The Museum of London has been collecting the memories of Londoners since the 1980s. Our oral history collection now contains more than 5,000 hours of recorded life story interviews from the people who have lived, worked, moved, migrated, found refuge or just passed through London. In the recordings, they talk about their lives and their everyday experiences. As such the collection captures what it was like to be a Londoner during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Listening to oral histories is a way of eavesdropping on history. Official histories, documents and statistics sometimes feel incomplete, as they generally exclude the true range of people’s lived experiences and emotions. Oral histories offer us a more personal perspective of the past and everyday life. They provide first-hand or eye-witness accounts of memories, customs, dialects and past events.

Our oral history collection is one of the most diverse and inclusive collections at the Museum. It gives a voice to ordinary Londoners, whose experiences are sometimes overlooked or whose stories have not been well documented elsewhere. Some of the earliest audio recorded interviews in our collection document the experiences of Jewish refugees, who arrived from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century. Subsequently, the museum has been involved in various projects that sought to capture the experiences of those who have come to London from elsewhere.

In 2002, we were one of the partners of the ‘Moving Here’ project, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. ‘Moving Here’ explored people’s experiences of moving to London over the past 200 years, also including the present day experience of arriving in the city. The oral histories that were recorded as part of that project were acquired by the museum, and include a wide variety of stories and perspectives. Another project that took place in 2004 was the Refugee Communities History Project, for which over 150 oral history interviews were conducted with refugees. It is an extraordinary and unrivalled collection of testimonies of refugees in London, and was featured prominently in our 2006 exhibition ‘Belonging.’ ‘Windrush Conversations’ is a more recent acquisition of oral histories celebrating the Windrush generation and their descendants in London. These recordings were made at the ‘Arrival’ event at the City Hall in June 2018, where Londoners were invited to discuss the themes of migration and arrival.

Oral histories make the past come to life in an engaging and personal way and they help us connect with human experiences that may be similar to, or different from, our own.

Listening to London

As part of our move to a new museum in West Smithfield market, we are exploring new ways of engaging our audiences with our oral history collection – including those recordings that came from the projects described above. Increasingly, audiences are playing a more active role in museums, allowing them to connect with others, to express their knowledge, experiences, opinions and ideas – to have a more personalised relationship with the museum. At the new museum, we would like to challenge the ways we have traditionally made use of our collection, exploring new avenues to uncover peoples' stories about London, and making space for communities to move from static spectators to engaged citizen curators.

This is why we are supporting community researchers to lead their own research projects into our oral history collection, forming new interpretations and highlighting stories that might otherwise have been overlooked. As part of our Listening to London project, these researchers are drawing connections between stories of the past and experiences of today, and deciding how to share their findings. By doing this, we hope to draw on the knowledge of Londoners who aren’t typically involved in museum research. This is a more democratic model of engaging with our collections, which in turn will shape and enhance the kinds of stories that are told in our new museum.

The first collection that we have focused on within the Listening to London project is the ‘Windrush Conversations’. These vivid and lively conversations bring to light the lived experience of different generations of Londoners with African-Caribbean heritage. They celebrate the contribution of these communities to life in London and highlight the hardships they and their family before them faced as part of everyday life in Britain. This collection has not been shared publicly by the museum until now.

Our community researchers Jasmine and Shanice are leading our research into this collection working remotely from their homes during the Covid-19 lockdown, listening and making connections to their own experiences as part of their interpretation. We are excited to be able to share some of the extracts they have chosen to mark 72 years today since the ship Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury Docks.

Jasmine:

"This resonates with me as being a third generation descendant of Windrush myself, it interests me how others identify all sides of their heritage. The clip highlights the internal difficulty of choosing how to merge all parts of a persons' identity. It also relays the idea/experiences of having others chose your identity for you based on their own preconceptions. Which, being mixed race myself, is a notion I am all too familiar with."

Interviewer: Do you feel British?

Interviewee: I don't know if I feel British.

Interviewer: English? You Jamaican?

Interviewee: I’m Jamaican. I’m always gonna be a Jamaican even though I live in England. I’m always gonna, inside of me Jamaica is always, I always talk of it as home. Not necessarily that's where I am going to go and live again but inside of me it’s

Interviewer: Where you came from?

Interviewee: Yeah and inside of me I’m still Jamaican. I can’t say that I think of myself as being British. No I can’t. I live here

Interviewer: I’m from. I’m from

Interviewee: I’ve been here 50 years and I still can’t. I always think of myself as Jamaican.

Interviewer: I’m born here, I’m born here and I sort of feel like a Jamaican. Because both of my parents were born there. I do use the terminology of Black British to kind of, to call myself. Im born in the sixties and to sort of, to kind of call myself, what is my identity? But with my parents both being Jamaican I feel very much, that’s very much part of my identity.

Interviewee: because of, it’s because you kind of grew up in the same way. You sort of grew up in a Jamaican household as well.

Interviewer: yes you grow up in that situation.

Interviewee: It’s not that you grew up in a British household. You grew up in a Jamaican household.

