28 March is the birth anniversary of Joseph Bazalgette, the Victorian engineer who masterminded London's modern sewer system. Learn how Bazalgette helped clear the city's streets of poo, and how you're still benefiting from his genius every time you flush.

Why was the sewer needed?

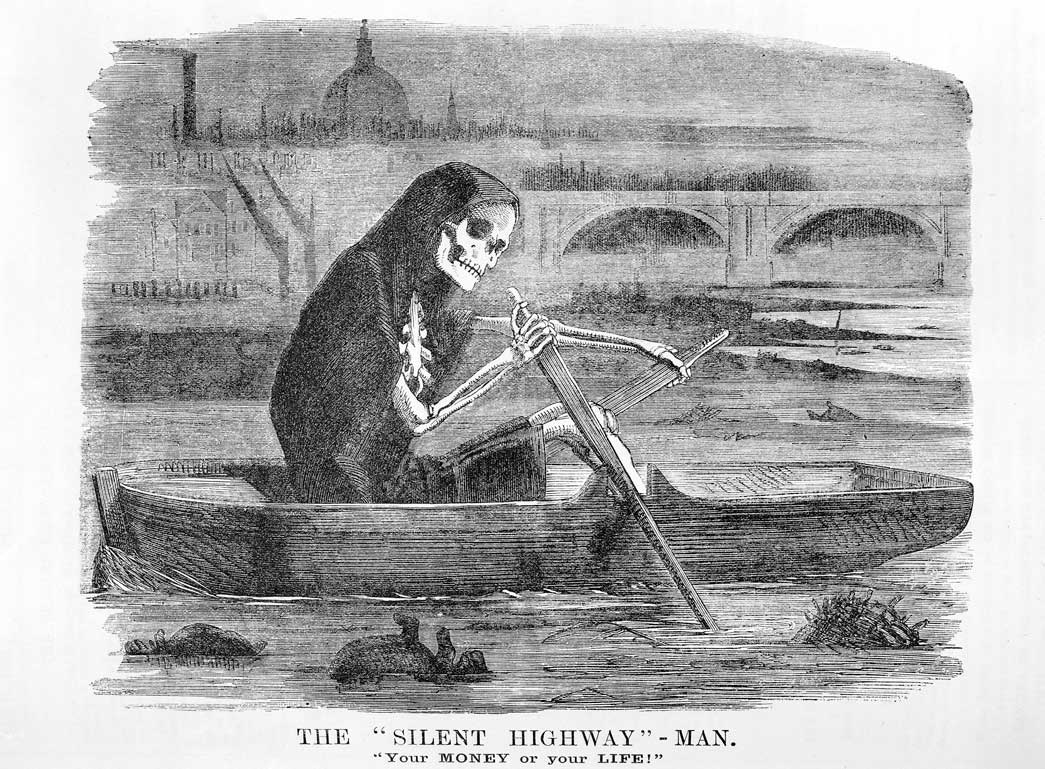

By the middle of the 19th century, the streets of London ran with human filth. For centuries, the city had depended on a patchwork system of local waste disposal, relying on night-soil collectors who would empty local cesspits, and on the city's old rivers, like the Fleet and the Tyburn, now little more than open sewers. The increasing use of the flush toilet only made things worse, letting wealthy families dump their poo straight into the river. Most of the inhabitant's faeces and urine was eventually dumped into the Thames, which also served as a source of water for drinking and washing. The Metropolitan Board of Works had wanted to improve London's sewers for years, but didn't have enough money.

The summer of 1858 saw the "Great Stink" overwhelm London. The hot weather exposed the rotting human effluent and industrial waste polluting the water of the Thames. Water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid fever swept through the population. It was believed that the smell itself, or "miasma", spread these plagues, and those who could afford to fled the stinking city.

Such was the overpowering smell from the Thames, the curtains of the Houses of Parliament were soaked in chloride of lime in a vain effort to block out the smell. It is no surprise that a bill was rushed through Parliament and became law in just 18 days, to provide more money to construct a massive new sewer scheme for London. The Times newspaper said that Members of Parliament had been "forced by sheer stench" to solve the sewer issue.

What was the solution?

