Starving yourself for advent? Making a choirboy into a bishop? Iceskating on the Thames? Curator Meriel Jeater reveals the ways that medieval Londoners celebrated Christmas, some ancestors of current traditions, others very definitely not.

Come and celebrate Christmas with us! Visit our Victorian Santa's Grotto at the Museum of London Docklands.

Advent: a time for fasting

The three weeks leading up to our modern Christmas are, for many of us, a time of parties, over-indulgence and Advent calendars filled with chocolate treats. However, for our medieval forebears Advent was a time of fasting. During the fast you were meant to give up meat and animal products like milk, cheese and butter. If you were well-off, you could swap meat for fish instead. Many people at this time couldn’t afford much meat on a regular basis so giving it up for the fast was not as difficult for them as it might be for us today.

Ice skating on the Thames

Detail from 'A Frost Fair on the Thames at Temple Stairs', 1684

General view of the frost fair showing line of booths, coaches, sledges, sedan-chairs and groups of people on the ice.

Ice-skating is all the rage in London these days, with temporary rinks popping up at museums, squares and tourist attractions across the city. In the medieval period the marshes to the north of the city at Moorfields froze over, creating a great spot for skating. The 12th-century writer, William Fitzstephen, describes how people would tie bone skates onto their feet and shoot along the ice ‘swift as a bird in flight’.

In some years, you could go ice-skating in the very centre of the city: on the River Thames. The Thames froze at least 24 times between 1400 and 1835, and in some years frost fairs were held on the river itself. Market stalls, food vendors and entertainments all crowded onto the ice, and the whole of London society came to view the spectacle.

There were several factors that caused the Thames to freeze over in the past but the main reason was the structure of medieval London Bridge, which was finished in 1209. Its 20 narrow arches restricted the flow of the water, slowing it down. When chunks of ice formed in very cold weather, they caught in the arches, slowing the water down even further, leading to the surface freezing solid. A new London Bridge opened in 1831 and the old bridge was demolished. The new design had only five, much wider, arches so the Thames never froze to the same extent again and frost fairs were no more.

Money boxes and boy bishops

Green glazed ceramic money box, 14th century

Normally found broken around the slot where people have tried to get the money out. Perhaps this money box was never used.

The tomb of the Boy Bishop in Salisbury Cathedral

From Charles Knight's 'Old England: a Pictorial Museum', 1845

Money is a common Christmas gift today, and in medieval times Boxing Day on 26 December was when children and apprentices could smash open their money boxes and spend their savings on Christmas treats. If you're interested in knowing what they might have bought with their hard-earned pennies, have a look at our article on medieval festive sweets.

Part of the medieval festivities concerning children that might be less well-known is the tradition of the Boy Bishops. On St Nicholas’s Day (6 December) a boy would be chosen from the choirboys of a church and declared ‘bishop’ until 28 December. His duties varied from church to church (churches in many places across the country had Boy Bishops, including several in London).

He generally wore child-sized bishop’s vestments, sang, officiated at church services, took part in parades and collected money from spectators. The Boy Bishop at St Paul’s Cathedral even had to deliver a sermon on 28 December! The practice of selecting a Boy Bishop was finally outlawed by Elizabeth I.

The Twelve Days of Christmas

We joke that Christmas comes earlier each year, and some organisations are starting to hold their office Christmas parties in November. However, in medieval times the main celebrations didn’t begin until Christmas Day. The Twelve Days of Christmas, from 25 December until 6 January, were a time for fun and feasting.

As well as Christmas Day there were other feast days such as St Stephen’s Day on 26 December, the feast of St John the Evangelist on 27 December, the Feast of the Holy Innocents on 28 December and Epiphany on 6 January. There was a break in the festivities for a while until Candlemas on 2 February where people would take candles to churches to be blessed and feasts were held to celebrate the formal end of winter.

Festive fun and games

Boar hunt, from a Book of Hours, c. 1440

Collection of the British Library.

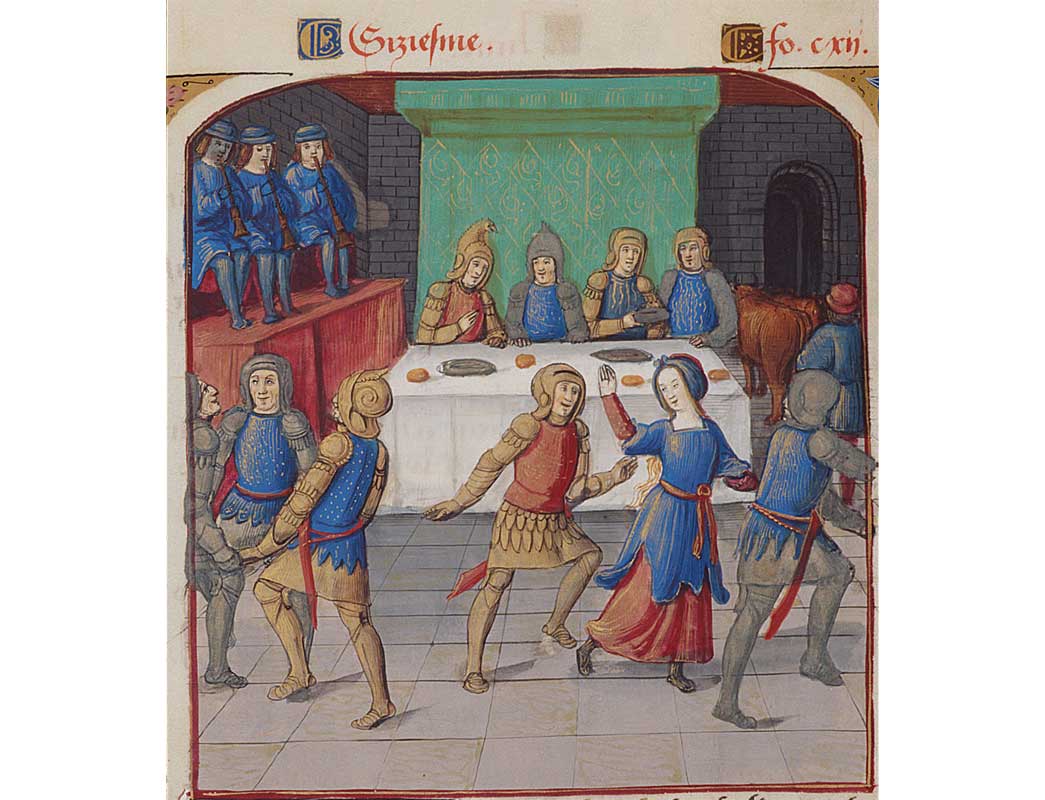

Many of us will spend large parts of Christmas slumped in front of the telly, waiting for the turkey to cook. In 12th-century London, pre-dinner entertainment was rather different. William Fitzstephen writes ‘In winter on almost every feast day before dinner either foaming boars and hogs, armed with tusks lightning swift, themselves soon to be bacon, fight for their lives, or fat bulls with butting horns, or huge bears, do combat to the death against hounds let loose upon them.’

Many of the other medieval Christmas entertainments would be very familiar to us, such as singing, playing games, and watching plays. The medieval equivalents of carol singers were ‘wassailers’ (‘was hail’ meant ‘be well’ in Old English) who went from house to house, singing and handing out wine or ale in return for food or money.

So however you celebrate the festive season this Christmas, the Museum of London wishes you “Wassail”!

Come and celebrate Christmas with us! Visit our Victorian Santa's Grotto at the Museum of London Docklands.