The stories of women are often less well documented than the stories of men, and this is true of life in Roman London. Senior Curator Francis Grew turns to an unusual source – Roman tomb monuments – to tell us more about Londinium’s female residents.

‘Was this Rome’s man in London?’, ran the headline in the Evening Standard one day in March 1999. Archaeologists had just made the sensational discovery at Spitalfields of an intact Roman stone sarcophagus, with decorated lead coffin within. The conclusion that this was the grave of a high-ranking man was all too obvious. But once the coffin had been opened, the deceased turned out to be a young woman. Richly arrayed in gold-threaded robes, she had come to London from the Mediterranean.

These events prompted me to look at other Roman lead coffins that had been found with skeletons inside. There were 243 from Britain at that time. In many cases, the bones were too degraded for analysis, but I was surprised to find that as many as a third of the remainder were of children. Even more of a surprise was that two thirds of the adults were female rather than male. The Spitalfields Woman was far from exceptional. In Roman Britain, a woman was more likely than a man to be given a high-status burial in a lead coffin.

Who were these women? What lives had they led that resulted in such expenditure on their funerals? One day we may discover a writing tablet from Londinium on which we can read the thoughts of a woman in her own words, perhaps even written in her own hand. But in the meantime, we can read between the lines of the available evidence to learn more about the women of Roman London.

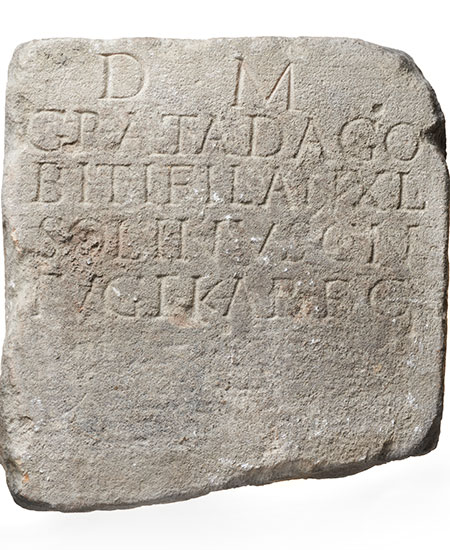

Gravestone of Grata

Translation: ‘To the spirits of the departed. Grata, daughter of Dagobitus, aged 40 years. Solinus had this made for his dearest wife.’

From their grave monuments or sarcophagi, at least we know their names: Claudia Martina, Grata, Atia, Marciana. They lived at very different times: Grata perhaps as early as 100 CE, Claudia somewhere between 100 and 200, Marciana around 250, Atia as late as 300-350. In three instances we know how old they were when they died. Grata was 40, Claudia 19, Marciana just ten.

The monuments give us no details about how they lived. But do they tell us how other people felt about them? Marciana’s father hoped the memory of his daughter would survive in perpetuity (‘memoriae perpetuitati’). To Grata’s husband, she was ‘dearest’ (‘karissimae’). In the eyes of the dedicator, perhaps her father, Atia was not only ‘dearest’ (‘carissimae’) but ‘deserving’ (‘meritis eius’).

Images of Atia and Marciana appear on their monuments, both in the form of head-and-shoulders busts. But can they fairly be described as ‘portraits’? Both wear similar tunics. Marciana’s is entirely stylised, while Atia’s is more fully modelled with heavy folds; she draws it across her chest with her right hand, exposing her index and middle fingers. Marciana’s face is crudely delineated, her hair neatly arranged in waves on either side of a central parting – a hair-style made fashionable by empresses of the period 200-250 CE. Of Atia’s features, however, there is nothing. Not as a result of subsequent damage but because her head was never more than roughly blocked out. Why so?

Sarcophagus of Atia

Translation: ‘From Gaius Etruscus to his dearest and deserving Atia’

Marble sarcophagi, such as Atia’s, were manufactured in large numbers, in relatively few patterns. These costly monuments were shipped worldwide from marble yards around the Mediterranean in a near-finished state, leaving only a few specific details such as names or facial features to be added by the purchaser. In 4th-century London there were probably no stonemasons with the skills needed to personalise a sarcophagus.