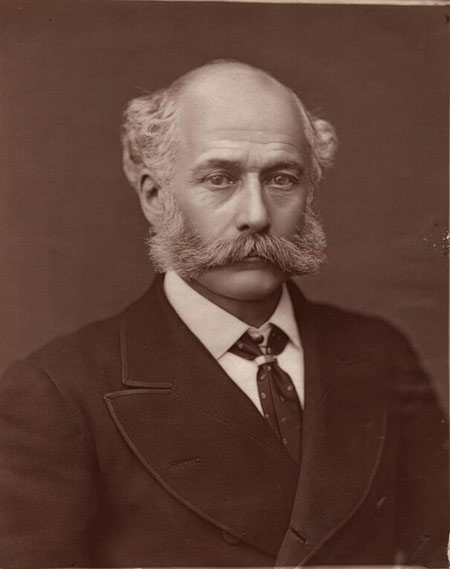

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette, 1877

Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Joseph William Bazalgette was the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, and had been hired specifically to take charge of the new sewers. The cost would be enormous. Parliament initially offered £2.5 million, somewhere between £240 million and over a billion pounds in today's values.

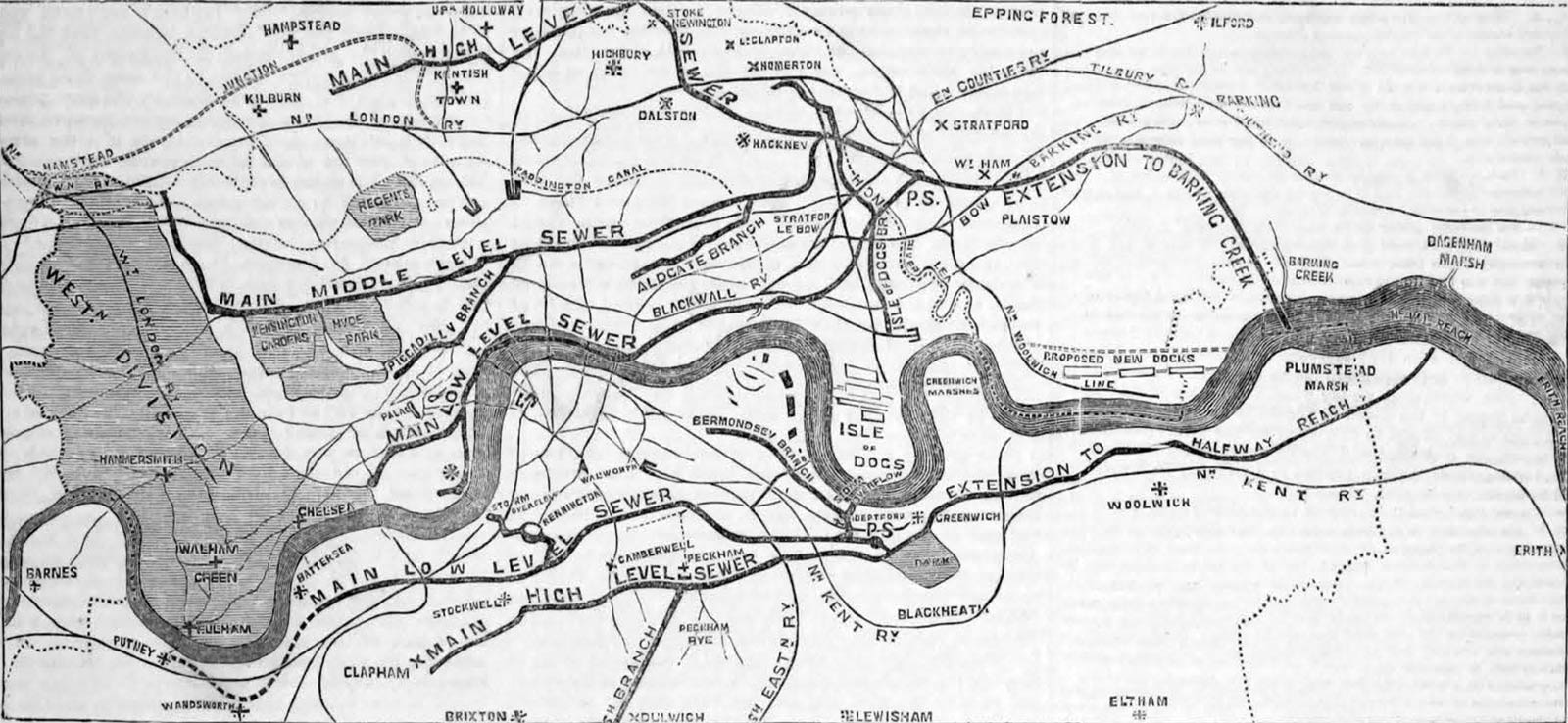

Bazalgette carefully reviewed 137 different proposals to handle the poo problem. Bazalgette's plan was for an extensive underground system of sewers, joining up the patchwork of existing municipal drains. The new system would funnel the waste far downstream of the main city of London, eventually dumping it into the Thames Estuary at high tide.

