Beatrice Behlen, senior curator of fashion, tells us of her quest to find the fashion houses of Lucile, a designer from the turn of the 20th century.

In the last few years, I have become more and more interested in what I like to call ‘sartorial geography’. I am particularly fascinated by the premises of vanished fashion houses (and I am not alone).

I became particularly obsessed with hunting down the premises of Maison Lucile around five years ago. Lucile was the nom de couture of Lady Duff Gordon, née Lucy Christiana Sutherland, divorced Mrs James Wallace, arguably the first English dress designer working in London who achieved international fame. I wanted to find the exact location of Lucile’s establishments in and around Hanover Square.

17 Hanover Square

Lucile's fashion house, at 17 Hanover Square, as depicted in her autobiography

I knew she had premises at both nos. 17 and 23 but what were their coordinates? After looking it up online, I eventually made a pilgrimage to the West End, only to discover that the present no. 17 did not look anything like the building in the photo the designer used in her autobiography Discretions & Indiscretions. In fact, when you are standing in Hanover Square it is obvious that there has been rather a lot of change in the last century.

A few words about our couturière: Lucy was born in London in 1863, the first of two daughters to Canadian parents. In 1884, aged 21, Lucy followed her mother’s example and married a much older man for all the wrong reasons. James Stuart Wallace, a wine merchant, seems to have taken rather enthusiastically to his wares. After the death of her stepfather in 1889, Lucy, James and the couple’s young daughter Esmé moved in with Lucy’s mother and sister at 25 Davies Street, which has since been demolished. This situation was probably not ideal and James also developed (or gave into) his penchant for ladies of the stage. In 1893 Lucy petitioned for divorce (granted two years later), which was a brave decision, as at the time it was considered disreputable.

Around this time Lucy set up as a dressmaker calling her establishment ‘Maison Lucile’. Choosing a French sounding name for a fashion business was not unusual and Lucile seemed an obvious choice. I wonder whether she was also influenced by a romantic tale of love lost, found and lost again published in 1860 by ‘Owen Meredith’, the penname of Robert Bulwer-Lytton, first Earl of Lytton. ' Lucile', a novel in verse, remained popular throughout the century and one of the many later editions happens to have seen the light of day in 1893.

At first working from home, in 1895 ‘Mrs Lucy Wallace’ is listed in a commercial directory as court dressmaker based at 24 Old Burlington Street. A few years later, in 1897, Lucy moved to 17 Hanover Square and she seems to have been installed at 23 Hanover Square in 1904. There was a temporary move, probably between 1903 and 1904, to 14 St George’s Street (off Hanover square), further details can be found in Randy Bryan Bigham’s book which I stupidly only read after doing a lot or research myself. What is certain is the wedding of our single-mother-divorcee in May 1901 to the Scottish aristocrat, Cosmo Edmund Duff Gordon, who not only sported a rather fabulous moustache but also excelled at fencing. Sadly they did not live happily ever after, but this is another story. Let’s get back to real estate.

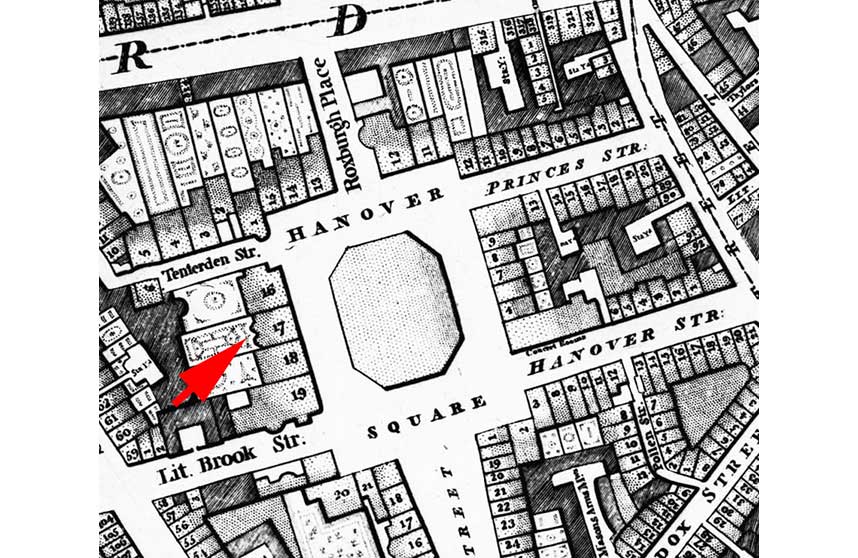

Searching for plans with house numbers lead me to Square 2B of Richard Horwood’s Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster the Borough of Southwark, and Parts adjoining Shewing every House, published in 1792-1795. This confused me for a considerable time as the plan shows no. 17 on the western side of the square when the above mentioned photo suggested it was in a corner, and no. 23 does not seem to exist at all. Hoping to find a helpful photo, print or some such thing in our collection, I typed Hanover Square into the Museum of London's database. One of the records that came up had an extremely sparse description, but also, thankfully, a less clear version of the image below attached to it (otherwise I might just have dismissed it). That image popping up on my screen was pretty much the most exciting thing that happened to me that week.

