Our City Now City Future season explored how modern cities can help expert makers flourish, and how London might maintain its skilled trades. The museum's new Curator of Making explores the rich history and threatened future of making in London.

Interior of the Coach-Wheelwright's Shop at 41/2 Marshall Street, Soho

Clare Atwood, 1897.

You might not think of London as a place where things are made. Sold, consumed, displayed – yes. London has always been a city of goods and things and objects. But made? Surely the process of making now happens far away, perhaps in a high-tech factory in China? And, historically? Didn’t early Londoners simply absorb the production of other places, bringing in French wines, Staffordshire pottery and Indian muslin for the gratification of their tastes?

London has long been a city of makers and making. The practice of particular trades and skills has defined – and continues to define – the city’s layout, in such a way that we can trace a spatial geography of London making by walking its streets and reading its maps. Certain forms of production and manufacture have tended to cluster together, populating parts of the city with complex webs of workshops and warehouses and wholesalers.

Wooden patten overshoe, 1711-20

Worn to protect shoes from the dirt of the street. ID no. A3635

Even today, the history of making can be traced through the names of streets and places in the city. The area around Eastcheap, once the principal area of the butchers’ trade, is a case in point. To the south, Pudding Lane gets its name from the ‘puddings’ of offal which would fall from the butchers’ carts as they made their way from Eastcheap to the river – nothing to do with our modern sweet puddings. To the north, on Rood Lane, the church of St Margaret Pattens gets its name from another trade practiced in the area from the 14th century: the production of pattens, or wooden overshoes.

From the medieval period, sites of making in London were dictated by a combination of practical concerns and the rules of the city’s livery companies, which governed important trades. Makers entered into mutually dependent relationships with other trades, including wholesalers, which affected their location. In the 15th and 16th centuries, for example, the production of baskets was focused around Eastcheap, due to the presence of the butchers, who needed baskets to transport meat. Another reason, however, was the nationality of many basket-weavers, many of them Flemish and Dutch immigrants. Ineligible to join a livery company or to settle where they pleased, they were legally restricted to the district known as Blanche Appleton, north of Eastcheap. This area therefore blossomed into a centre of basket-weaving.

Spitalfields woven silk court dress, 1752-53

Immigrant French weavers produced fashionable fabrics, creating neighbourhoods of makers like Spitalfields.

Immigration has always been an important factor shaping the city's landscape of trades, given that new arrivals to London tend to congregate together for reasons of language, religion and family connections. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the most significant group of immigrants were the Huguenots, French Protestants who were increasingly persecuted by the Catholic King Louis XIV.

Many Huguenots were skilled craftspeople, and the areas of London in which they settled became known for several specialised trades. In Spitalfields, master-weavers established a successful silk-weaving business. They built the tall terraced houses which still survive in the area, and which housed the looms that produced exquisite, innovative patterned silks for the fashionable denizens of London.

Their legacy survives in local street names, some of which were named after notable master-weavers – Fournier Street, Leman Street, Fleur de Lis Street. Somewhat misleadingly, Fashion Street has nothing to do with the silk trade, but is a corruption of Fossan, the name of the area’s original developers.

Watchcasemaker's chest of drawers, 1885-1910

Used at the Oliver family business in Clerkenwell, by four generations of the same family of makers. ID no. 86.417/272

Around Soho, meanwhile, the metal trades – including jewellery and watchmaking – flourished under Huguenot artisans, attracted to the area by the existence of a French church. The Harache family of goldsmiths had workshops on Old Compton Street, and Suffolk Street to the south, over several generations. The renowned silversmith Paul de Lamerie was based on Gerrard Street between 1738 and 1751; while the watchmaker Peter Debaufre worked on Church Street from 1686, the workshop continued by his son James until 1750.

