The Museum of London is planning a move to West Smithfield, into the magnificent Victorian market buildings. Smithfield has been a central point in the city for many centuries- three of our curators talk us through the rich history of Smithfield, future home of the Museum of London.

From monks to meat markets: the religious history of Smithfield

Roy Stephenson, London's Historic Environment Lead

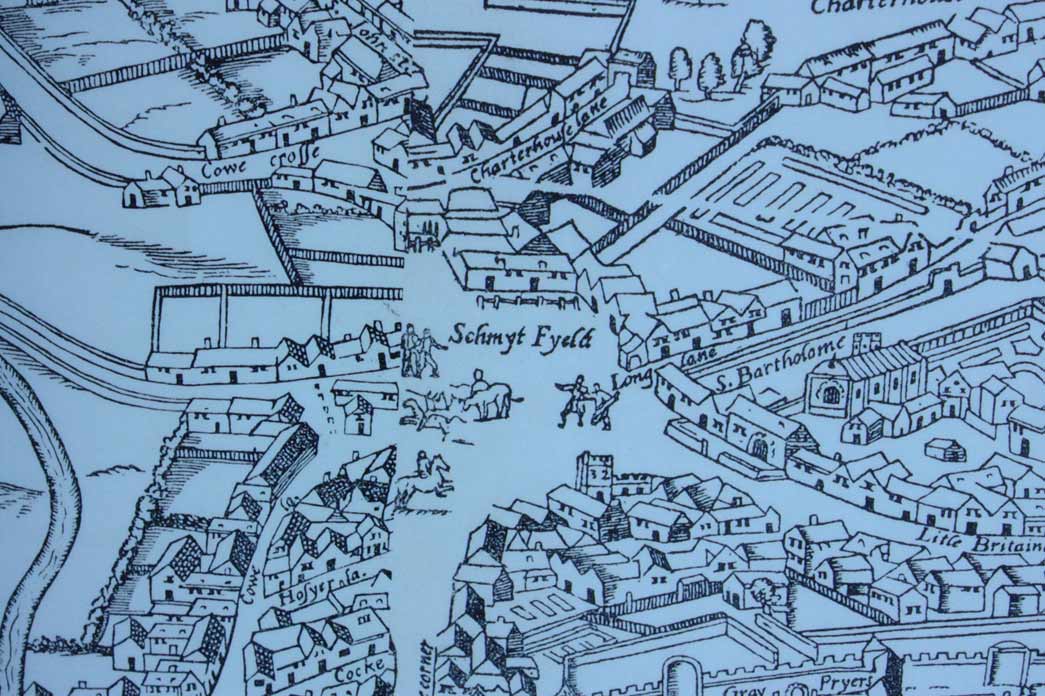

Smithfield has been an important site in London for over 1000 years: just outside the city walls, with a convenient grassy field and access to the River Fleet, it became the site of London's livestock markets.

