One of the most notable – and notorious – features of London’s pleasure gardens was the masquerade, or fancy dress ball. They were also known as the ridotto, from the Venetian private gambling salons where visitors wore masks to conceal their identities. Wearing elaborate disguises, London’s rich, famous and infamous would meet to dance, flirt and intrigue until the early hours of the morning.

Masquerades were introduced to London by the Swiss count Johann Jacob Heidegger, who first came across them in Italy and originally staged them in London theatres. After Vauxhall Gardens opened to the paying public in 1729 (and, later, Ranelagh Gardens in 1741), they became the obvious venue for such lavish and fashionable entertainments. They were immediately popular among those who could afford the expensive tickets – often as much as one guinea, or a week’s earnings for a skilled labourer – or who could take advantage of the opportunity for disguise and sneak in. Masquerades were staged to celebrate significant public events, such as the end of a war or a royal birthday. In 1749, Vauxhall hosted a masquerade to mark the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which concluded the War of the Austrian Succession. Of this night, the gossipy politician Horace Walpole wrote that it was the ‘prettiest spectacle that I ever saw […] nothing in a fairy tale ever surpassed it’.

The return from a masquerade - a morning scene, 1784

A young lady dressed as a shepherdess with staff slumps in a sedan chair. Print by Robert Dighton and Carington Bowles.

