Hundreds of different tongues have been spoken through the long history of London. Let's look back at the changing tale of London's languages, reflected in our collections.

London is one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world and has always been so. From its Roman origins around AD50, the city has attracted people from all over the world. Some early settlers came as invaders, seeking land and wealth. Some came against their will, as enslaved people or servants. Others chose to come as economic migrants or refugees fleeing hardship, poverty and political or religious persecution. They believed London would offer them life changing opportunities.

Today, research has shown there are over 300 languages spoken in London’s schools. Immigrants continue to have a strong influence on the city’s development, from its economic growth to its cultural life. This article looks at a small sample of the communities who came to settle in London from 1675.

French: Huguenot pocket watch

Huguenots (French Protestants) fled to London in the 1680s because of religious persecution in France. Many settled in Spitalfields in east London and set up businesses as silk weavers, creating an industry that survived until the early 1900s.

Other Huguenots were skilled in fine metalwork and engraving. Some Huguenots also brought with them important knowledge and skills from France’s main clock and watch making centres. This pendulum watch was made by French watchmaker David Lestourgeon. He came to London from Rouen in around 1681. Lestourgeon was a Huguenot and worshipped at one of the French churches in Spitalfields.

Like many newcomers to the city, Huguenots gradually assimilated into the London population and stopped speaking French. Of 23 Huguenot churches in existence in 1700, only the French Church in Soho Square survives today.

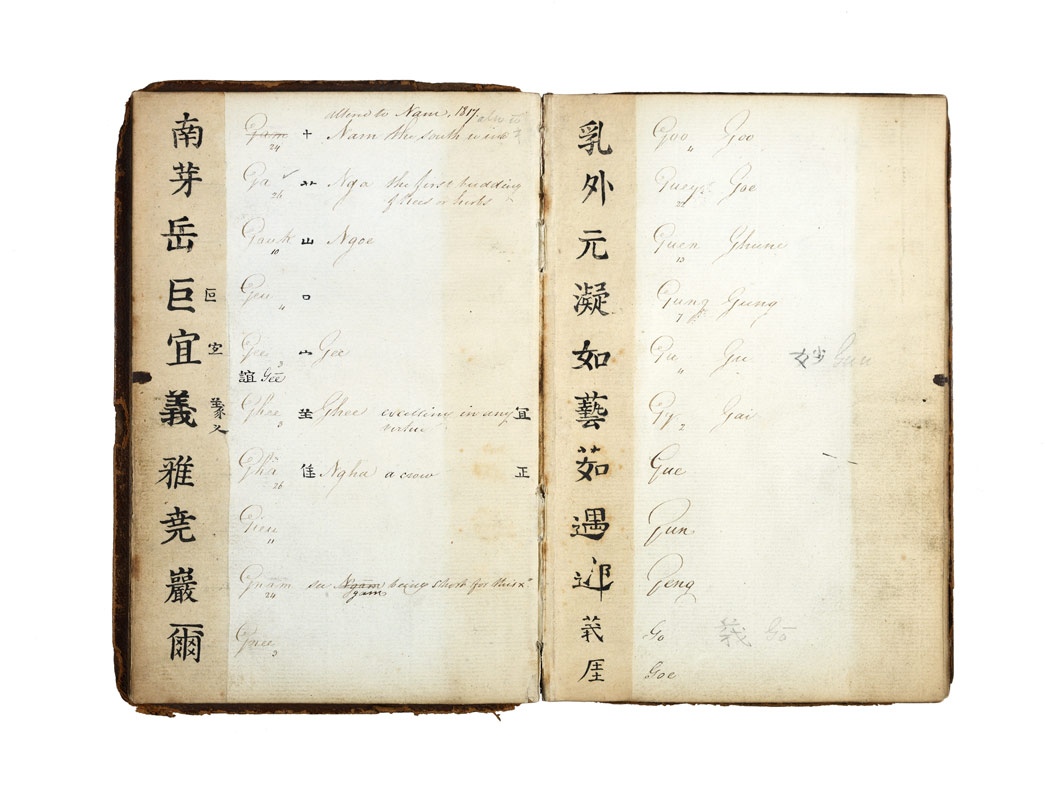

Chinese: "chop book" from the London docks

Chinese language 'chop book', c. 1858

Containing a list of Chinese words with the phonetic pronunciations in the Cantonese dialect and some English translations.

