As part of our City Now City Future season, we've asked writers to imagine how the city might change over the next 100 years. This month, Jonn Elledge, editor of CityMetric, wonders where the Londoners of the future will live.

Protected view of St Paul's Cathedral from King Henry's Mound, Richmond Park

The cathedral is 15.5 km distant from the view point. Creative Commons licence, CC-BY-SA.

For most of the later 20th century, London was half empty. The population of the Greater London area peaked at around 8.6 million on the eve of World War II. Afterwards, thanks to a combination of cheap cars, slum clearances, the government’s New Towns policy, and the Luftwaffe, it began to empty out. By 1981, it was just 6.6 million.

One side effect was that, in the later 20th century, housing in London was relatively plentiful. The city has many restrictions on what you can build where: the green belt, which prevents the city’s outward growth; protected views, such as that which guarantees you can see St Paul’s from Parliament Hill. But for a long time this wasn’t a problem: we could protect good things about the city, without unintended consequences.

Kennistoun House rent protest, Kentish Town, 1960

Henry Grant. Council house tenants Don Cooke and Arthur Rowe led local protests against rent increases by St. Pancras Borough Council.

In the 1990s, though, things began to change. The decline of dirty old industries meant city centres became pleasant places to live once again, and – helped, one suspects, by a string of TV shows set in Manhattan – suddenly urban living became aspirational. The city’s population began to rise, slowly at first – then, since the turn of the century, faster than it had fallen. In early 2015 it’s thought Greater London’s population passed its previous peak. Today, London is bigger than it has ever been.

Bigger, at least, in terms of its population: physically, the city is still restricted by those planning restrictions, and London’s housing stock has not kept up with demand. In all, the authorities estimate that London needs around 50,000 new homes every year. On average, since the early 1980s, it has built fewer than 17,000 a year.

The resulting price rises are great, if you happened to be a long-term owner of a London home (or, better yet, several). For others, though, the result has been unaffordable property prices, increasingly eye-watering rents and over-crowded house shares.

So – how can we fix this? What are our options for housing the Londoners of the future?

The problem of land

Old River Lea looking south from the bridge connecting Manor Garden Allotments to Waterden Road, 2007

Mike Seaborne. Part of a photographic series documenting the site cleared for the 2012 Olympic Park.

The key problem facing the housing market is lack of land: put simply, we have run out of places to build. Debate tends to focus on “brownfield”, a word which brings to mind visions of derelict sites currently going to waste. But London doesn’t have that much of that: a 2016 report from housing charity Shelter noted that, to build 50,000 homes using brownfield alone, we would need to build the equivalent of four Olympic Parks a year, on top of what we were already building.

One option for tackling the space shortage would be to extend London outwards: reviewing the green belt which has restrained the city’s growth since the 1950s. There’s a lot of this – over a fifth of land within Greater London itself is classed as green belt – and the Adam Smith Institute, a free market think tank, has argued that releasing just 3.7 per cent of it could produce a million new homes within walking distance of a railway station.

There is little political appetite for such a move, however: a majority of the electorate still wants the green belt to be sacrosanct, and mayors and general election manifestos alike have repeatedly promised to protect it.

Moves to relieve the housing crisis, then, are likely to involve densification: knocking down chunks of the existing city and rebuilding at higher density.

Going up

The Gherkin or the Swiss Re Building, 2010

A skyscraper in the City of London, this building is 180 metres (591 ft) tall, with 40 floors.

When you picture a high density city, you probably picture Hong Kong or New York City. And one of the big changes in London over the past few years is that it’s become home to a growing number of skyscrapers. As recently as 2000, St Paul’s Cathedral was the 15th tallest building in London. Today, it barely makes the top 50. This year’s London Tall Building Survey found that another 455 skyscrapers are planned, of which 420 are intended for residential use.

But London is still a long way from looking like Manhattan. And there are other models of high density housing. Paris houses around 21,500 people per square kilometre. Even the most densely populated London borough, Islington, only manages 15,670 per square kilometre. Paris achieves its greater density not through skyscrapers, but through mansion blocks, six or seven storeys high. Most Londoners, by contrast, still live in houses – and houses take up more space.

So the solution put forward by the pressure group Create Streets is simple: be more like Paris. Its proposal for the redevelopment of Mount Pleasant, in Clerkenwell, involved mid-rise mansion blocks with narrow frontages. Each would have its own front door, and shops or bars on the ground floor, to give the development the atmosphere of a bustling street, rather than a block of flats. Throw in some decent design and, polling suggests, even those local people most suspicious of redevelopment might approve.

Such proposals currently face two problems. One is that they are often stymied by planning rules, which nudge developers towards boxy architecture with big main entrances. The other is that pesky lack of land again. Sites on the scale of Mount Pleasant rarely come up, and because so much of London is occupied by individually-owned homes with gardens, that’s unlikely to change.

