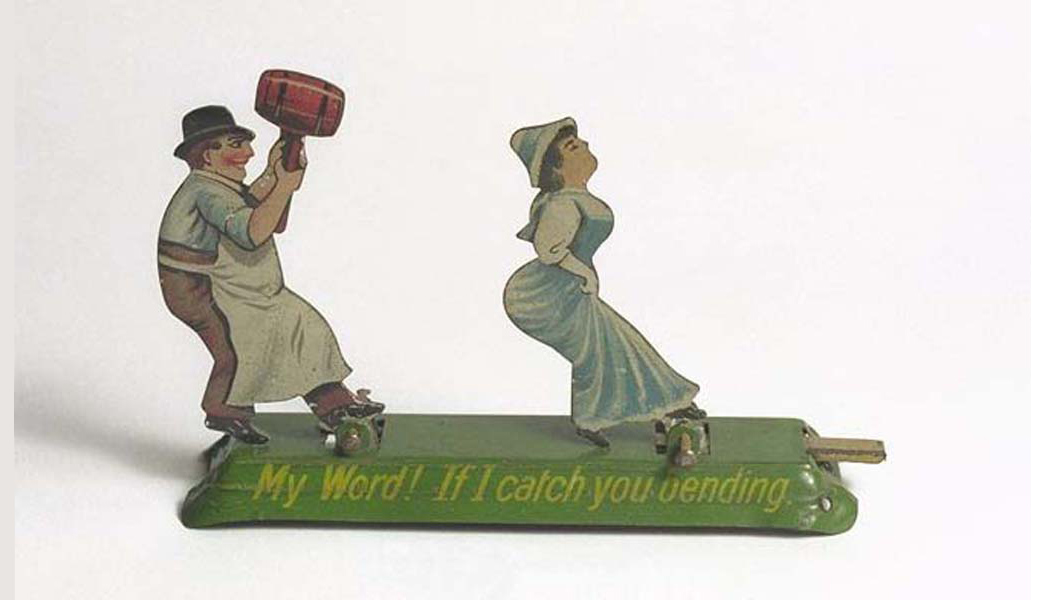

Over Christmas, we look at a selection of Christmassy items from our collection, ranging from a magnificent ballet dress once worn by Anna Pavlova, to some humble tinplate toys. Every one of these toys was imported from Germany and sold on London’s streets for a single penny in the early years of the 20th century.

The penny toys are a small part of a large collection of penny toys and novelties donated to the Museum of London in 1918 by Ernest King. Ernest worked as a Company Director for the straw hat maker Melch and Sons. Based at the firm’s headquarters in Gutter Lane, he was well placed to observe the activities of the numerous ‘gutter merchants’ trading in the nearby St Paul’s and Ludgate Circus area. Between 1893 and 1918 King purchased over 1500 items from the street traders, and in 1918 donated his collection to the museum. He also gave us two notebooks listing all the objects and their date of purchase, and a scrapbook filled with news cuttings reporting the plight of the street sellers.

Toy clown and dog penny toy

The mass production of toys and novelties from the last quarter of the 19th century enabled all but the poorest Londoners to buy penny Christmas gifts for their children. Whilst the tinplate toys were the Christmas ‘bestseller’ for the street traders, Ernest purchased throughout the year. His collection therefore offers a unique insight into the history of London at a period of great social change.

Here was a man with no museum background who understood the relevance of collecting contemporary social history at a time when such a discipline was largely unheard of. His collection covers a range of subjects from politics and war through to royal memorabilia and popular culture. He was methodical in his collecting and his dating of every purchase enables us to chart the interests, concerns and popular trends affecting Londoners and London at a very specific moment in time.

Rather frustratingly, when Ernest offered his collection to the museum it appears my predecessors failed to document any further information about the collector or his collection. However, I believe his scrapbook of news cuttings detailing the plight of the ‘gutter merchants’ may offer a clue to his intentions. Casual street sellers were some of London’s poorest citizens. At Christmas their ranks were swelled by children, the disabled and elderly desperate to benefit from the growing commercialisation of Christmas. London’s poor were notoriously resourceful and wasted no opportunity to ‘turn a penny on the streets’.

Within a few years of Ernest starting his collection, the great social investigator Charles Booth issued his first survey of London’s poor that identified street sellers as being among the poorest of the capital’s workers. Classed alongside loafers, criminals and semi-criminals, the occasional street sellers lived the ‘life of savages, with vicissitudes of extreme hardship and their only luxury is drink.’ Experiencing ‘an appalling amount of poverty and discomfort’ they were often found to be living in licensed common lodging houses and casual wards.

Not only is Ernest’s collection a great documentary of street life in the late Victorian and Edwardian period, it also represents the desperation of those who had no welfare state to depend on. As a social history curator, I hugely appreciate Ernest’s skill as a collector. But I also like to think his wonderful collection remains a legacy of his concern for the street sellers he supported for 25 years.