London was once the busiest port in the world, and the docks brought people from across the world into the city. This 'chop book', on display at the Museum of London, would have been used by London dock officials who received tea cargoes imported from Canton (now Guangzhou in modern day China). The book contains a list of Chinese words with the phonetic pronunciations in the Cantonese dialect of Chinese listed alphabetically alongside. This would allow officials to identify the stamps on the side of tea chests and to communicate with Chinese sailors. The notes made by the user of this book suggest that they probably had a basic grasp of the Chinese language. Sailors were some of the first people from China to settle in London, and Limehouse, near the docks, became the first Chinatown in Europe. Over the last two centuries the city has become home to a vibrant Chinese community.

Italian: Clerkenwell's "Little Italy"

The whole area around Clerkenwell was known as Little Italy due to the number of Italian residents and business located there from the 19th century. Some arrived as political migrants in the first half of the 19th century. Others were economic migrants who came to London for a better life with greater opportunities.

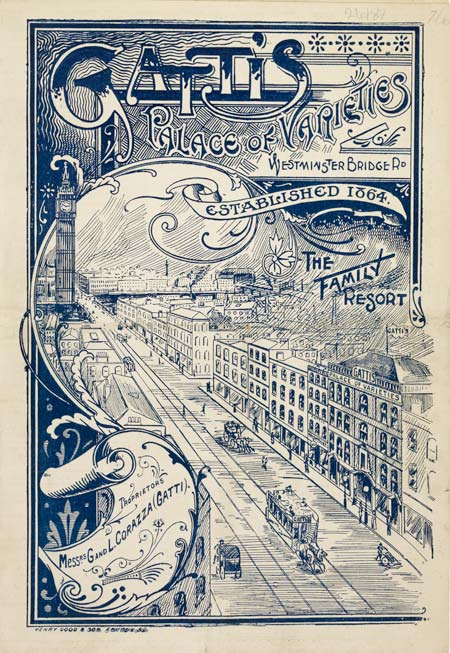

By the 1870s, London’s ice cream and flavoured ice trade was completely run by the Italian community. Carlo Gatti was Swiss-Italian and arrived in London in 1847 as an economic migrant. Originally a street seller, Gatti and his family later operated a number of successful businesses in the capital including cafés and ice cream and confectionery shops. They are credited with having introduced ice cream to London in 1850. Gatti had an ice depot in Saffron Hill at the heart of the Italian community in Clerkenwell.

This theatre programme is for Gatti’s Palace of Varieties on Westminster Bridge Road. The theatre opened in 1865 and could hold up to 900 people. It shows the opportunities available in London to enterprising migrants like Gatti at this time.

Yiddish: the Jewish community of the East End

Jewish New Year Card, c.1910

The banners surrounding the couple are printed in Russian, Yiddish and English with the message 'Happy New Year'.

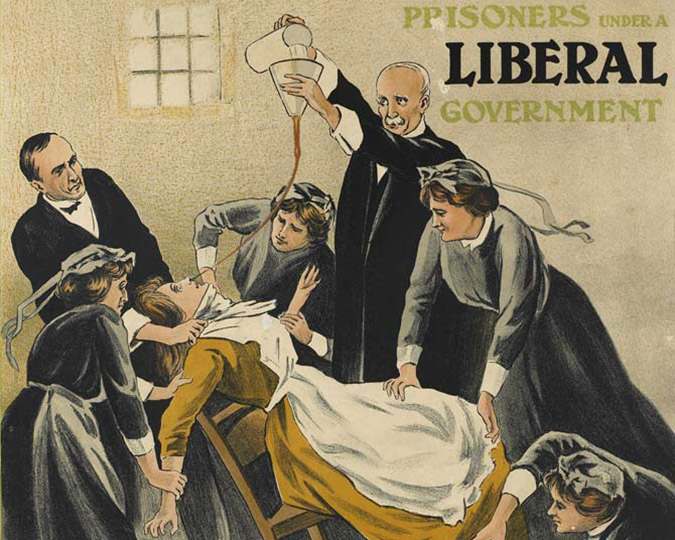

Here's a reminder that speaking different languages hasn't always been celebrated in London. This is a news clipping from an article printed in The Sphere magazine in February 1908.