Interviewer: That’s right.

Interviewee: So you’re Jamaican at home. But when you go out and at work and stuff. Maybe you're more British?

Interviewer: That’s right.

Interviewee: It all change when you get home. My kids um, I think

Interviewer: Feel? Half and half maybe?

Interviewee: Half and half yeah. Cuz after yesterday my son said, I mean, oh I’m English. Black people don't normally say their English, people don’t say their English

Interviewer: I know they say their English but have they actually started to say that? Or?

Interviewee: Yeah because people are afraid to , I think people are afraid to say that they are English cuz they are afraid to offend

Interviewer: offend, yeah

Interviewee: English means that you’re

Interviewer: haven’t got any other ties

Interviewee: you’re white. British is a bit different.

Interviewer: British is like, can encompass being Scottish, Welsh, Black, Brown or Asian, Indian,

Interviewee: Kids that are born here who are Black

Interviewer: this that and the other.

Interviewee: When you look at the form it doesn’t say English, does it?

Interviewer: no

Interviewee: It says Black British

Interviewer: It always says Black British. Or do you feel that or, I’m still very torn what to tick sometimes

Interviewee: tick other. Tick other

Interviewer: They go, are you mixed? And I think no my parents are, what does that make me? You know what does it all mean?

Interviewee: Yeah

Interviewer: Somebody called me a Dogler earlier on? Do you know what that means?

Interviewee: A Dogler? Oh yeah they said that, I swear they only say that because you got Asian

Interviewer: yeah because they could see that I had Asian blood, African blood so. Guayana

Interviewee: Guayanese

Interviewer: They call that.

Interviewee: because my friend is Guayanese and she used to debate it.

Interviewer: A Trinidian women called me that she said I thought you were a Dogler.

Interviewee: In Jamaica they would call you a coolie, they used to call me a coolie. It's a bit degrading, it’s derogatory

Interviewer: It is derogatory.

Shanice:

"This is an account of a woman who came to the UK in the 60s when parents her were already there during the Windrush era. The woman recalls her experience of housing (both as a child and adult) and memories of education and school in London. Although she was academically exceptional in school, she recalls how young children, especially young males, were deemed by the state system as ‘educationally sub-normal’. The woman further says that a lot of these assumptions were made because the tests that they gave took no account of cultural differences. I think it’s in an interesting and valuable account of the British education system because since the Windrush era, there are still conversations and questions raised on improving and changing the national curriculum, to not only include the cultural differences, but to also expand on the Black histories and voices from the past being taught in schools all year around aside from Black History Month."

Interviewee: School in London in the 60s for Carribean children was really hard. Unfortunately a lot of our children, especially young males were deemed by the state system to be educationally ‘sub-normal’ and a lot of these assumptions were made because the tests they gave to the children took no account of cultural differences, we even have instances of people being asked, of people not answering the questions correctly just based on the differences in currency we gave them. There weren’t pounds, shillings and pence at that time. I was very fortunate in that although I went to a really good school in the Carribean, when I came here, for some reason - still unknown to me - I was one of the fortunate few (well, the fortunate one) in my school to be placed in the O-level stream, and therefore that’s what I did. But even though my classmates were, there weren’t many Black kids, asked if they were lucky to do the CSEs. Anyway, I’ve been fortunate in that I did what I did, studied hard at school, even actually got prizes. I got a job, I worked in the civil service all my life, and it was fortunate that I eventually got a promotion and was able to buy my own home eventually.

You can listen to more of the stories our community researchers have selected here.