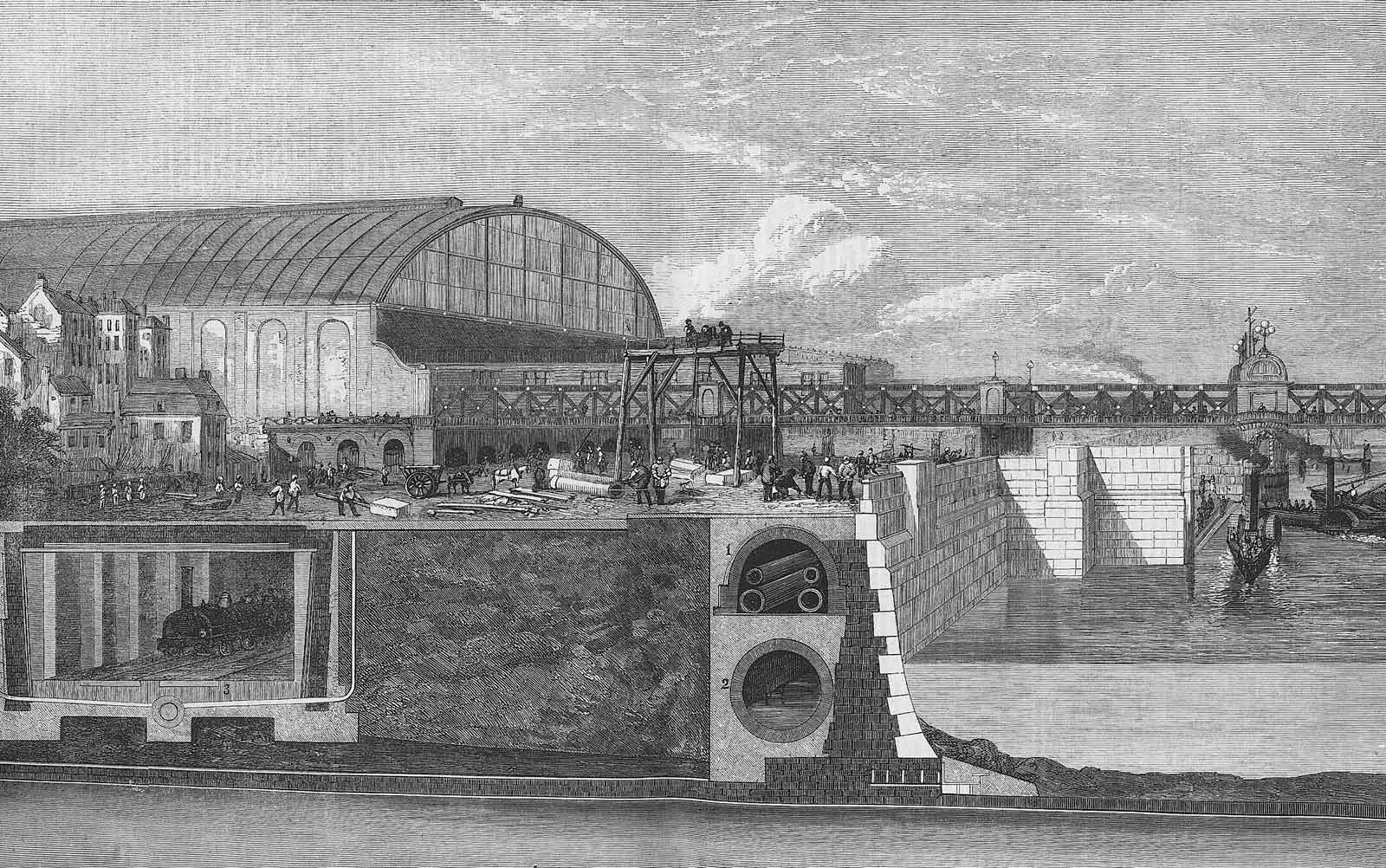

The plan involved building 1,100 miles of drains under London's streets, to feed into 82 miles of new brick-lined sewers, and carry the effluent to six "intercepting sewers". Many of these had once been open streams, and "lost rivers" like the Fleet were brick-lined and covered over to become huge, hidden flows of waste.