To the right is a photo taken of one of a set of four glass negatives that depict houses in Hanover Square and seem to have been taken at the same time (more on the other images hopefully in another blog). The Maison Lucile sign alone gives us a rough idea of the date: after 1897 and before 1904. Clues in one of the other photos suggest the later end, but not with any certainty. Sadly, at this point, we do not know how the negatives came into the possession of the Museum, a quirk of some of our early photography holdings.

Having not had much exposure (pun intended) to glass negatives, I was amazed at the amount of detail they contain. The clearly visible street sign immediately solved one problem: no. 17 stood on the corner of Tenderden Street in the north-west corner of the square, Today, a completely different looking building with the same number stands. I might have made my quest easier to go and visit.

One of our negatives also shows very clearly that Maison Lucile shared premises with the stained glass manufacturer Mayer & Co. Mayer was founded in Munich in 1847 and had opened a branch in London in 1865, but not at no. 17. This had been occupied from around 1865 by The Arts Club which, luckily for us, was photographed in August 1896, presumably to take stock before the club moved to 40 Dover Street in the same year, where it is still based. Have a look through these photos on the English Heritage site, to discover what Lucy must have seen when she inspected the house. The second entrance shown in our photo must have been added to ensure that stained glass afficionados and society ladies did not have to rub shoulders. I wonder whether Lucy know or cared that Charles Dickens had been a member of the Arts Club?

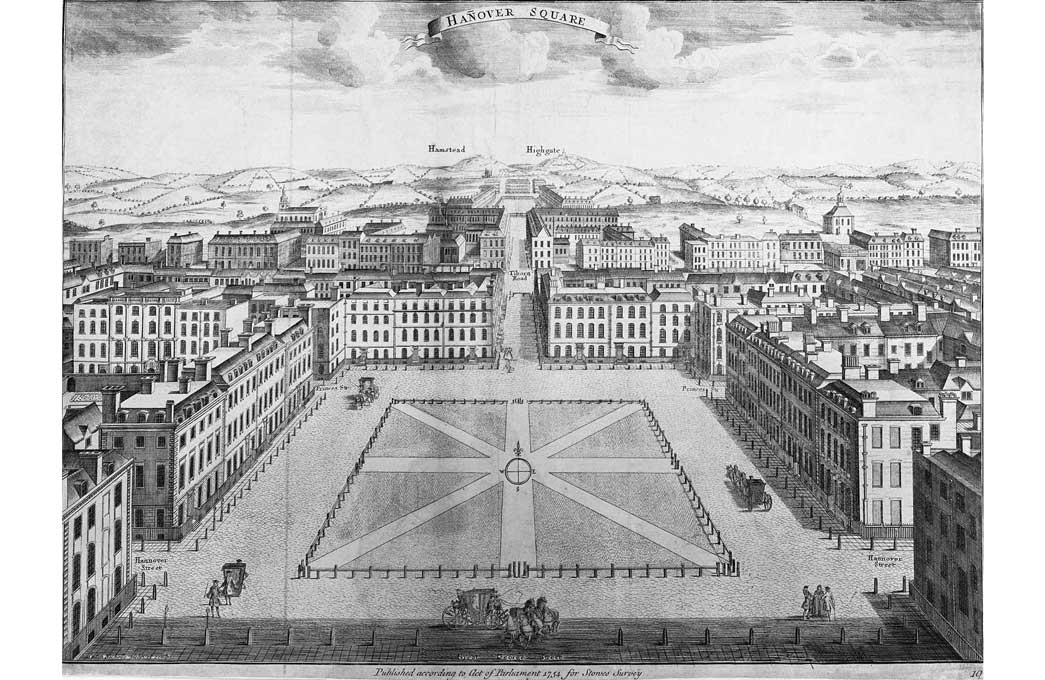

According to 'The IT Girls', a wonderful book about Lucy and her novelist sister Elinor Glyn, Lucy rented no. 17 from Sir George Dashwood. I presume we are talking about Sir George John Egerton Dashwood, sixth baronet of Kirtlington Park, 1851 - 1933. Apparently the house had been in the Dashwood family since the 18th century and probably was the family’s London residence. I do not yet know when the house was built but work on Hanover Square began in 1716 and Nicholls’ view of the north side of the square from 1754 suggests that it had been completed by this time. Our building seems to be no. 1 according to Horwood’s plan, and the chimney seen in Nicholls might suggest that it turned its back to the square.

Geraldine Edith Mitton remarked about Hanover Square in 1901: ‘A few of the old houses still remain, notably Nos. 17 and 23 …’ in 'Mayfair, Belgravia and Bayswater', edited by Walter Besant, part of the series 'The Fascination of London'. A few years later, in 1907, E. Beresford Chanceller recorded that no. 17 was ‘doomed to destruction’ in The History of the Squares of London. An auction of ‘valuable chimney pieces, Sheraton cabinets etc.’ took place at 17 Hanover Square on 28 April 1903. A catalogue for this sale is held in the archive of the other Dashwoods – of West Wycombe Park – who confusingly seem to also have lived at 28, Hanover Square, which I believe refers to the old 18 on the west side of the square. By this time, Lucy had moved on.

You can still see no. 17 now, and we haven't even started to talk about no. 23 yet. I'll leave you to hear about that story another day. In the meantime, enjoy one last photograph of no. 17. Can you see any ghosts, bowler-hatted, perhaps?

Love fashion? Subscribe to our fashion newsletter to read more stories from our collections, and see upcoming events and exhibitions.