Francis Marshall, curator of the 2019 Beasts of London experience at the Museum of London, tells us the story behind the peregrine falcon with a fascinating history.

Beasts of London closed on 5 January 2020.

What links the fastest animal on the planet, a former Prime Minister and St Paul’s Cathedral? A taxidermic peregrine falcon in the Museum of London’s collection.

Peregrine falcons can hit 200 miles per hour when swooping in for dinner, which usually means a pigeon. Appropriately, this particular falcon was mounted in a gory tableau in the 2019 Beasts of London exhibition, standing on its avian prey's bloody remains. The pair are housed in a glass-fronted cabinet with a printed account of the falcon's history pasted on the back hall.

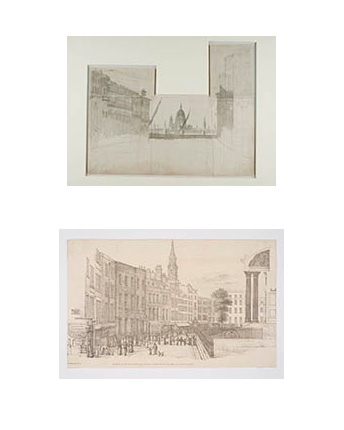

Two prints of St Paul's in the early 1800s

In 1834, the falcon made its home on the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, then one of the highest buildings in the city. After being shot in the leg, the bird was captured and kept in a cage by a Mr Pope, a wine merchant who ran The Crown in St Paul’s Churchyard.

In these confined circumstances, the peregrine lived ‘on royal fare’ for around a year and ‘thousands came to gaze upon him’. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the unfortunately fated animal died in the end.

St Paul's prints details (right)

Top: Unfinished view of St Paul's from Whitehall Place by Nugent, T., 1823, ref: A7316

Bottom: North Side of St Paul's Church Yard, with the end of Cheapside, Hornor, T., 1810-1830, ref: Z1489

The Peregrine falcon of St. Paul's, on display as part of Beasts of London

As the text in the case rather bombastically phrases it: ‘His soul, indignant at his shameful bondage, burst its proud tenement and fled to seek in loftier and noble regions, what above all else, it prized - Liberty.’ At this point Pope had the animal’s remains stuffed, where it served as a talking point and continued to attract patrons to his bar.

The stuffed bird arrived at the Museum in a circuitous way. It was initially given to the Natural History Museum by the Rt Hon Neville Chamberlain in 1939, then Prime Minister of a country on the brink of the Second World War. It’s unclear how Chamberlain came to acquire the bird himself, but after passing it onto the Natural History Museum, it came to the Museum of London in the 1960s.

Children and pigeons in Trafalgar Square, Henry Grant, 1972 - 1975

It seems the tail feathers are from a wood pigeon and, though we can’t be certain, the primary wing feathers are likely to be from a large domestic pigeon. A rather undignified end for such a charismatic bird of prey – although the pigeons might just see it as a form of poetic justice.

Although driven close to extinction during the 20th century, in the past twenty years, peregrine falcons have moved back to London. Today, there are around twenty breeding pairs of these raptors living in the middle of the city. If this seems unlikely, bear in mind that peregrines are birds of cliffs and mountains. They need a lofty vantage point from which to hunt.

Feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square, Henry Grant, 1954

Although we sometimes dismiss its urban environment as a concrete wasteland, London provides rocky cliffs aplenty in the form of tower blocks on which these birds can roost and nest. As a result, peregrines are now as at home in the city as the urban fox.

You probably wouldn’t expect to see the fastest animal on the planet living wild and free in central London. But watch out and you might just get a glimpse of one zooming overhead.