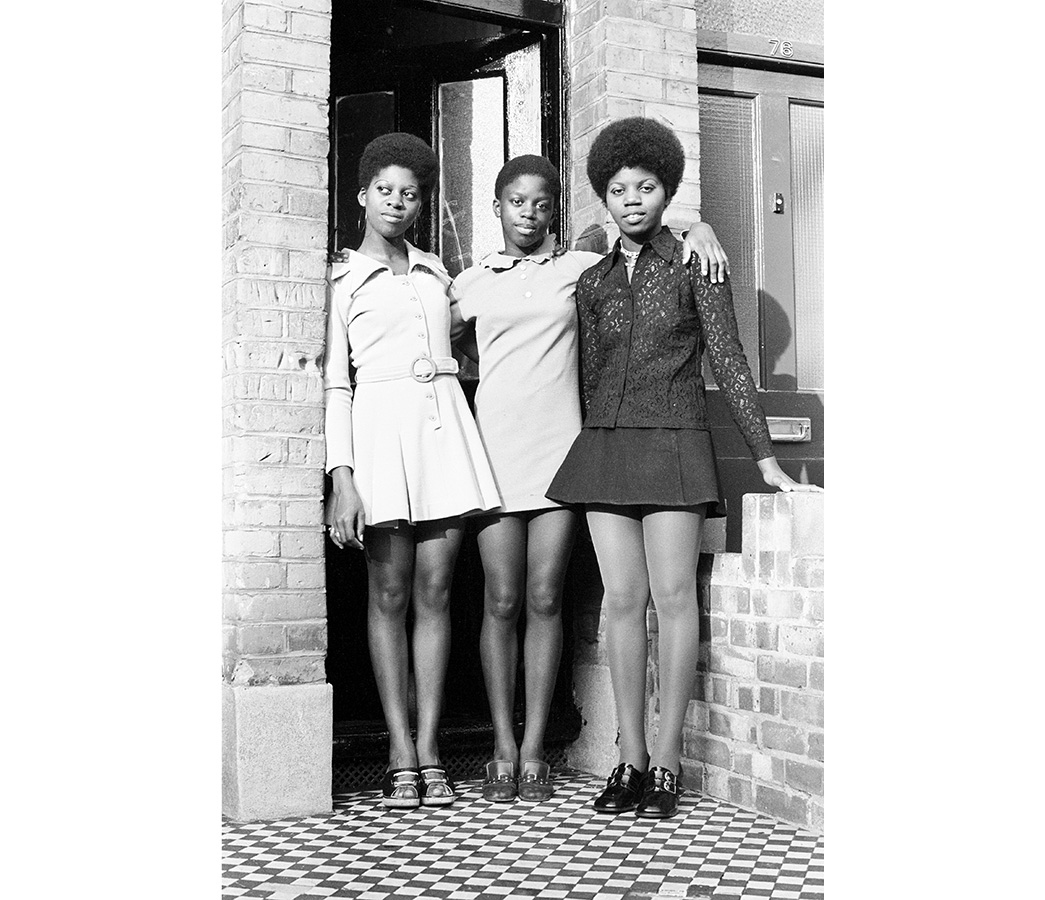

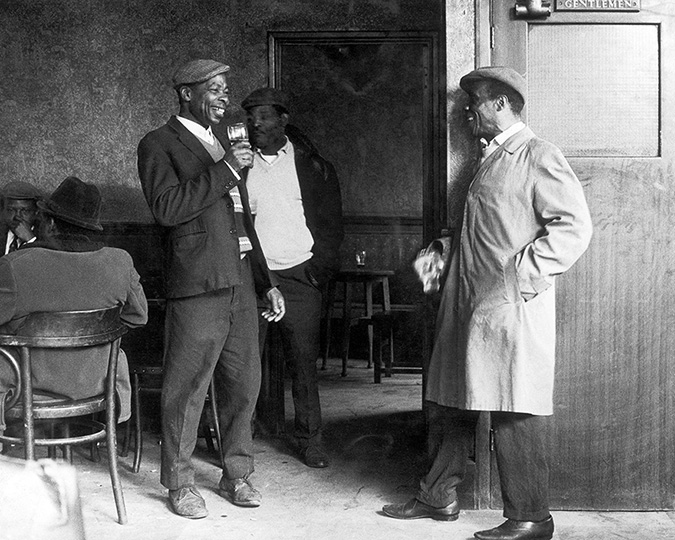

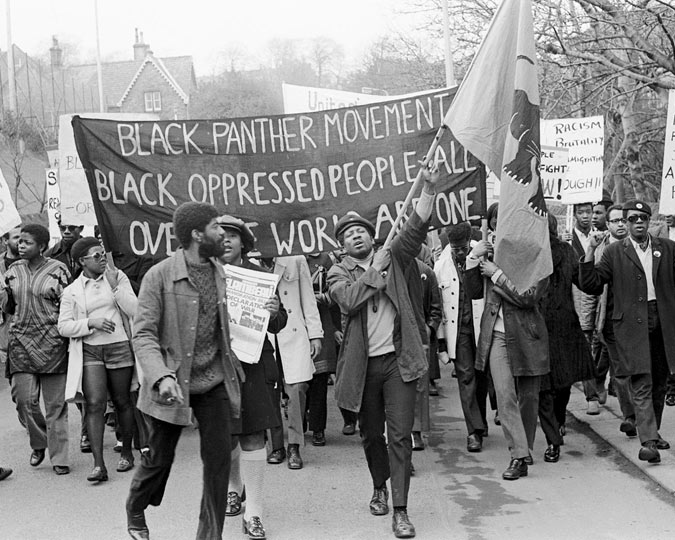

The photographs that illustrate this article were taken by Neil Kenlock and Charlie Phillips, two exceptional photographers belonging to the Windrush generation. Their work forms part of the museum’s Historic Photographs Collection and documents the everyday experiences of African-Caribbean Londoners and the challenges they faced while creating a home and community in British society in the decades following the Second World War. Alongside the work of other photographers such as Armet Francis, Roger Mayne, Henry Grant, Paul Styles and Paul Trevor, their photographs form a rich visual record from which to reflect on London’s histories of migration.

Header image: Arthur Wint, Jamaican High Commissioner, Visiting Brixton, 1975 © Neil Kenlock / Museum of London

Listening to London is supported by The Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund - delivered by the Museums Association

Listening to London is supported by The Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund - delivered by the Museums Association