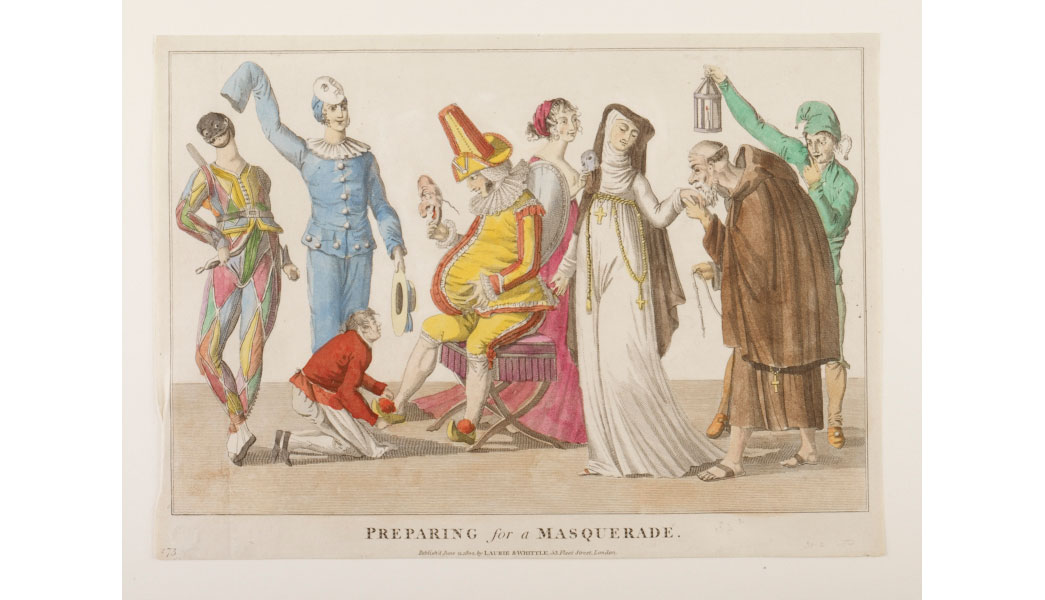

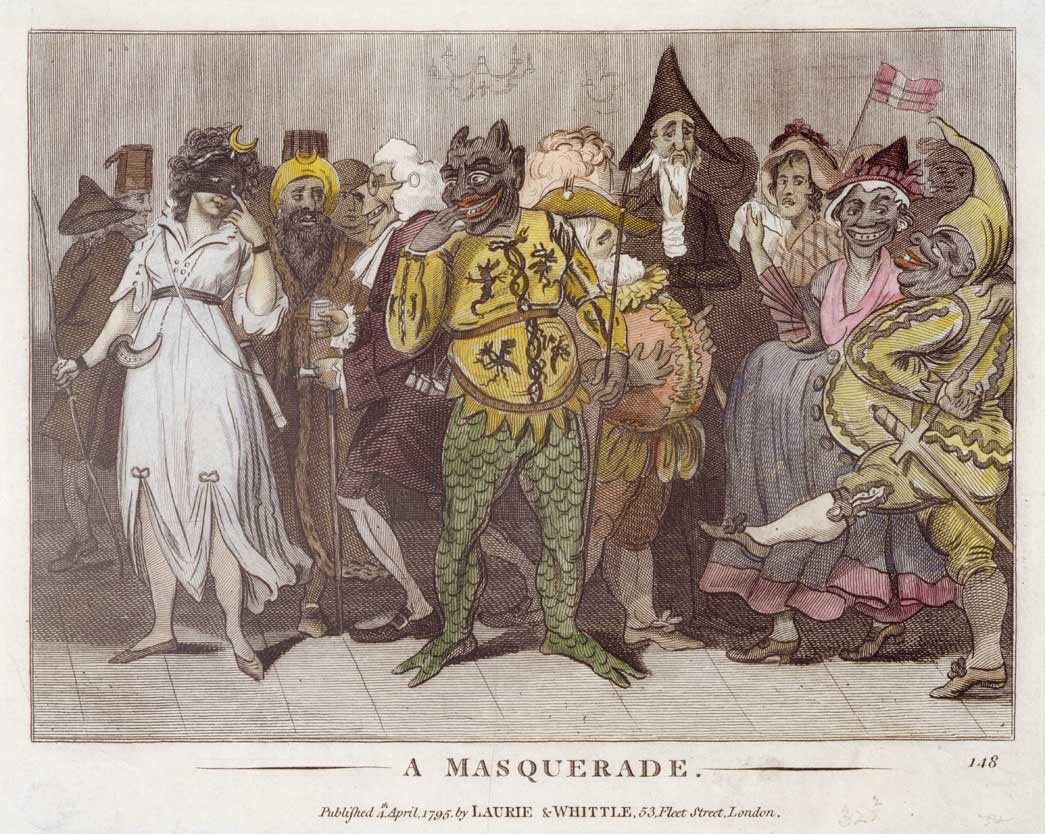

The costumes worn at masquerades were opulent, played on cultural references of the period, and were often ironic. Heroes and goddesses of classical antiquity were popular subjects, as were figures from the Italian commedia dell’arte, and allegorical costumes representing traits such as Virtue or Truth. National costumes of other nations, figures from folk songs and ballads, and even animal costumes were also frequently adopted.

Some guests simply wore a long cloak known as a domino, in black or white silk, their face mask serving as the sole mode of disguise. Traditionally, revellers would unmask at the end of the night – part of the fun was to try and guess which people occupied which disguises.

Despite their popularity and glamour, masquerades were seen by some as immoral, scandalous and unpatriotic. They were publicly denounced by Edward Gibson, the Bishop of London, who preached a sermon against them; while respected artists and novelists such as William Hogarth, Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson wrote in condemnation of them.

Masquerade costume, 1770-90

A black silk domino cloak with gold mask, worn over a french silk and linen dress c.1765. ID no. 70.59/1

What really sent critics into a panic was the idea of disguise, and the implications of being disguised. Within the walls of the masquerade, the formal conventions of polite eighteenth-century society were suspended. With the right costume, and a mask to hide your true identity, it was possible to step into another world for a few hours, where aristocrats played at being chimneysweeps and shepherds; men dressed as women and vice versa; prostitutes disguised themselves as nuns, and Englishmen became Ottoman Turks in robes and turbans.

Moralists and conservative thinkers worried that the norms which kept society functioning – social hierarchy, gender roles and so on – would be corrupted and compromised. What if, for example, a wealthy man became besotted with a prostitute in disguise? If a respectable woman showed off her body in men’s clothing? Or if impressionable young people regarded foreign cultures as glamorous, rather than inferior to the English? If status and respect could obtained – or lost – by simply pulling on some different clothes, wasn’t the entire social structure at risk?

In the end, the decline of masquerade’s popularity coincided with the increased public moralism of the early 19th century. Although ‘fancy dress balls’ remained a form of fashionable entertainment throughout the nineteenth century, they were respectable and harmless affairs compared with the risqué, dramatic masquerades of a hundred years before.

Part of our series about London's Pleasure Gardens, the pinnacle of nightlife in 18th and 19th century London. Read more about the Pleasure Gardens: costume; music; masquerades; eating and drinking; toilets.

First published during #RedressingPleasure – thank you for helping us to crowdfund our new gallery of 18th century fashion!