If these are not life portraits but conventional images, can the same be said about the words on funerary monuments? By not taking the monuments at face value, we discover something of the stories that lie behind the carefully chosen text. Consider the word ‘pientissima’, which Claudia Martina’s husband applies to his wife. Meaning ‘most dutiful’, it reappears on another monument from London, this time the tombstone of a man, a deceased legionary centurion. Ianuaria Martina, his wife, had the monument made in his honour, perhaps following instructions in his will.

Describing her as ‘coniunx pientissima’ (‘most dutiful wife’) seems too appropriate to be questioned. Until, that is, we come upon so many instances of its usage that it begins to seem formulaic. Other ‘pientissimae uxores’ (‘dutiful wives’) include Flavia Peregrina from Rotherham, Yorkshire, and the wife of Marcus Aurelius Nepos from Chester. The latter’s marital status is recorded but not her name.

Hexagonal altar-cum-statue base of Claudia Martina

Translation: ‘To the spirits of the departed and of Claudia Martina, aged 19 years. Anencletus, a provincial, dedicated this to his most dutiful wife. She lies here.’

There is often an uncomfortable ambiguity about funerals and funerary monuments. They can be more about the living than the dead, a chance to showcase a family’s achievements to a captive audience. This could be the case with the dedications to women from Roman London. None of them came from an ‘ordinary’ family, each had something exceptional to celebrate.

Take Grata (the Latin equivalent of ‘Grace’ or maybe ‘Cheryl’). Her father’s name – ‘Dagobitus’ – betrays the fact that she was of British heritage, almost certainly born here. To commission a gravestone in proper Roman style, with good syntax and phraseology, was proof that her family had ‘made it’ in Londinium.

Or what about Marciana? Her father’s name – Aurelius – suggests that the family had only recently become Roman citizens, probably in 212 CE when the emperor Caracalla gave that status to all free-born people in the Empire. This Aurelius, moreover, seems not to have been a Londoner. Regrettably damaged at a crucial point, it has been suggested that the stone recorded his service as a magistrate in a city beyond London.

Gravestone of Marciana

Translation: ‘To the spirits of the departed and to the everlasting memory of Marciana. She lived ten years. Aurelius, decurion, had this made.’

Atia’s sarcophagus is the only monument to have been found outside the city walls. It came to light in 1867 in Lower Clapton (Hackney), and presumably came from a family mausoleum on the banks of the river Lea. The dedicator was Gaius Etruscus, his name clearly alluding to the people who once inhabited central Italy. But as a personal name in the 4th century CE, it is exceptionally unusual. Dare we picture a doting but antiquarian relative, intent on bringing Roman tradition to London through the medium of a loved one’s death and burial?

Arguably the most intriguing case is that of Claudia Martina. Though she was a full Roman citizen, her husband had been enslaved and given the name Anencletus (Greek for ‘No complaints’). Anencletus’s life, however, was not that of most enslaved people. Working in a branch of the Imperial Household based in London, he likely earned a decent wage. His short-lived marriage must have been a huge achievement, denoting a real, though probably ambiguous, acceptance into Roman society. It is something he will have been keen to memorialise.

So from rich Mediterranean girl in a gold-threaded robe to spouse of an Imperial slave, we see that the females of Roman London have left their mark. But sometimes we must dig very deep and look not only at words but at their arrangement, if we are truly to read between the lines. The great tomb of the procurator, Julius Classicianus, was found on Tower Hill and has been reconstructed in the British Museum. What are the largest and most prominent letters on its dedicatory tablet? Not the man’s name but four huge characters spaced out on the bottom line: U X O R – his WIFE. That wife was Julia Pacata, daughter of Julius Indus, proud chieftain from the Trier region. He had raised a cavalry regiment to fight for the Romans against his Gallic neighbours in the revolt of 21 CE.

Let us close by picturing Julia as a formidable woman, married to an aspiring Gallo-Roman aristocrat, fully aware of what she had contributed to her husband’s career. In Julia, perhaps, we at last find a woman speaking in her own voice.