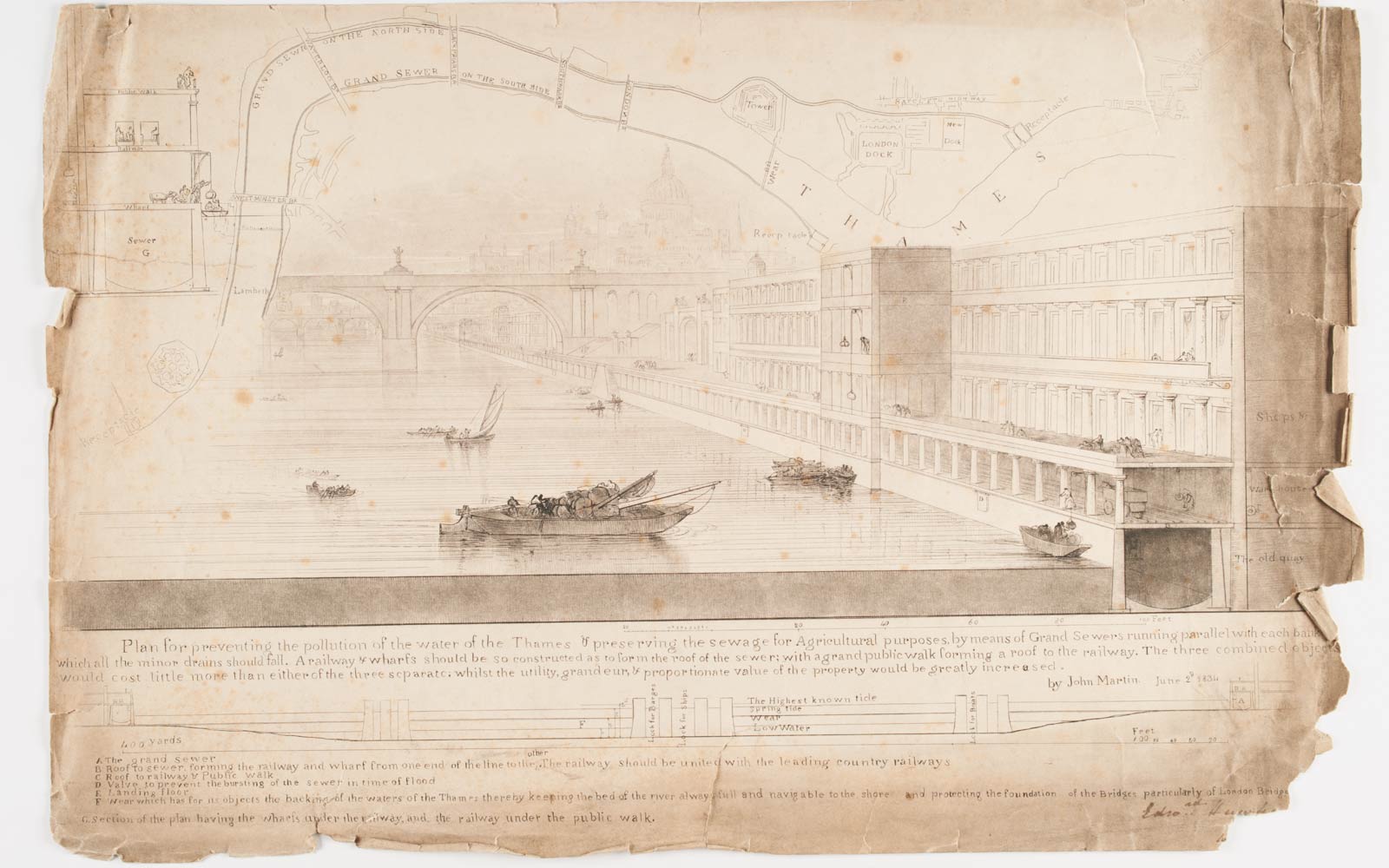

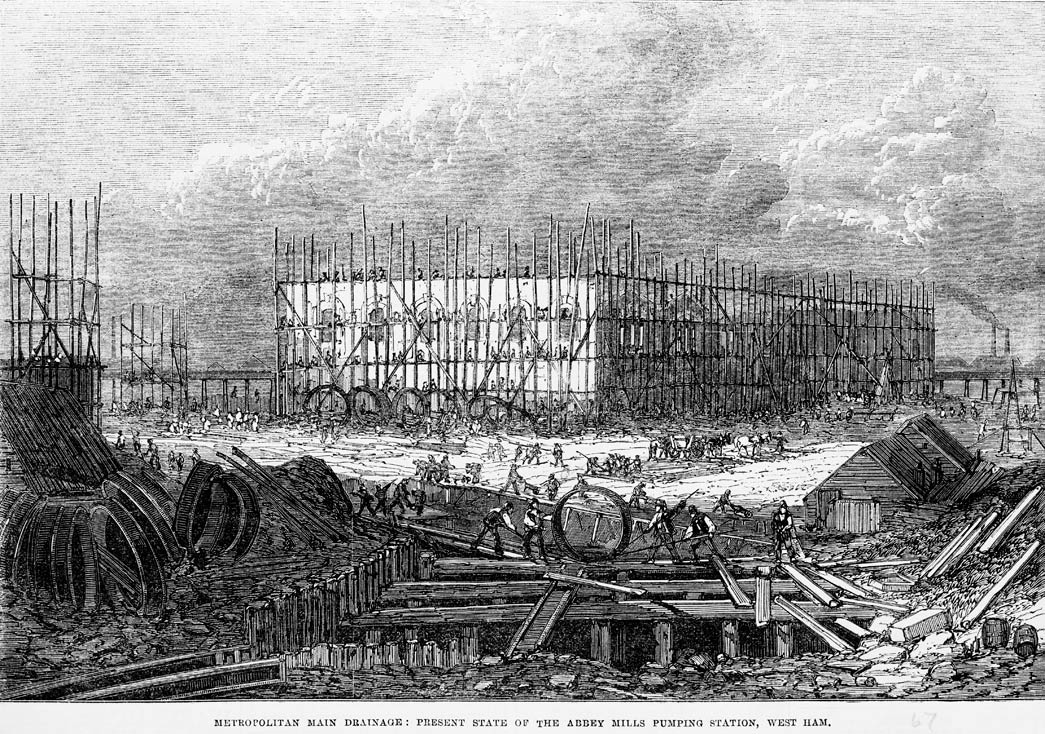

These weren't wholly original ideas: the painter John Martin had proposed something similar 20 years earlier, in 1834 - although he hoped to "preserve the sewage for Agricultural purposes" by funnelling it into gigantic storage tanks which could then be used for manure. Bazalgette's scheme simply dumped the sewage eight miles downstream, via pumping stations at Deptford and Abbey Mills.

At the time they were built, these pumping stations used the biggest steam engines in the world to pipe the effluent up to the mouth of the Thames. The whole project was colossal in scope: it required 318 million bricks and 670,000 cubic metres of concrete. Thousands of labourers were needed to dig out the tunnels by hand, and the demand for workers drove up bricklayers' wages by 20%.

Bazalgette insisted on the use of the the relatively new Portland cement, an extremely strong substance that is also water-resistant. This is one of the factors that has helped the Victorian sewer system survive to this day.

How did the sewers change London?

