Some of the oldest human remains ever recovered from the River Thames were recently found by a mudlark searching the foreshore. What was life like for this Neolithic Londoner, and how did his body end up first in the Thames, and now at the Museum of London?

A Neolithic crime scene?

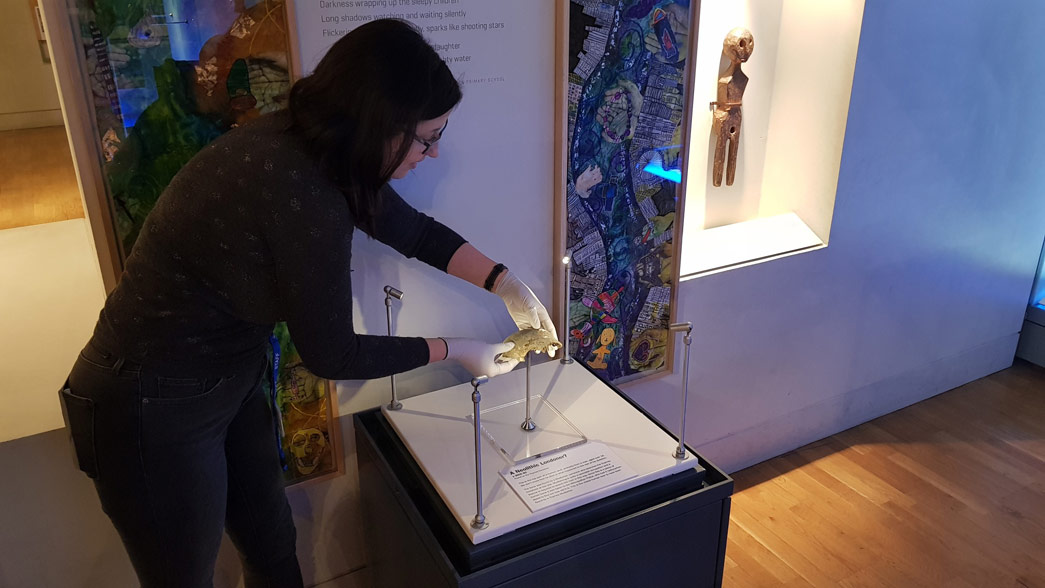

Dr. Rebecca Redfern, human osteologist, holds the skull fragment

Expert in the study of human bones

The concerned mudlark who discovered this skull at first contacted the Metropolitan Police. Naturally, in the case of human remains discovered in the city, they had to investigate.

DC Matt Morse explained: "Upon reports of a human skull fragment having been found along the Thames foreshore, Detectives from South West CID attended the scene. Not knowing how old this fragment was, a full and thorough investigation took place, including further, detailed searches of the foreshore.

The investigation culminated in the radiocarbon dating of the skull fragment, which revealed it to be likely belonging to the Neolithic Era. Having made this discovery, we linked in with the Museum of London who were more than happy to accept the remain."

The police's dating showed the skull to be about 5600 years old, or 3600 BC, during the Neolithic Period. This "New Stone Age" began about 6,000 years ago, with the development of farming. It ended in northern Europe as the use of metals became common, moving Britain into the Bronze Age in about 2000 BC.

A very different London

Living in the area that would one day become London, this Neolithic man would have seen a very different landscape than we are used to. The Thames was much wider and shallower than it is today, and bordered by extensive mudflats and deciduous woodland. Traces of human activity dating to between 3500 and 4000 BC have been found along the floodplain of the Thames, mainly in the form of flint tools and weapons or fragments of pottery vessels.

The humans living in the future site of London lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle of herding, supplemented by hunting and gathering, and increasingly, more settled agriculture. A rare survival of this more rooted lifestyle was found at Runnymede Bridge. Here are the remains of at least one large rectangular timber house, erected near the river between 3900 and 3500 BC, the same period as the skull dates to. The area around the house contained cattle bones, broken pottery, and discarded flint tools. People living in these houses were probably extended family groups who also undertook limited crop production. Burnt grain has been found at a site near Canning Town dating to between 3900 and 3300 BC.

Rescued from the river

Selection of stone axeheads and maceheads found in the River Thames

Made from a mix of rare materials not native to the Thames Valley. Their finely polished surfaces and perfect condition indicate they were never used, but probably thrown into the water as offerings to the river deity.

How did this Neolithic man's body end up in the River Thames, washed onto the foreshore over five thousand years after his death?

The Thames at the time provided a wide range of natural resources as well as being an artery of communication and transportation. Increasingly, Neolithic people seem to have seen the Thames as a sacred river, perhaps similar to the Ganges in India. Offerings to the Thames's waters included human remains, pots, bone and antler tools, as well as many of flint and stone axes.

The largest and most beautiful axes and maces, often made from rare, exotic stones and some traded from as far away as Ireland, Cornwall, and mainland Europe, seem to have been deliberately chosen as gifts to the spirits of the river. Could this Neolithic man's body have been another offering to the sacred river?

Of course, it could be a coincidence: the changing course of the river and its tributaries washed over many early settlements, doubtless sweeping away Neolithic graves.

However he found his way to the water, this ancient skull now serves as a reminder of the long, long history of humanity in the London area.

Dr. Rebecca Redfern, Curator of Human Osteology said: "This is an incredibly significant find and we’re so excited to be able to showcase it at the Museum of London. The Thames is such a rich source of archaeology for us and we are constantly learning from the finds that wash up on the foreshore.

We are grateful to the Metropolitan Police for their collaboration with us on this and are eager to welcome visitors to see this new discovery.”