19 February 2017 marks 300 years since the birth of David Garrick, the actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who introduced a new realistic acting style onto the stage and had a profound influence on all aspects of British theatre.

The Museum of London holds a curious selection of objects across different areas of the collection relating to the life, works and reputation of this London icon. This article puts some of these items into the context of his life and legacy.

Raised in Litchfield, Garrick came to London at the age of twenty with his friend and former school-master Samuel Johnson. He had intended to study law, but the death of his father and a legacy of £1000 from an uncle enabled him and his brother to set up instead as wine merchants. A contract to supply wine to the Bedford Coffee House – a haunt of artists, actors and managers – gained him an introduction into the theatre world, and by March 1741 he was taking roles at Goodman’s Fields Theatre.

Staffordshire pottery model of David Garrick, c. 1840

At first he appeared under a pseudonym, or was billed as ‘A Gentleman’, being concerned about damaging his family name by associating it with the theatre. His early triumph as Richard III, however, encouraged him to go public. Garrick’s fame, and his association with this role, were reinforced with the painting by his friend William Hogarth, depicting him at a highly dramatic moment in the play when the king awakens from a dream on the eve of the Battle of Bosworth. A print was also made after the painting and continued to be published for twenty-five years, indicating the popular demand for the image.

The Museum of London's collection includes not only two copies of the print, but also a tapestry with a design based on the image. This expensive – and somewhat outmoded – item of luxury furniture was presumably commissioned by an early and very wealthy enthusiast. Although the tapestry itself is unique, it attests to the growing ubiquity of Garrick’s image as early as the 1740s. Garrick memorabilia has continued to be made ever since. In the mid-1800s, for example, admirers could buy Staffordshire figures of the actor in this most famous pose. A new statue of Garrick has recently been commissioned by the Garrick Litchfield Theatre to celebrate his tercentenary.

After his success with Richard III, Garrick soon became the principal male actor at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and in 1747 he took over the theatre’s management. In the same year he starred as Ranger alongside Hannah Pritchard’s Clarinda in Dr. Benjamin Hoadly’s comedy, ‘The Suspicious Husband’. Their partnership is captured in a double portrait by Francis Hayman, who was employed as a scene painter at the theatre. Ranger has just discovered that the woman he has been flirting with is in fact his cousin, Clarinda in disguise. Embarrassed by the discovery, he turns to the audience declaring, ‘I must brazen this out’.

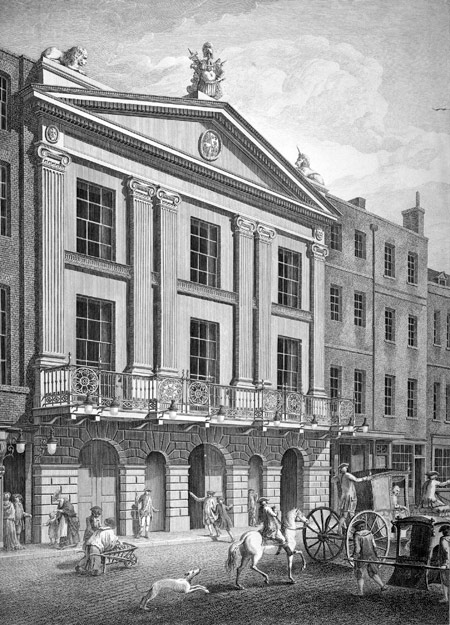

View of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 1776

Engraving by P. Begbie; ID no. C123

Garrick managed the Drury Lane Theatre for 29 years in partnership with James Lacy. Over this period he professionalised and modernised the theatre, winning accolades for his work and transforming its previously declining fortunes. Shortly before he retired in 1775 he was able to commission the Adams brothers to design a grand new entrance, as seen in this print.

During his career, Garrick not only continued to excel in both tragic and comic roles, but also to write and direct plays. He is particularly noted for his role in popularising the works of Shakespeare and bringing his plays to a wide audience. His legacy was felt in making both the theatre and the acting profession more socially acceptable. As Samuel Johnson put it, "his profession made him rich and he made his profession respectable."

