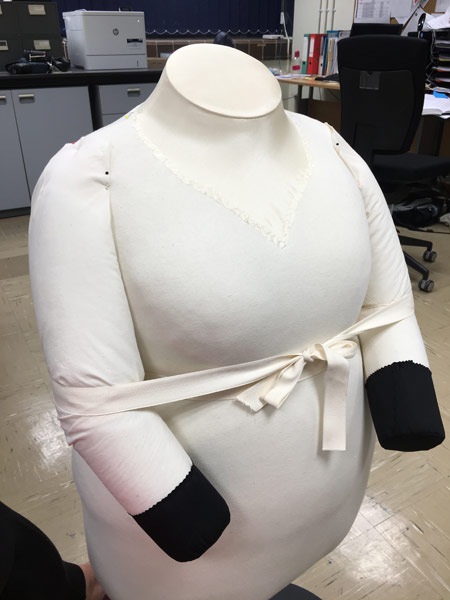

Padded mannequin with silk neck covering and padded arms.

After the padding was in place I made a fitted cotton jersey cover and then padded fabric covered arms using a similar method to the torso. The neck was covered in cream silk habotai, to tie in with the overall exhibition design, and the arm ends were covered in black silk.

Once the torso and arms were complete, I built layers of underpinnings to create the full skirt and bustle which were the fashionable shape of the 1880-90s. Layers of gathered nylon net were built up onto a boned tube skirt, and a boned full length bustle was made to hold up the weight of the silk layers needed for the length of the exhibition. A soft gathered net layer and black silk overskirt were the final layers to provide a smooth surface to easily slide on the skirt.

Once dressed and the skirts carefully arranged, a final light vacuum was needed to remove any fibres or dust from the crisp black silk and then the dress was ready to be installed in the gallery. It took three people to lift the dressed mannequin safely into its display case, while supporting the mannequin and the long skirt train.

Love fashion? Subscribe to our fashion newsletter to read more stories from our collections, and find out about upcoming events and exhibitions.