As we face the increasing privatisation of London's public spaces, curator Alex Werner looks back at how the city's commons were preserved in earlier centuries.

Our City Now City Future season looks at how to survive on an urban earth.

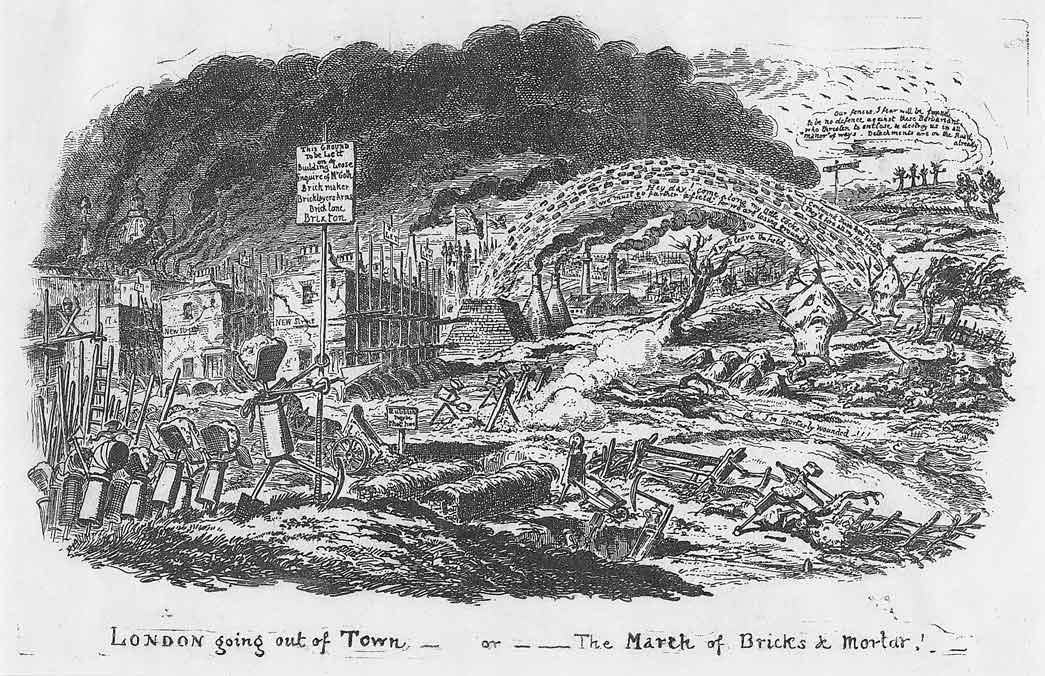

Today, with local authorities stretched to pay for essential services, there is a pressure to sell off buildings and land. We see libraries converted into private gyms and school playing fields sold off to leisure and housing companies. We face the question of which parts of our modern city should remain in public ownership. But London has faced similar pressures before, notably in the nineteenth century. Rising population and wealth fueled a ‘march of bricks and mortar’ over much of the surrounding countryside as London expanded outwards. One-time villages such as Hackney, Islington and Kensington lost their sense of separateness, speculative housing covering over the green fields in-between. In 1822, William Cobbett noted the pace of development on the main route out of London towards Croydon; there were, ‘erected within these four years, two entire miles of stock-jobbers’ houses on this one road, and the work goes on with accelerated force’.

London Going Out of Town or the March of Bricks and Mortar: 1829

Print by George Cruikshank. Regiments of new streets march ruthlessly out of London into the surrounding country under the leadership of 'Mr. Goth'.

'Mush-Fakers' and Ginger Beer makers: c.1877

Street sellers on Clapham Common in the era of London's explosive growth. ID no. IN645

The demand for new houses was never-ending. In the first half of the nineteenth century, London’s population grew at a dramatic rate, rising from around one million in 1800 to two and half million at the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851. There was no let-up in the second half of the century, as the city expanded further to reach over eight million by 1914. Housing developments mushroomed around London, consuming farmland, market gardens and common land. An army of labourers descended – bricklayers, carpenters, joiners, plasterers, glaziers and painters – to produce the now familiar rows of terraced houses as well as accompanying shop parades, school buildings, churches and libraries.

The Japanese Garden in Peckham Rye Park

The crunch moment in terms of open spaces and urban sprawl was probably the 1860s. Londoners, and the politicians who represented them, began to realise that green spaces were being lost at an alarming rate. Often the land was viewed by local inhabitants as common land. In 1866, an act of parliament enabled parishes to use income from the rates to buy and maintain common lands.

Close to where I live, there are two open spaces - Peckham Rye and Goose Green. Both of these were threatened in the 1860s when the lord of manor proposed to develop the land for housing. The new railway lines were spreading across south London at a rapid rate, driving up land values. Even the commons were considered ripe for development, unless protected by local government. With the new act in place, the Camberwell Vestry, the local authority at the time, was able to acquire both Peckham Rye and Goose Green, securing them as public open spaces.

Wandsworth Common pond; 2009

This was happening all over Greater London. Sometimes the land was bought for the public, and in other areas legal protection was secured through the act of parliament, with ‘common land’ protected even if rights were retained by the land owner. In the 1860s, local people mounted a campaign to save Wandsworth Common when it was threatened with development. A long campaign ensued leading to the Wandsworth Commons Act in 1871 which secured it for public use. In 1912, the LCC purchased a further 20 acres extending the common.

The Corporation of London came to the rescue on a number of occasions when open spaces in parts of outer London when probable development loomed. In 1892, it purchased the remaining part of West Wickham Common, now in the London Borough of Bromley. The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was another active body in the acquisition of open spaces. For instance, Hampstead Heath was threatened in the 1860s and finally became public property when the MBW took it over. It expanded in the late 1880s when Parliament Fields was acquired, largely through the philanthropy of Baroness Burdett-Coutts. Plans to develop the surrounding farmland continued apace in north London. In 1907, the area known as Hampstead Heath Extension was acquired with the help of Henrietta Barnett. She went on to develop Hampstead Garden Suburb after buying a large parcel of land from Eton College. The London County Council (LCC) set up in 1888 took over the responsibilities of the MBW for London’s open spaces.

When we spend some time enjoying one of London’s many fabulous parks and commons, we should remember to say a quiet thank you to our forebears who campaigned to secure and safeguard these open spaces for the benefit of all Londoners.