By the second half of the 18th century, the clock and watchmaking trade had moved north to Holborn and Clerkenwell, with French and English makers alike settling around Red Lion Square and Clerkenwell Green. These included the great inventor John Harrison, who developed a timepiece which enabled the calculation of longitude while at sea. The advent of the horologists would set in motion several developments which turned Clerkenwell into London’s major centre of making in the nineteenth century. It ensured the presence of artisans with the ability to do precision work in metals, which, in turn, attracted jewellers and makers of scientific instruments to the area. This presence was augmented by the waves of Italian immigrants who settled in London between the 1820s and 1870s, many of whom were also skilled instrument makers – as well as glass blowers, carpenters, musical instrument makers and ice-cream makers, among other things.

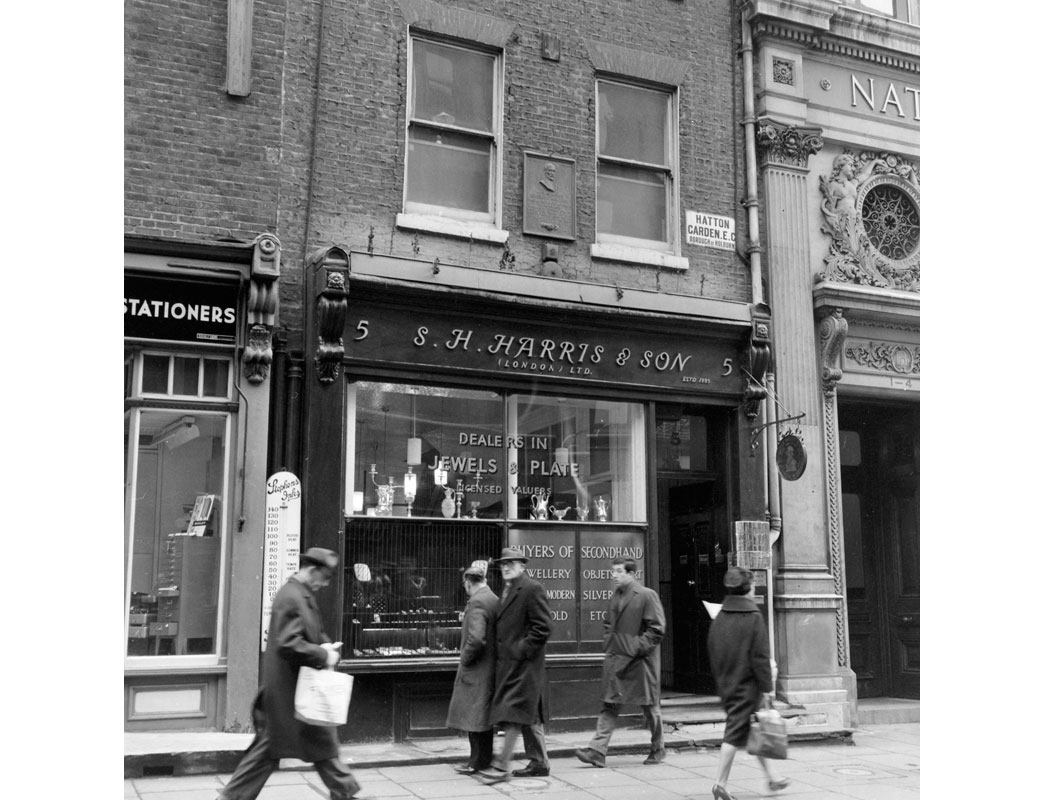

Hatton Garden, off Holborn, became the principal centre for jewellery-making in London, and remains so today. One of the first firms to set up in business there was the silver assaying office of Percival Johnson, in 1822. This developed into the global metallurgy and instrument firm Johnson and Matthey. The presence of jewellers went on to attract wholesale dealers in diamonds and other stones. Kosher eateries opened in the area, catering to the many dealers and artisans who were Jewish. Hatton Garden’s reputation as an international jewellery capital was cemented when De Beers, the biggest diamond company in the world, began to send its wares there for sorting and cutting in 1889. Other clusters of making have also grown dramatically in response to the arrival of one large and successful company – such as Tottenham Court Road, the importance of which as a centre for carpentry and furniture making in the 19th century was based on the arrival of Heal’s furniture workshop in 1818. Even today, numerous furniture retail chains, such as Habitat and DFS, retain a presence on the street around Heal’s, which is still going strong.

