Our new display at the Museum of London Docklands tells the story of the Krios. This unique culture is descended from previously enslaved people who settled in Sierra Leone from 1787 to the late 19th century. We spoke to Melissa Bennett of the Museum of London and Iyamide Thomas, Historical Researcher of The Krios Dot Com, co-curators of the display.

Who are the Krios?

Melissa Bennett: The Krios are an ethnic group living in Sierra Leone, with a diaspora around the world including London. Krios (sometimes spelled Creoles) have a distinctive language and cultural traditions, reflecting that today’s Krios are the descendants of different groups of formerly enslaved people:

- Black Londoners who were re-settled to Sierra Leone in the 18th century

- ‘Maroons’, free black inhabitants of Jamaica who had fought against the British

- ‘Black Loyalists’, freed slaves who had fought for the British during the American Revolution

- Africans who were liberated from illegal trans-Atlantic slave ships by the Royal Navy

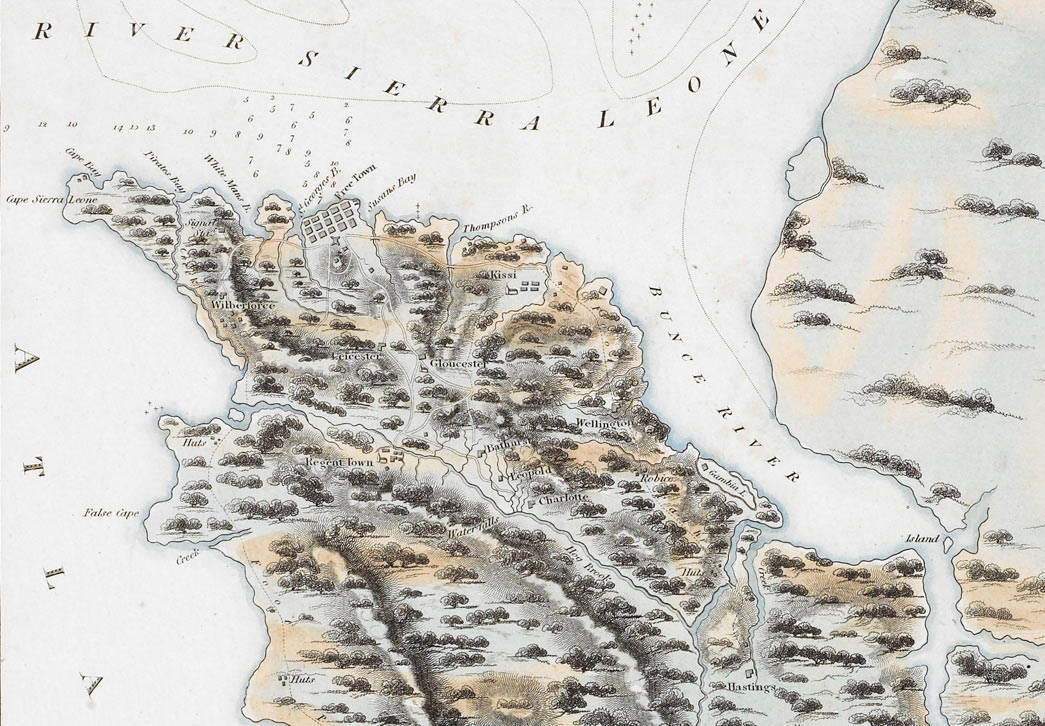

These four groups, settled by the British around the newly created 'Province of Freedom' from 1787 onwards, came together to create a unique society. They came from London, Nova Scotia and the coast of Africa. Some had fought for Britain in America, others had rebelled against the British in Jamaica.

Iyamide Thomas inspects a Krio dress before its display at the Museum of London Docklands

Iyamide Thomas: The display shows how all these different people from different parts of the world came together to create Krio culture. These people had very little to unite them, not even a language in common. They were all put into this melting pot of Freetown, and told to get on with it — which for the most part they did. It’s extraordinary there weren’t more disputes.

I’m Krio, and I’ve been involved in heritage groups since 2011. In 2016 a small group of us created TheKrios.com to help educate and provide a resource for people interested in Krio history and heritage. It’s fascinating how closely interlinked the Krio culture is with British history: from the slave trade, to abolition, and resettlement in the ‘Province of Freedom’.

What was the inspiration for this display?

Iyamide: A lot of people have heard of Sierra Leone, but in a very negative light: they’ve either heard of Ebola or the civil war. I wanted to show another perspective on Sierra Leone. That’s the unique history and culture of the Krios.

One of the features is our display of notable Krios through history, people who excelled in fields from medicine to theatre — several of them the direct descendants of Liberated Africans. People like Samuel Crowther, the first African bishop of the Anglican Church: he had been kidnapped and enslaved himself. These are people who are really caught up in the legacy of slavery. We recognise our culture came out of that wicked thing, but in Sierra Leone, it managed to create some good from bad.

