The Museum of London recently added 18 video games to its collections. We asked digital curator Foteini Aravani how she chose these games, why it’s so hard (but so important) to let people play them, and why she’s a video game voyeur.

Why did you choose these games in particular to include in the permanent collection?

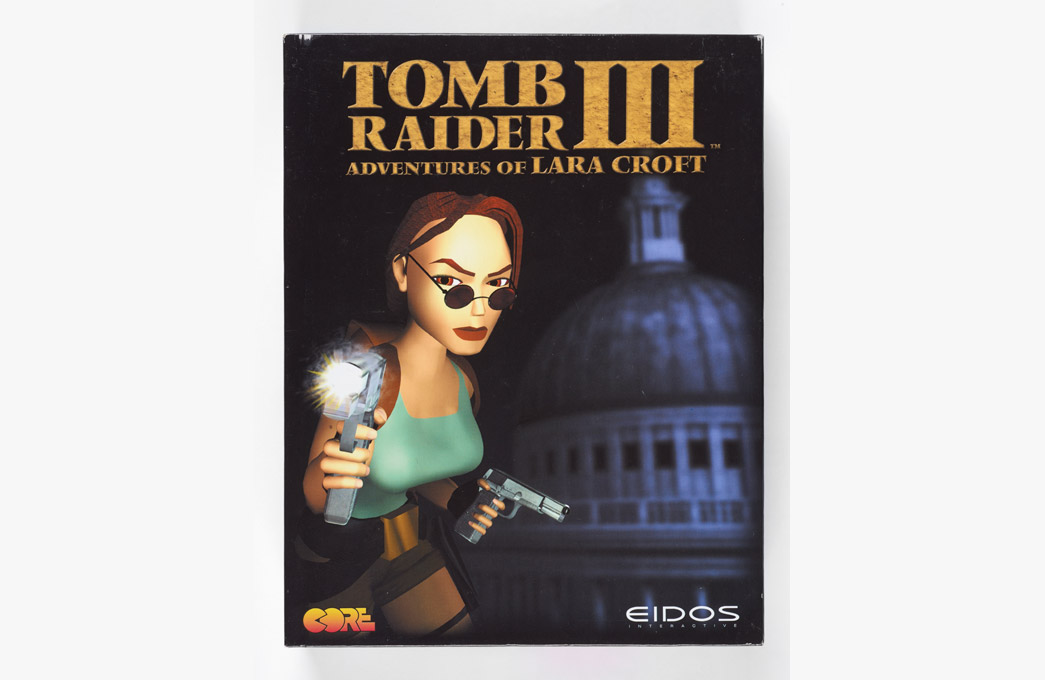

All of the games chosen were ones that either depicted (or misrepresented) London, or were developed and programmed by Londoners. I decided on a rough cut-off date of 2000, just before the release of the Playstation 2, which is still the most popular console of all time. As part of our new digital collecting framework, we wanted to catalogue the digital history of the city, and these games are the landmarks of the early period in London games.

One example would be Sensible Software, a software development company that was active in the 1990s. The highlight of their career was a game called Sensible World of Soccer. That was selected by Stanford University in 2007 as one of the ten most important video games of all time.

I have to confess, I’ve never heard of it.

No, I hadn’t either, before I began this research. But it is a part of the city’s history, and now it is part of the Museum of London’s collection. We have also collected games that have become iconic series, such as the Tomb Raider games.

(The Stanford top 10 list included titles like Tetris, SimCity and Doom, which pioneered whole genres of modern gaming. Sensible World of Soccer (1994) was one of the first to combine a computer football game with a comprehensive manager mode where you could select and trade players, paving the way for franchises like FIFA Soccer, one of the most popular video games in the world.)

What are the challenges of collecting games?

Video games are more prone than other media to obsolescence. With each new generation of hardware and software, scores of titles are made unplayable. Without a strong commercial incentive to maintain their back catalogues, many publishers allow games to drift into extinction. When companies such as Nintendo do put old titles back on the market, the re-releases are limited to a handful of well-known classics, placed in the company’s digital store for unceremonious download.

We are a social history museum, and we treat the video game collections as museum objects in the same way we treat our collections of, for example, London trade tools. We preserve copies of the original game, with the hardware that would be needed to play them.

But don’t these video games suffer deterioration over time?

Yes, of course. The ZX Spectrum games we have collected (like Hampstead) are stored on magnetic tapes. (ZX Spectrum software was distributed on audio cassette tapes.) Those tapes deteriorate over time, the plastic decays and the data on them – the game – is lost. Some of the original games we have collected are already unplayable.

So you’re just collecting cassette tapes? With dead games inside them?

The tapes were still alive - that is, the data was still retrievable - when we added the games to our collection. We have now managed to digitise the source code, the content, to preserve the game. Because if these tapes are not already dead, they will die with mathematical precision in the near future!

The actual cassette can no longer be played, but for reasons of historical record and provenance we keep the original. We keep the original packaging, any guidebooks or manuals that came with the game, to retain, as far as possible, the experience of people who first bought and played with these games. But of course, we also focus on keeping a playable version of the game, via various forms of emulation and preserving the source code. Just because you cannot plug a game into the original console, it does not mean you cannot play it.

We want all the games in our collection to be playable, not just historical objects. I would never create any exhibition of video games that just sat behind a glass case, that you could not interact with. Video games are about playability, interaction, immersion in a virtual world. If you cannot do that, there is no point.

