The Walbrook, one of the lost rivers flowing beneath London's streets, is a time capsule of Roman Londinium. For over 170 years, archaeologists have dug astonishingly well-preserved artefacts of the ancient city out of the waterlogged earth of the stream. A 2017 display at the Museum of London, Working the Walbrook, used this collection of tools and other everyday objects to examine what life was like for ordinary Roman Britons. Let's hear from Owen Humphreys, whose research underpins the display.

Most of us can sum up our working lives in a single object. I’m writing this on one right now: the best laptop I could afford on a student income, light enough to carry between libraries, keys grubby from typing whilst handling muddy artefacts. Perhaps yours is a sleek high-end machine, built to impress clients as you show them an animated walkthrough of their new low-impact eco-kitchenette. Perhaps it’s a bulky machine overloaded with corporate encryption software, just small enough to use on a tube seat, or an ageing desktop buried beneath layers of family photographs. They may not always be glamorous, but for many people these machines embody our everyday lives. They are the tools with which we earn our bread and create our professional identities. The same was true for people living almost two thousand years ago, in the Roman city of Londinium - but of course, their tools were rather different.

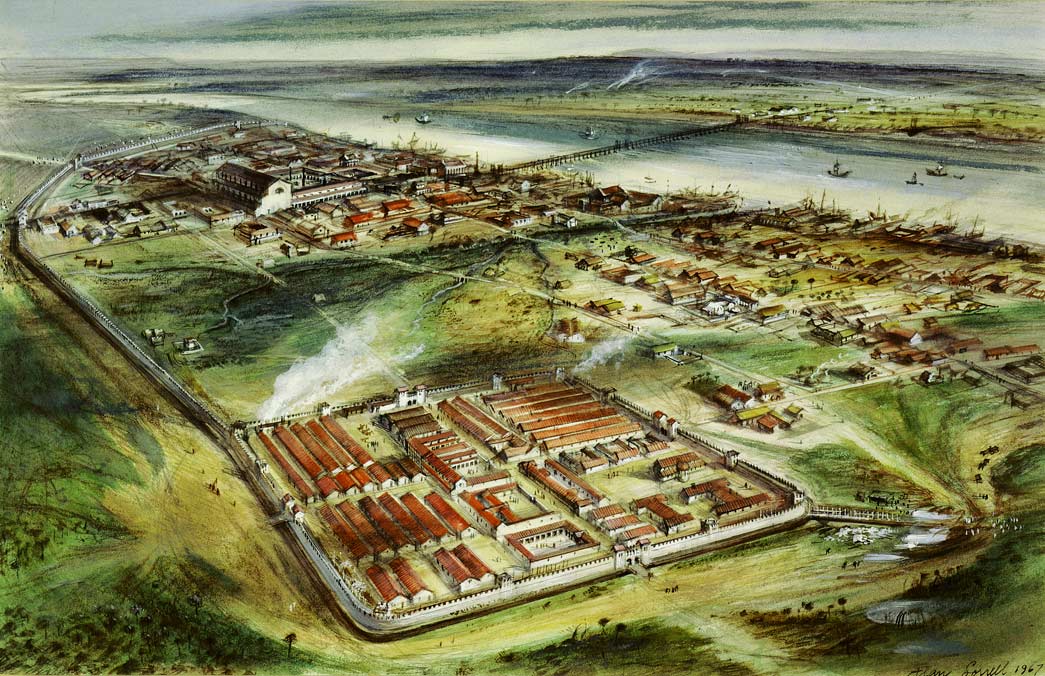

I have been working on a large-scale project to better understand Roman Londoners through the tools they left behind, buried under our modern streets. The Museum of London holds one of the largest collections of Roman tools in Europe, representing a huge variety of activities. Of the 930 tools recorded so far, 678 of them were recovered from a small area of the City of London, between Cannon Street Station and Finsbury Circus. In the Roman period, this was the course of the Walbrook stream, a small flood-prone valley now buried beneath London’s streets. In a bid to raise their houses above the floodwaters, Roman Londoners collected rubbish from across the city, dumping it in the valley to create building platforms. In the process, hundreds of everyday objects were buried in the waterlogged soils, creating an exceptional archaeological record.

Roll out the barrel(maker's saw)

The author holds a croze saw

ID no. 13656

Archaeologists usually categorise tools as for ‘metalworking’ or ‘woodworking’, but the tools from London show that this does not accurately reflect the specialisations and professions in which Roman Londoners were employed. This croze is a special type of saw. It would have been used to cut a channel around the inside of a bucket or barrel, in which the base would sit. This tool indicates the presence of coopers in Roman London, and indicates a high level of professional specialisation. These professions would have been a key part of people’s self-identification. Recently, a writing tablet was found at the Bloomberg site in the Walbrook valley, addressed to Iunio cupario: ‘Junius the Cooper’.

The Roman green belt

Working the ground in London has a long history, from today’s hipster urban farmers, through allotments and window boxes, to the Roman farming and gardening tools found in the city. The Roman city was more open than the one we know today. Even when the walls were built around the city, they enclosed green spaces around the edge of the settlement. Wealthy Londoners may have had properties set in formal classical gardens, particularly in the Later Roman period, when the city became less of a commercial hub and took on more of an administrative function. The city would also have been home to people who owned or had stakes in farms in the surrounding area, and we cannot be sure whether these tools were used in the city, or if people came here to buy or have tools repaired.

Head of Roman iron stamp

ID no. 1617

Putting a stamp on history

This iron stamp has the letters MPBR inscribed in reverse

onto its striking surface. This has been read as an abbreviation for Metalla

Provinciae Britanniae: ‘the

mines of the province of Britannia’. It was perhaps used by officials to stamp

metal ingots passing through London on their way to the Continent. If so, it is

a reminder that life in Roman Britain was not as cosy as we are often taught.

Military conquest followed by the exploitation of mineral resources is a

familiar aspect of modern colonialism.

Official stamps were used to mark objects made by or for the state, army or navy, but there are other stamps in the Museum that show the initials of private Roman citizens who also controlled aspects of industry in London. Stamps were put on leather hides and barrels as they moved around the country. Craftsmen also sometimes stamped products with their names, and some of these marks survive on the tools from Roman London.

Form or function?

When we look at tools from the ancient world, they can seem extremely familiar - we feel a close connection to the people who would have used them. The Roman period in particular is seen as a time when practicality triumphed, making it easy to see the link between their functional, everyday possessions and the ones we use ourselves. Objects such as this pot decorated with smith’s tools, however, show that superstition and the supernatural were a key part of Roman industry and everyday life. It is decorated with a smith’s hammer, anvil and tongs, and was found at the bottom of a timber-lined well in Southwark. It may have been part of a ritual closure deposit, an offering linked to the smith god Vulcan.

This project has been a fantastic opportunity to work with major museum collections, including those from the Museum of London, British Museum and Oxford's Pitt Rivers Museum, as well as finds recently excavated by commercial archaeological units in London. By combining the well-preserved tools from the museum collections, with the well-provenanced, but often more corroded tools from recent excavations, we have the opportunity to get the most complete image yet of the working communities of Roman London. Research on these tools is ongoing, with an expected completion date in September 2017.

The Working the Walbrook display closed in March 2017.

Want to get updates about the city's buried past straight to your inbox? Sign up for our Archaeology newsletter to find out about upcoming exhibitions, events and articles.