London’s queer history starts much earlier than you might guess. Curator Francis Grew explores how recent scholarship reveals the presence of same-sex love in Roman London, and how different those relationships were from modern LGBTQ+ lifestyles.

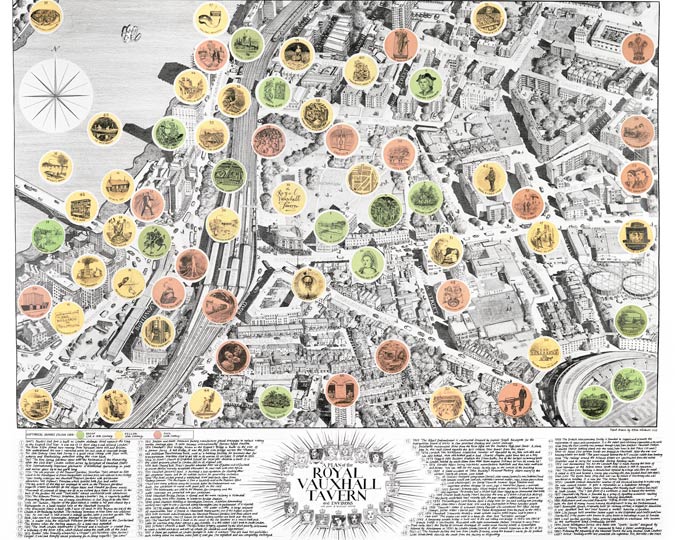

Fibreglass replica of a life-size bronze head of Hadrian found in the Thames in 1834

Original in the British Museum

2022 marked the 1900th anniversary of the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s visit to Londinium. When Hadrian visited the city in the year 122 CE, his entourage included young men with whom he was clearly intimate.

He would have been entirely open about it, and many bystanders will have thought his behaviour quite normal, if only because they themselves had same-sex relationships. But it is only recently that scholars have come to accept that such attitudes prevailed in Roman London.

Forty years ago I was a university student, reading Greek and Latin literature. Since then not only have our attitudes to LGBTQ+ issues changed, but so has our understanding of Roman London. In those days many archaeologists believed that metropolitan Roman culture had little impact upon so distant a province as Britain. This may be true for many regions of Britain, but writing tablets discovered during recent digs in London show that society here was organised in much the same way as in Rome itself, for at least the first century of the city’s existence.

One aspect of this, which is particularly important for understanding attitudes towards LGBTQ+ issues, is that Londinium was clearly a slave-owning economy – something that we preferred to imagine could never have taken root here. No fewer than five of the tablets recovered from the excavation of the Bloomberg Mithraeum site in 2012-13 record business dealings between slaves or ‘freedmen’ (ex-slaves) acting on behalf of their masters.

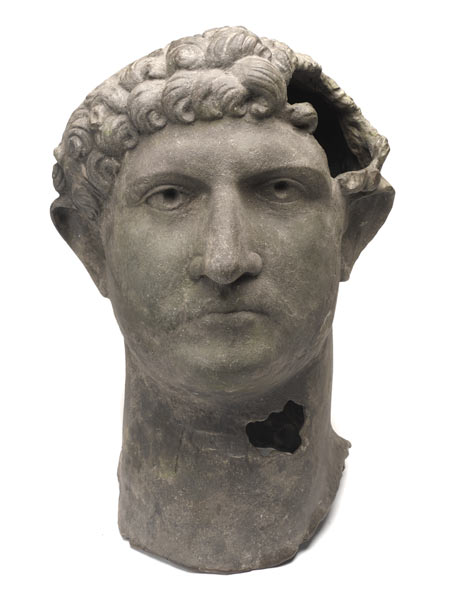

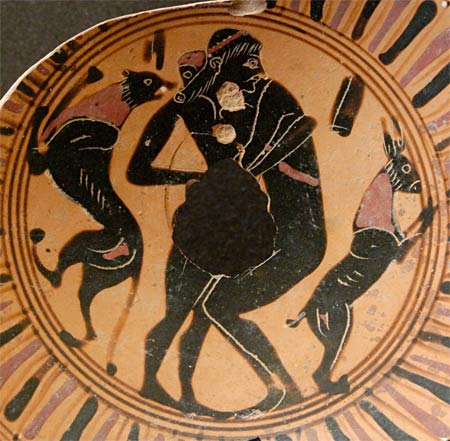

Fragment of an Attic cup showing homosexual intercourse, 550-525BCE

Collection the Louvre Museum. Public domain.