So how do you let people continue to play these games?

Well, video games and their systems are unique because they are totally interdependent, everything must work together, to let you experience them. Games rely on hardware, software and input/output devices, screens and joysticks, all coming together to perform correctly. We were really focused on capturing not just the mechanics of the game, or how it looks, but the original experience of playing. So we extract the source code of the game, and run it on a small, very simple computer called a Raspberry Pi, but we keep all the original devices. With the games originally released for the ZX Spectrum, you play the game with the Spectrum keyboard, and you see exactly the image and the design you would have seen thirty years ago, but you are playing an emulated copy of the game.

How is emulation different from the original?

Emulation interprets game software from obsolete video game systems on modern computers, which will often make small modifications to the source code. As a museum we very carefully track the differences, and which emulator provides the experience most similar to the original. That record – the metadata- is stored alongside the collected hardware and software, so that future curators can keep these games playable. Over time, the emulated version will itself deteriorate and become obsolete.

So will you eventually need to build an emulator to simulate playing a ZX Spectrum emulated on a Raspberry Pi? And then an emulator emulator emulator…

Perhaps in the future! But this is very early days. At the moment we use an open source programme called the RetroPi Emulator, developed for free by volunteers. That means it receives constant updates from the community, and also platform independence – it does not rely on one piece of hardware that you can only buy from one company. Oddly, it is more sustainable to rely on private passion than on a corporate solution. The developers have also been hugely generous, with about half the games in this collection being donated by people who worked on the games or their studios.

Why are you so keen to mimic the original hardware? The ZX Spectrum keyboard, and so on.

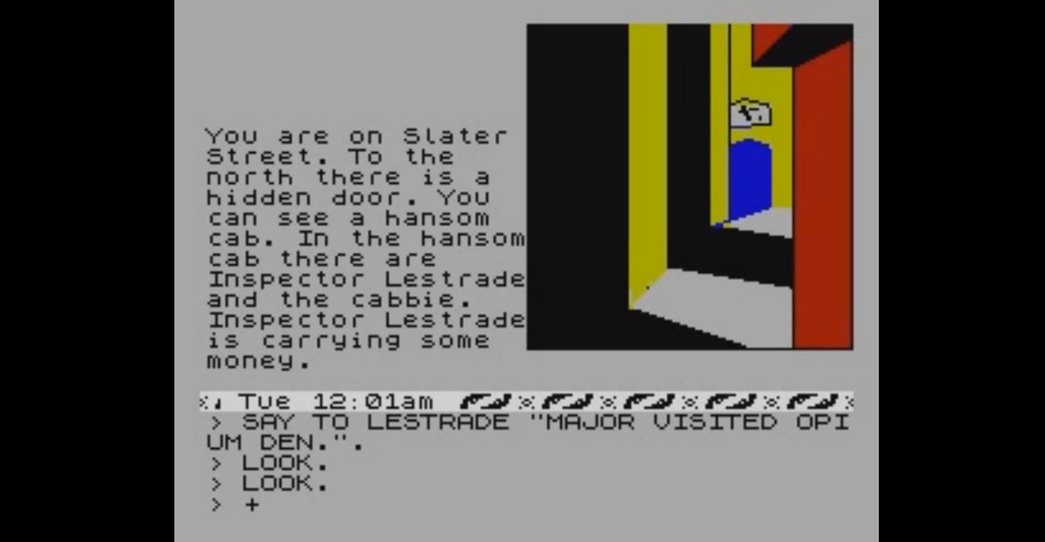

If you look at other museum projects to collect video games, you will see people like MOMA (the Museum of Modern Art in New York) who are interested in the design, the aesthetics of games. They are driven by what Pacman or Tetris looks like. But we care about the video game as a cultural artefact, about why it was created, who made it and the context of the time. For this reason we collect also oral histories of interviews with the developers, concept art, promotional material, and so on. I just love that a game like Hampstead reflects the charged political climate of the 1980’s, that it is a game created at the height of Thatcherism, and it embeds all of these subversive contemporary attitudes. The video game is a window into a moment in social history.

(In Hampstead, living in the titular suburb is the end goal, and is presented, in the words of one of the game’s writers, “as a sort of quasi-religious goal; a social and cultural nirvana.”)

That social history includes the act of playing the game?

Yes. I am not a gamer myself- well, perhaps a few games of Tetris– but I am fascinated by the experience of playing games, and what it reveals about people. I watched a father and son looking at the games in our Show Space display, and the dad was saying that these text-based adventures were what I used to play at your age. The son was somewhere between contempt and disbelief, I think. But the son tried to play, and he couldn’t even begin- you need this very specialised vocabulary for older adventure games.

The computer can only recognise very specific commands? Like “Go north”?

Yes, or “Get clothes”, that kind of thing. But then the father sat down to play and he knew all the commands, the magic words, immediately. It was this specific mindset that you needed to immerse yourself in. The father had not played for at least twenty years, but he had still had the world of the game hidden away in his mind. I have an almost voyeuristic fascination with the effect video games have on people.

What’s next for the video game collection?

I really want to find the absolute first video game to ever depict London, and also the first video game developed by a Londoner (which might of course be the same game).

If you have any suggestions about games that the Museum of London could collect in the future, or would like to share you own stories of classic video games, please get in touch.