How a humble lead-weighted fishing net recovered from the river Thames can tell us about the history of London's river, fishing, and climate change.

In October 2018, students from Queen Mary University of London visited the Museum of London as part of their undergraduate course ‘Beer, Books and Longbows: The World of Medieval Objects’, taught by Dr Eyal Poleg, Senior Lecturer in Material History. Curator Meriel Jeater presented them with 25 medieval objects from the museum's stores about which little research had been done. Students chose their favourite artefact, researched it and wrote a detailed essay, exploring what it revealed about medieval life.

Climate change is immense and dangerous. The rise of the planet’s temperature, caused by the emission of greenhouse gases, is significantly impacting people and wildlife across the globe. In the medieval period, the planet’s temperature dropped, having a major impact on the natural environment. The effect of these environmental changes on medieval people and wildlife unfolds when we examine a 15th-century net sinker from the collections of the Museum of London.

In 1970 excavations of a coffer-dam in Blackfriars uncovered the wreckage of a 15th-century ship embedded in the Thames riverbed. Entangled in the wreckage were lead fishing net sinkers. The size and shape of these sinkers reveals them to be part of a medieval ‘Seine’ net: a net with heavier weights in its centre that allowed the ‘wings’ to be pulled together and entrap fish. The Seine net is one of the oldest nets used in rivers and estuaries. It was used by fishermen from boats as well as from riverbanks. The low quality of the weights suggests that it was not made as part of a wider manufacturing network, and reveals a time when large-scale fishing moved elsewhere. It evidences the move from river fishing to sea fishing caused by the ‘Little Ice Age’.

The 14th and 15th centuries were a time of great environmental turmoil for medieval Europeans. The ‘Little Ice Age’ stretched from 1350 to 1850. During this time the average temperature across the world dropped by approximately one degree Celsius. This greatly affected global ecosystems, causing large storms, known as storm surges, across the world’s oceans. Surges in the North Sea resulted in widespread flooding and riverbank damage across Europe, including in England and the Thames.

The Curfew Tower of Barking Abbey, the only surviving part of the medieval building

Photograph by Ron Baxter

The environmental changes caused by the ‘Little Ice Age’ had a great impact on the residents of medieval London, particularly in areas such as Barking and Swanscombe. People who lived along the Thames’ banks suffered from major floods. The lands of Barking Abbey, now close to London City Airport, were damaged by storms in the late-14th century. Due to the great expense of river bank and land repairs, the abbess (the head of the abbey) requested tax exemptions from King Richard II.

The environmental turmoil caused by the ‘Little Ice Age’ also had a very significant impact on the fishermen that lived and worked along Thames, whose riverbanks were damaged by the storms. Fish swam from the Thames onto the flooded farmlands, reducing the number of fish in the river and depleting fishing stocks.

Some fishermen took to illegal fishing on these flooded lands. In March 1489 residents of London sent a letter to King Henry VII asking for his support in the fight against poachers. The king granted their request. Many Thames fishermen were then forced to search further afield for their produce, leading to an increase in sea fishing. Evidence of this appears through the museum’s 15th-century net sinkers.

The net sinkers were likely made by hand, rolling lead around a rope or other fibre to create cylindrical weights. As this was not a particularly efficient or cheap method of production, they were unlikely made on a large scale. On the other hand, net sinkers required for sea-fishing nets, such as trawl and drift nets, were commonly mass-produced. These oval or triangular shaped weights were made using moulds that could produce several weights at a time. This was more efficient and cheap. The small-scale production of the net sinkers held in the Museum of London collection suggest a reduction in the number of Seine nets, perhaps indicating a move from river fishing to sea fishing influenced by the ‘Little Ice Age.’

The flooding of farmlands along the Thames transformed the food available in medieval London. City residents relied on the land surrounding London to provide agricultural produce. Wheat, barley and rye were grown there to be made into bread or ale. These grains made up 60-75% of the diets of all medieval people, regardless of wealth. Once the land had been flooded, many crops were destroyed, limiting the food available to the City’s residents. However, as the Thames’ fishermen headed to the sea, a greater variety of fish became available in the City’s medieval markets. This new diversity in fishing varieties was also encouraged by the free trade legislation put in place by King Edward III in 1335 that allowed foreign merchants to sell new and exotic fish in London’s markets.

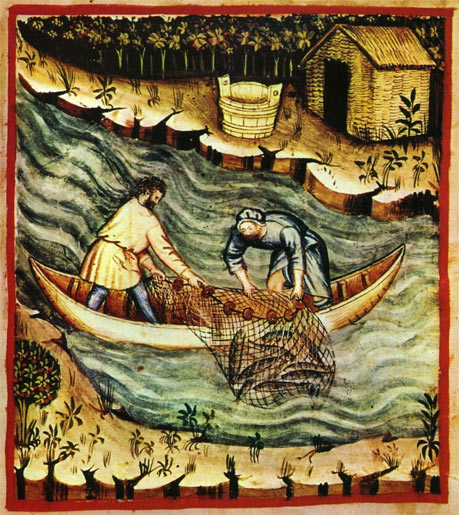

Medieval illustration of fishing, from Tacuinum Sanitatis, 15th century

Public domain image.

Simultaneously, other residents of the Thames’ bank took part in illegal activities. The abbess of Barking Abbey used part of the money saved from her tax exemptions to install illegal fishing traps in the river banks. These traps, known as weirs, forced fish down underwater tunnels where they were then captured and fed to livestock.

This led to significant outcry from the Thames’ fishermen. Court records show that the abbess was ordered to destroy the illegal weirs installed in her banks as they caught ‘young fish at improper times, before they be fit for food.’ This shows how some of the Thames’ fishermen blamed the abbess for the depletion in their fishing stocks.

Unlike today, nothing could be done to alter the natural climate change of the late-medieval and early-modern period. Thus the residents of London were forced to adapt to the changes in their surroundings in order to survive the environmental challenges of their age. Therefore these small net sinkers can shed light on the ways in which medieval fishermen adapted to the changes in the natural world caused by the ‘Little Ice Age.’