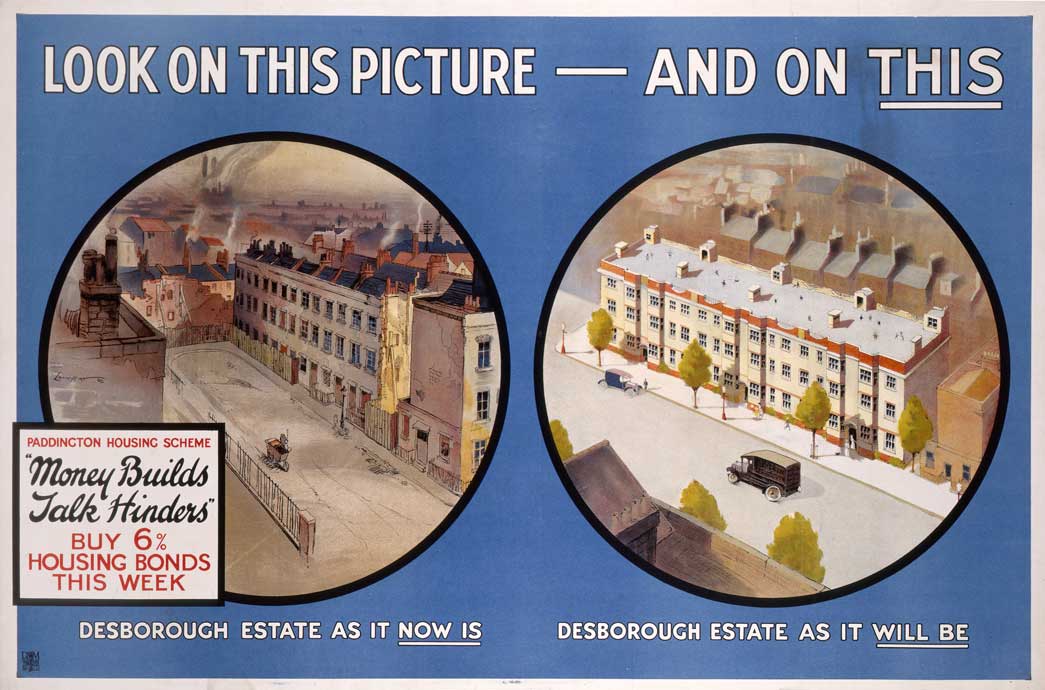

The regeneration game

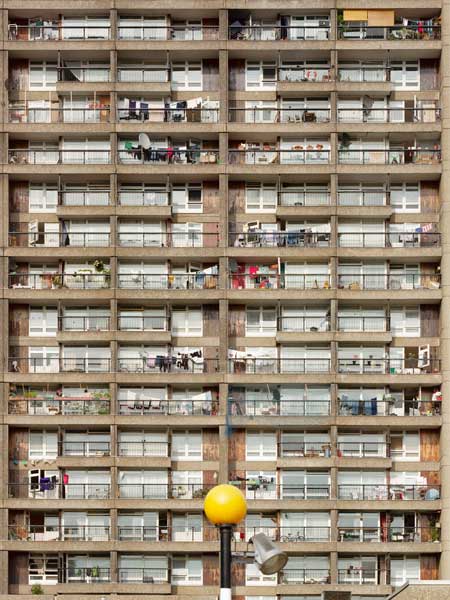

Facade of Trellick Tower, Cheltenham Estate, 1997

Mike Seaborne. 31-storey Trellick Tower was designed in 1966 by architect Erno Goldfinger. After experiencing a spike in crime and anti-social behaviour in the 1980s, Trellick became a highly desirable residence as Notting Hill gentrified in the 1990s.

So if we can’t grow out, and we’re not going to grow up, what can we build?

In recent years, much of London’s housing debate has concentrated on the biggest chunks of land the public sector already owns: council estates. In 2015, Labour's Lord Adonis proposed redeveloping some of London's 3,500 estates as new “city villages”.

These estates are often surprisingly low density, thanks to things like garages and the empty space between blocks – so regeneration schemes can make a big contribution to housing supply. The Woodberry Down estate in Manor House originally included 1,980 homes; once completed, the regenerated site will include over 5,500. The Heygate, in Elephant & Castle, once had 1,200 homes; it’ll soon provide over 2,500.

But – it won’t surprise you to learn this by now – there’s a problem: these estates are already occupied, and demolishing people’s homes is a tricky business. Both the schemes mentioned above have proved controversial, with claims of broken promises to tenants and inadequate provision of social housing. Solving London’s housing crisis at the expense of the poorest Londoners will likely be a bitter pill to swallow.

A less disruptive version of estate regeneration is offered by firms like Pocket Living. The company provides modular housing, pre-fabricated units which can be placed in some of those empty spaces on council estates. The resulting homes are tiny – but they’re relatively cheap to build, and they allow councils to increase population density without evicting existing owners.

The truth is that none of these ideas are likely to be sufficient on their own: fixing this mess will involve elements of all of them. What is clear, though, is we need to do something. London’s population is likely to hit 10 million people within a decade. By 2050, it might hit 13 million. Housing those new Londoners will mean extending the city, whether outwards or upwards. Either option means that unpopular choices lie ahead.

Jonn Elledge is editor of CityMetric and a writer for the New Statesman. His views do not necessarily reflect those of the Museum of London.

Find out how cities around the world, from London to Sao Paolo, are solving the problems of urban living in our free exhibition The City is Ours, on display until 2 January 2018.