Garrick & Hogarth, or the Artist Puzzled, 1845

Satirical 'mechanical print', R. Evan Sly; British Museum collection, BY-NC-SA

Garrick was a favourite of portrait painters, and one of the most frequently depicted men of the eighteenth century, probably painted more often in his lifetime than anyone in Britain except the monarch. Painters were not only attracted to his fame, but also to his famously expressive face, which made him an ideal model to convey comedy, tragedy or any other genre. On the other hand, the mobility of his expression sometimes meant that he was a difficult sitter to paint. Thomas Gainsborough reportedly flung down his brush in exasperation because the actor kept altering his expression. A satirical ‘mechanical print’ of 1845 in the British Museum’s collection depicts Garrick sitting to Hogarth in his studio. Behind the print is a disk with thirty different likenesses of Garrick that can be rotated to reveal different expressions.

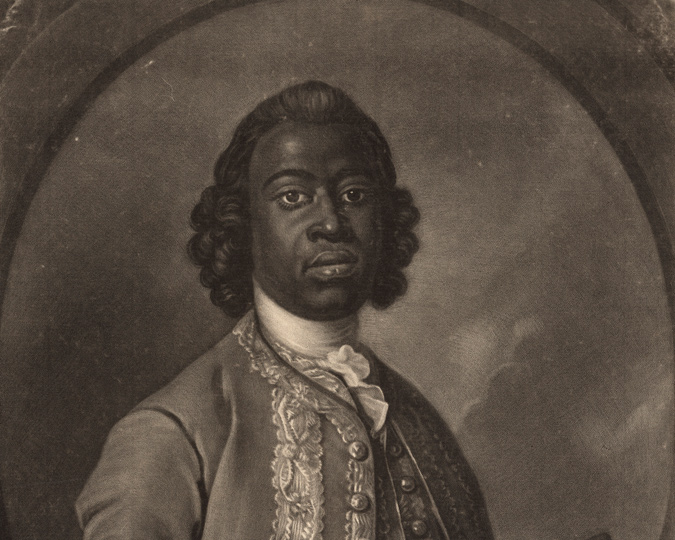

Portrait of David Garrick, 1766-75

In the style of Joseph Wright of Derby. ID no. 56.169/2

Portraitists were also interested in Garrick, the man. There are no theatrics in this late portrait in the museum’s collection. Instead he is shown in ordinary dress, looking directly out to the viewer. On the desk beside him are writing implements, and he points at a sealed letter or document bearing his name. This indicates his status, not only as an actor and theatre manager, but as a ‘man of letters’; a member of literary society. Garrick was frequently depicted in the act of reading or writing, or simply with books and papers, perhaps indicating his desire to be recognised as more than just a theatrical ‘player’.

For many years he hoped to be elected to Dr. Johnson’s ‘Literary Club’ (often referred to simply as ‘The Club’) but was opposed. He was eventually accepted in 1773, which is around the date that this portrait is thought to have been painted (judging by his outfit). He had recently achieved a career highlight by organising the ‘Shakespeare Jubilee’ celebration in Stratford-Upon-Avon in 1769. His expression certainly suggests that he is feeling rather pleased with himself about something.

Brown velvet suit, coat, waistcoat and breeches, 1758-61

David Garrick wore this suit to have his portrait painted. ID no. 28.92

In three of the best-known portraits – all by leading artists – Garrick is depicted in the same brown suit. This was donated to the Museum of London in 1928. The museum also owns a dressing table, said to have belonged to the actor and to be the one he used at Drury Lane.

The most peculiar item of ‘Garrickomania’ in the collection, however, was made long after the actor’s death. This is a model of David and Mrs Garrick (Eva Marie Veigel), made in the 1950s by the renowned diorama-maker Judith Ackland, and donated to the Museum by her artistic collaborator Mary Stella Edwards. Ackland developed her own method for making figures which she called ‘Jackanda’, using wire and compressed cotton wool. The scene is based on another famous painting by Hogarth (Royal Collection), and as such demonstrates the longevity of Garrick’s image, and his continuing fascination to successive generations.

Garrick is remembered as one of the most culturally significant Londoners of the eighteenth century, and, as such, his name has been commemorated with a member's club, a street, and a theatre. There is also a restaurant and a pub named after him. This year he is being celebrated in a major exhibition at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, and various smaller displays and events in London and elsewhere. Three hundred years on, this remarkable man has left his mark on London's cultural life.

References:

- John Brewer, Pleasures of the Imagination, English Culture in the Eighteenth Century, Routledge, New York and London, 1997

- Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Every Look Speaks: Portraits of David Garrick, exhibition catalogue, Holbourne Museum of Art, Bath, 2003

- James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. Including a Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. (1791) A New Edition with Numerous Additions and Notes by John Wilson Croker, five volumes, John Murray, London, 1831