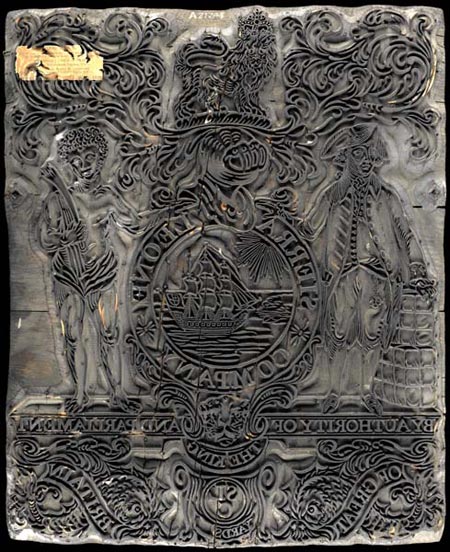

Tillet block, c. 1800

Melissa Bennett: We’re displaying it in our London, Sugar and Slavery gallery, where exhibits focus on the legacy of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The Krios are obviously strongly connected to that legacy, but also to East London where the museum is based.

There are a surprising number of objects in the Museum of London’s collection that relate to the Krio people, and the history of Sierra Leone when it was a British colony. We’ve been able to put many of them on display for the first time.

They range from the simple: a wooden block which bears the crest of the Sierra Leone Company, a British organisation that founded the first colony in Sierra Leone in 1792. It was used to stamp the coarse tillet cloth that was the main export. Then there’s the dramatic: like a magnificent silver dish that was a gift to Thomas Cole. He was the Superintendent of Liberated Africans, so he was in charge of sorting out where the people newly freed from enslavement would end up.

Iyamide: When I first saw this dish, I thought it was beautiful, but as I learned more about the Liberated Africans I started to wonder why he’d been given this. Why were they glorifying him, given how the Liberated Africans were sometimes treated?

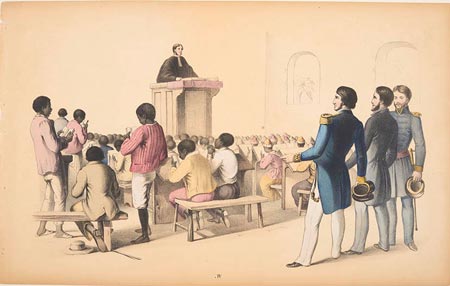

Military officers and church congregation of Liberated Africans in Sierra Leone

Who were the Liberated Africans?

Melissa: They were one of the largest groups of people who made up the Krio population. After the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the British began to patrol the Atlantic Ocean to try and stop the traffic in enslaved Africans. When the Royal Navy captured an illegal slave ship, they would bring the vessel and the enslaved people aboard back to Freetown. Then the British would try to recruit these newly liberated people: they wanted them to sign up as soldiers in the West India regiments, or as apprentices for much-needed jobs in the colony.

Was it a transition from one slavery into another?

Melissa: I wouldn’t go that far — but apprentices would be bound for up to 14 years, and they often didn’t know the terms of their contract. These enslaved people would be held in a huge yard in Freetown and military and apprenticeship recruiters would come in, with African interpreters, and try to trick or coerce them into joining up for service which they didn’t understand. It’s the darker side of ‘Freetown’. The display tells these historical stories, but it also is filled with objects from the thriving Krio diaspora.

What are some of those objects?

Iyamide: You have these ‘Bod Os’ – you don’t see them anywhere else in West Africa. These are colourful, sometimes two-storey wooden houses, which are very similar to the houses you see on the east coast of America. This is the legacy of the Nova Scotian connection, of enslaved people who fought for the British against the American revolutionaries. They were promised their freedom, but after the British lost the war, they moved these ‘Black Loyalists’ to Nova Scotia, in Canada.

Melissa: They didn’t like it much, and one of their number, Thomas Peters, travelled to London to ask for resettlement for his people. So they were sent to Sierra Leone, to reinforce the struggling colony there. They took the design of the ‘Bod Os’ with them.

Iyamide: On display we also have a bible in the Krio language. You have the language Krio- this is still the main language spoken in Sierra Leone today. It is a mix of all the different influences of Krio culture, including European traders who came to deal on the African coast- Portuguese, French. There’s also a lot of Yoruba. The largest ethnic group among the Liberated Africans were Yoruba- my name is Yoruba, so you have Krios with African names and European names. You see the same fusion in our traditional clothes.

What’s your favourite thing in the Krios display?

Melissa: The traditional Krios dress is my favourite object because it’s bright and colourful and illustrates the mixing of all these different cultures in a really visual way. We’ve also never had a dress on display in this gallery before: it’s wonderful to have some variety in the kinds of objects on show.

Iyamide: The dress: I provided it, my sister-in-law made it in Freetown, especially to go on display in the museum. It’s a little old-fashioned, so I don’t usually wear this version of the costume. But with the resurgence of groups promoting Krio culture, you have the younger people starting to wear them. You can see how it mixes the Victorian influences with colourful African fabrics and little touches from America and Jamaica. It's like the story of the Krios in fabric.

The Krios is on display from 27 September 2019 at the Museum of London Docklands.