Not all historic centres of making survive. The area around St Paul’s Cathedral, particularly Paternoster Row, was once an international centre of publishing, printing, map-making and bookbinding. Originally the area was dominated by the monasteries associated with the cathedral, which produced religious and scholarly books. The district was given over to secular publishers during the Reformation, when the monasteries were dissolved by King Henry VIII. By the early 19th century ‘Paternoster Row’ was synonymous with the British publishing industry, and authors, critics and booksellers congregated in the coffee houses and taverns around there. The street was utterly obliterated during the Blitz, with millions of books burned. It was rebuilt as Paternoster Square, a series of anonymous office blocks, in the 1960s. Today it houses the London Stock Exchange and numerous food outlets for City workers.

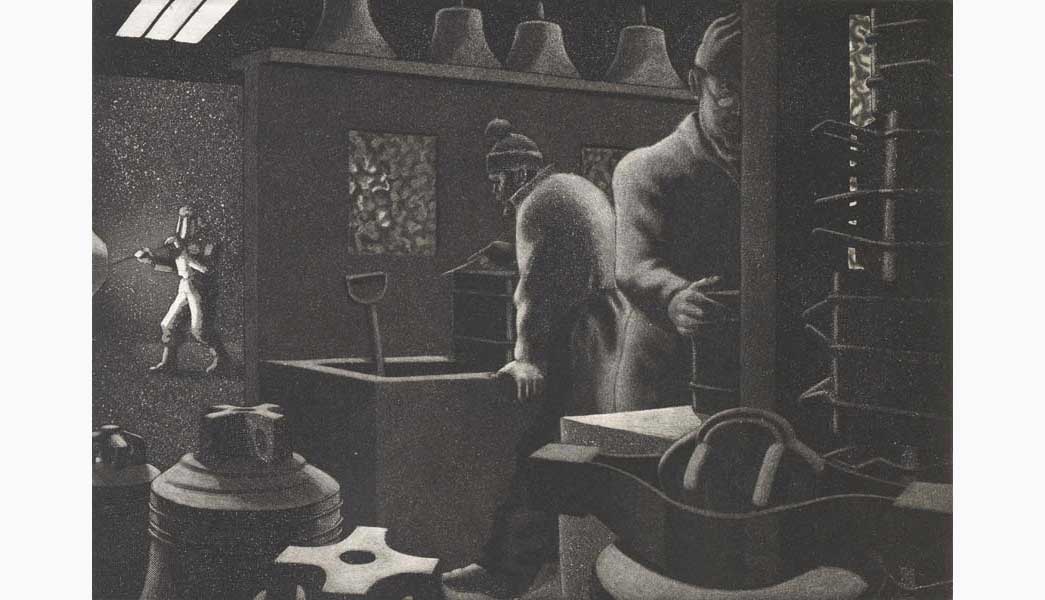

London, and London’s place in the global economy of making, has changed dramatically since the early 20th century. Some forms of making are thriving in London, particularly those associated with experimental technology. Clerkenwell and Shoreditch are now centres of innovation in digital design and 3D printing. However, hundreds of small factories and workshops have closed, forced out of business by cheaper imports, automated manufacturing, and rising rents. Making has not fled the city, and some traditional makers cling on. The Algha Works in Hackney are still making spectacles; and the Freed of London ballet shoe workshop isn’t going anywhere for now. The AB Foundry in Poplar casts large-scale sculptures for artists such as Anish Kapoor and Tracey Emin. Ince Umbrellas have been manufacturing in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green for over two hundred years.

These businesses have managed to adapt and survive, and London’s markets provide an outlet for hundreds of individual makers to develop their craft and sell their wares. East London in particular has seen a revival in markets and in maker-spaces, the latter often managed by charitable organisations such as Cockpit Arts, Craft Central and Bow Arts. Ironically, the cultural cachet of having makers living and working in an area is one of the drivers behind gentrification and rising property prices, eventually displacing the ceramicists, jewellers, textile designers and printmakers whose presence makes an area ‘cool’. London has always been a city of makers, and it remains so for now – but it’s at risk of being unmade.