Our understanding of the ancient world has changed radically over the last forty years. 1978 saw the publication of Kenneth Dover’s book, Greek Homosexuality. While it had long been obvious to anyone who studied Greek vase-painting that same-sex relationships were ubiquitous in that society, the matter was usually side-stepped in lectures and student essays. Homosexuality had been decriminalised in Britain just a decade earlier. The photographs for Dover’s book had to be delivered to the printer by hand, because the post might have been intercepted under Section 11 of the Post Office Act (1953), which banned sending “indecent or obscene prints” by mail.

Greek Homosexuality is not a comprehensive account of same-sex relationships in the Greek world. In fact Dover was mainly concerned with a particular type of sexual relationship, between an older man – the active party, the ‘lover’ – and a younger man or boy – the passive party, the ‘beloved’. Such relationships were normal in 5th-century BC Greece, and were seen as a rite of passage for both parties at the respective stages in their lives. The older male would often have female partners. However, given the vastly different social context of ancient Greece, we should resist the temptation to describe such men as ‘bisexual’ in the modern sense. Still, sex between men was deeply embedded in Greek society.

Marble busts of Emperor Hadrian (left, 117-138 CE, probably from Rome) and his lover Antinous (right, 130-138 CE, from Rome).

Collection of the British Museum. Photograph by Dr. Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, Creative commons BY SA.

Dover’s work enabled scholars 40 years ago to explain – even ‘excuse’ – the behaviour of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Eight years after visiting Londinium he founded an entire city in Egypt, in honour of his beloved male sexual partner Antinous, who drowned in the Nile in 130 CE. Hadrian, it was argued, was simply a devotee of Greek culture, who could openly adopt traditional modes of sexual behaviour in places such as Greece or Egypt, but not in the West. We now know that even if this was true, it is at best only a partial explanation.

Hadrian may well have been gay (in the modern sense of being only attracted to other men ). In public he treated his wife Sabina with respect, but we shall never know if they had a sexual relationship. Certainly their long marriage produced no children. And whereas most Roman emperors were repeatedly lambasted for promiscuity with both girls and boys, there is just one, very mild, reference to Hadrian having an adulterous affair with a married woman.

Perfume bottle made of cameo glass found in the Roman necropolis of Ostippo (Spain). 1st century BCE or CE.

Side B of the bottle, portrayed above, shows two young men in bed. Collection of George Ortiz.

There is no need to use Dover’s lover-beloved model to explain Hadrian’s devotion to Antinous, because there is plentiful evidence for same-sex relationships in the second century CE. Sex between a citizen and the wife of another citizen counted as adultery, but there was no law to regulate sex with slaves or others of inferior social status (male or female). It was much more important for a Roman man to preserve his image by being seen to be the superior, active party, and his partner the passive. The idea of ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ did not yet exist - what mattered was to be sexually dominant .

Now we know from documents that the Londinium of Hadrian’s time was a slave-owning society, sharing the same values as citizens throughout the Roman empire, we can be sure that same-sex relationships were normal. But it would be a mistake to regard that society as sexually ‘liberated’ or as having much in common with present-day LGBTQ values and definitions. There is much we should find reprehensible. Both in Greece and Rome many people would have had sexual relationships at a time when, by modern standards, they were appallingly under-age. Disparities of status and power were ruthlessly enforced physically, often with violence.

And what of women? Where is the female voice from the time of Hadrian, to match that of Sappho, the renowned Greek poet from Lesbos? Long overlooked by students of Classical literature, that female voice may well survive, her words engraved on the leg of one of the Colossi of Memnon in Egypt. Julia Balbilla was lady-in-waiting to Hadrian's wife Sabina and an accomplished poet. Remarkably, she accompanied her mistress on the fateful tour of Egypt when Antinous was drowned, and in her verse she deliberately adopted the now-antiquated dialect of Sappho. In one poem, a hymn to the hero Memnon, who was believed to speak through the earthquake-shattered statue, the traditional literary form may well have been cover for more personal feelings. ‘Delighted are you, Memnon’, she writes, ‘by the beloved figure of our queen’. Was Balbilla Sabina’s lover as well as her lady-in-waiting?