The plans called for two of the intercepting sewers to run along the north and south banks of the Thames, to catch all the waste flowing downhill. This gave an opportunity to build large new "embankments" along the river, encasing the sewer pipes and also an underground tube line. These new stone constructions narrowed the river, reclaiming about 22 acres of land from the Thames. The Victoria, Chelsea and Albert embankments were all designed by Bazalgette.

Although the system was officially opened by Edward, Prince of Wales in 1865 (and several of the largest sewer channels named after members of the Royal Family), the whole project was not completed until 1875. By then, it could carry 2 billion litres of waste every day, enough to keep running even as the population of London exploded. By the time Bazalgette died in 1891, there were 5.5 million people living and defecating in inner London, over double the number when he first designed the sewers in the 1850s.

How important was Bazalgette?

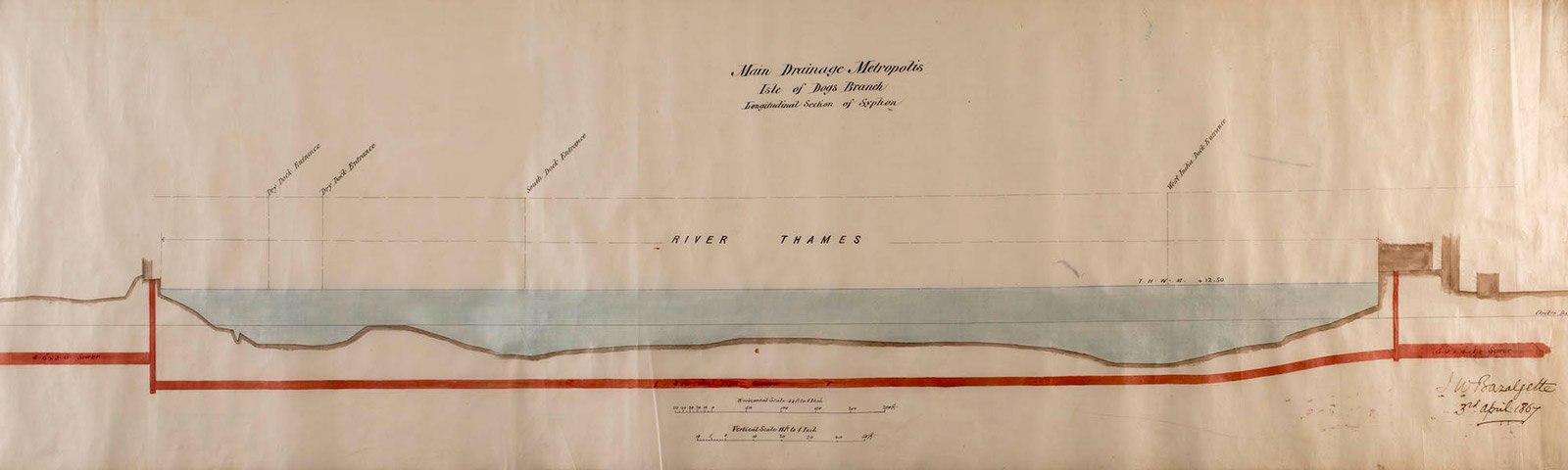

Bazalgette certainly didn't build (or even design) London's sewer system single-handedly, but he was a tireless manager, obsessed with every detail of his work. He inspected every plan that passed through the Metropolitan Board of Works — you can see his signature in the bottom right of this design for sewerage at the Isle of Dogs. Bazalgette also personally visited every interchange between the old drains and his new sewers to check that no waste was escaping.

He also found time to design a number of other major pieces of engineering, including Battersea Bridge, Albert Bridge, Putney Bridge, and early plans for the Blackwall Tunnel. Few people have done more to change the River Thames, or London, than Joseph Bazalgette. But his designs certainly weren't perfect.