Entitled 'The Largest of Our Elementary Schools Where Russian Jews are made into Good British Subjects', it describes the work of the Jews' Free School in Bell Lane, Spitalfields, the heart of the Jewish East End. Tens of thousands of Jewish people from central Europe and Russia moved to London towards the end of the 19th century, seeking refuge from religious persecution and anti-Semitic pogroms.

By 1908 the Jews' Free School offered free education to 2,200 Jewish boys and 1,200 girls and was the largest school in Europe. Like many Jewish youth organisations in the East End it favoured Anglicisation and integration. Yiddish culture was discouraged to iron out the 'ghetto bend' in immigrant children, which was thought to prevent them from integrating into British society. Despite this prejudice, London's East End became a thriving centre of Jewish life.

Languages of today

For our November 2018 festival, Languages of London, we wanted to celebrate the many communities of the area around Museum of London Docklands. We worked with local London schools for a poetry competition, asking children to submit poems that express their experience of growing up surrounded by so many languages.

Winner: Linguistic freedom

Tasneen, Plashet school, age 12

At every doorstep, the tongue twists to something new,

In every corner, the voice finds a new melody to play,

It doesn’t hold the ability to become ancient or a tradition,

It is resurrected at every dawn.

It is not always spoken of,

It represents itself in every form possible.

It can be gestured, or heard, or even seen.

Never it is truly solid or pure,

Its colours change and its heart displaced.

It is what governs this life.

You can’t be a beginner at speaking it,

As it is born alongside you.

It takes the ear-mouth road to travel to every corner, to every vein.

You see the situation is complicated,

But the word is its body and it is the tongue.

The inhabitants of this world say that it defines as such: it is the method of human communication, either spoken or written, consisting of the use of words in a structured and conventional way.

But that’s false, because language is whatever you make it!

Runner-up: My Gift

Temiloluwa, Plashet School, age 12

My tongue.

So different to yours,

unique in every way imaginable.

My mouth,

moulds my words in a way that makes total sense to me,

but is completely unintelligible to you.

My dialogue,

at times bland and forceful,

is not worthy to be compared to the calm cohesive tone of yours,

which never ceases to end with its signature exotic ring,

or its roll of the tongue when pronouncing a word containing the letter ‘r’.

Our terms and phrases,

no matter its origin,

reflects the exact emotion wanting to be portrayed by an individual.

Therefore, it doesn’t take a translator to understand what is truly meant.

Our words,

a gorgeous piece of art.

A great splendour.

Such a beauty.

Rich in creativity.

Something to take pride in.

Our voice.

Our speech.

Our tongue.

Our words.

They all make us the people not of the past,

not of our ancestors who haven’t a damn clue of diversity, of liberation, of true freedom.

No, because, you see they lived in a time when each word is to be articulated with such precision,

That we all end up sounding exactly the same.

And being the same as everyone else was not the reason languages were created.

For languages were born,

to glorify and express ourselves as individuals.

To be recognised in a sea of billions.

To be known for who we are,

and who we want to be.

To be loved and desired.

And for those reasons,

languages were made.

So be proud of your tongue!

Be free to speak out!

Because languages make you special.

Languages make you stand out like a bright light that keeps shining amongst the darkness.

And if all that I said is not enough, remember that your language, you voice is a gift.

And this gift of yours is one of the few things in life that no one can ever, EVER be taken away from you.

Runner-up: All in this together

Zaina, Brampton Manor school, age 12

Once I walked down the lane

and I heard somebody say

I am Chinese, Japanese, German, Spanish, French-

but it doesn't matter who you are,

or what language you speak...

We are all in this together,

Every wear and tear and dream.

It doesn't matter what your culture is

or if you're old or young.

Everybody can speak this language

Old or young or smart or not.

If we smile and laugh and love each other

It's clear what we're going to say.

We are all in this together

doesn't matter who you are

doesn't matter what you speak or say

if you laugh or cry or love or play...

Once I walked down the lane

and I heard somebody say

we are all in this together

Every wear and tear and dream.