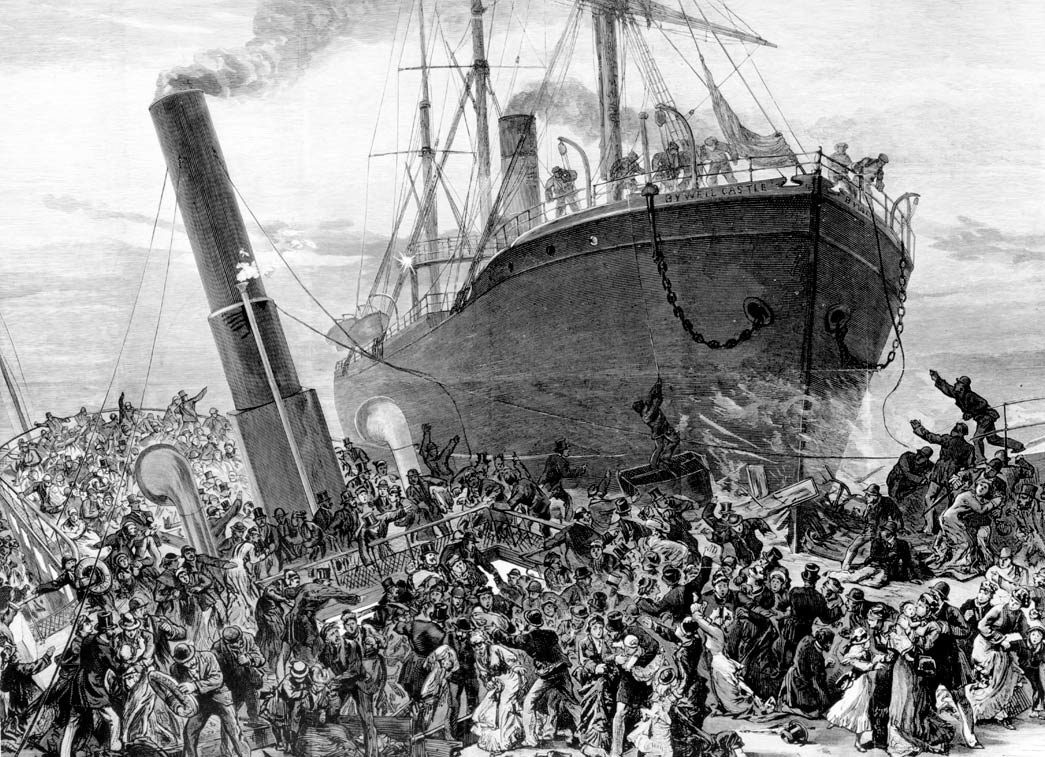

In 1878, soon after Bazalgette's sewers were finally finished, the worst disaster in the history of the River Thames took place. The Princess Alice, a steamboat that took day-trippers up and down the Thames, crashed into a coal-carrying ship, the Bywell Castle. The Princess Alice sank in four minutes, and over 600 passengers were pitched into the Thames — just downstream of Bazalgette's two pumping stations. Just an hour before the disaster, they had pumped 75 million gallons of raw sewage into the river, making the water black and poisonous. Of the 130 survivors pulled out of the Thames, several died from having ingested the liquid waste. The tragedy encouraged the development of sewage treatment plants, to help reduce the amount of pure effluent dumped into the Thames.

Sewage cleaners beneath Lower Thames Street, 1974

Sewer cleaners, Sam Luck (left) & Robert Attwood in a 19th century brick sewer, 1974. Photograph John Eastcott.

The Victorian brick-lined tunnels are still the basis of London's sewer system even today, thanks to Joseph Bazalgette's foresight. Alternative proposals for the Metropolitan sewers proposed narrow-bore pipes, which would have been big enough to carry away the waste of the population of London in the 1850s. By contrast, Bazalgette insisted not only on large tunnels, but doubled their proposed size to accommodate the growth of the city.

Of course, in the dirty 21st century, we're putting new strains on Bazalgette's greatest work.

Some of the sewers have been blocked by fatbergs. These are sticky conglomerates of discarded cooking oil, wet wipes, condoms and poo. In 2017, the Whitechapel Fatberg was the largest ever discovered, anywhere in the world. Its last remaining fragments are now in the Museum of London collection.

More people live in London than ever before, and during periods of heavy rainfall, the combined waste and water still gets dumped straight into the Thames. Major emissions from "combined sewer overflows" happen about 50 times a year. That's why a brand-new super-sewer, the Thames Tideway, is being dug under London. Seven metres wide, this giant tunnel will run for 25 kilometres and intercept sewage that would otherwise pollute the river. Bazalgette would be proud.