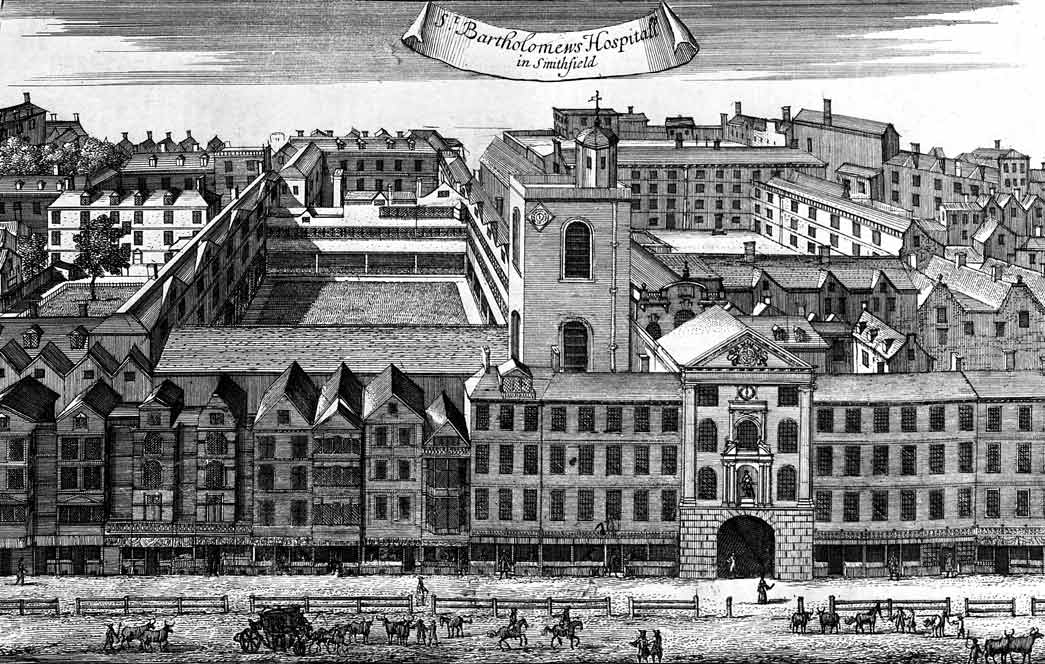

For many centuries, Smithfield or the ‘Smoothfield’, would have has a distinctive perimeter of religious houses. Immediately to the north was the Augustinian nunnery St Mary Clerkenwell, founded in 1144. To the south, the Augustinian St Bartholomew’s Priory and Hospital, founded in 1123 by the cleric Rahere, in thanks for his recovery from illness on a pilgrimage to Rome. The modern Bart’s hospital, as we know it today, can trace its lineage to this point, and Smithfield could be regarded as the origin of the hospital system in Britain- all the way to the 70th anniversary of the NHS in 2018.

Charterhouse, 1880

Built as a Tudor manor house on the site of the Carthusian priory

Beyond St Mary Clerkenwell was St John Clerkenwell, the priory of the Monastic Order of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem. Later in the 14th Century to the east was Charterhouse, a Carthusian Priory where the inmates lived solitary lives in separate cells.

Perhaps we can imagine standing in Smithfield at this time, in the late 1300s: the wide "Smooth Field" is almost surrounded by the substantial perimeter boundaries of these houses; to the south a way to Newgate, one of the great gates of the City of London; to the west the river Fleet and beyond, on the far bank, the Palace of Bishop of Ely.

This landscape of religious houses was dissolved at the reformation, between 1530 and 1570. But there are tangible monastic remains and influences, and they still dictate how the area feels to a certain degree.

Although modified and changed over the years the most substantial are the remains of Charterhouse, used as a Tudor mansion, a school and an alms house, and still the home to 40 brothers. The influence of Barts is huge: the church remains, and there is suggestion of the cloister, but the hospital grew to became a major presence in Smithfield, and a watch word in the world of medicine.

St John Clerkenwell exists as the gatehouse to the precinct which is part of the museum of St John. The Order of Knights of St John lives on as the St John Ambulance Service. St Mary's Clerkenwell has left its name to a parish church. All of these monastic houses have left their mark on the streetscape of modern London.

All the fun of Bartholomew's Fair

Kate Sumnall, Curator

Cloth Fair in the 19th century

Named after the medieval market held on this site. This etching, from 1892, shows the street before a new wing of St Bartholomew's Hospital was built on the site. ID no. 34.257/151

The date for our summer Smithfield 150 celebration was inspired by the traditional Bartholomew Fair, one of London's most ancient summer fairs- the first one was held in 1133!

When the monk Rahere founded St Bartholomew’s Priory in 1123, he also received a Royal charter to hold an annual cloth fair. The dues levied on the fair were an important source of revenue for the Priory. The fair lasted three days and was centred on St Bartholomew’s feast day, 24 August. It was held within the grounds of the priory, where the modern road Cloth Fair is situated today. This cloth fair became one of the largest and most important in the country. Merchants from all over the country and Europe visited to buy and sell cloth. During the late medieval period a large portion of England's wealth was linked with the cloth trade.

These earliest cloth fairs were focused primarily on the trade in fabrics, but there were also refreshments and entertainment. Famously, Prior Rahere was a court jester to Henry I before he founded the priory. During the cloth fair Prior Rahere would amuse the crowds with his juggling skills.

The fair changed dramatically in the 16th century as trade became easier with improved transport routes and the cloth merchants expanded their business beyond the fairs. The focus of Bartholomew Fair shifted away from cloth and more onto entertainment. An account of the fair written in 1598 describes the opening ceremony, wrestling and also the practice of releasing live rabbits amongst the crowds that children would chase.

Bartholomew Fair is one of the most famous and well-documented fairs. Ben Jonson wrote his comic play ‘Bartholomew Fayre’ in 1614. In this play Jonson presents a rare insight into everyday 17th century London life.

‘Now the fair’s a filling!

Oh, for a tune to startle

The birds o’ the booths here billing

Yearly with old Saint Bartle’.

Alongside the entertainment of the fair there was an undercurrent of trouble, violence and crime. Pickpockets were attracted by the crowds and distractions. In 1698 a Frenchman, Monsieur Sorbiére wrote,

‘I was at Bartholomew Fair… Knavery is here in perfection, dextrous cutpurses and pickpockets.’

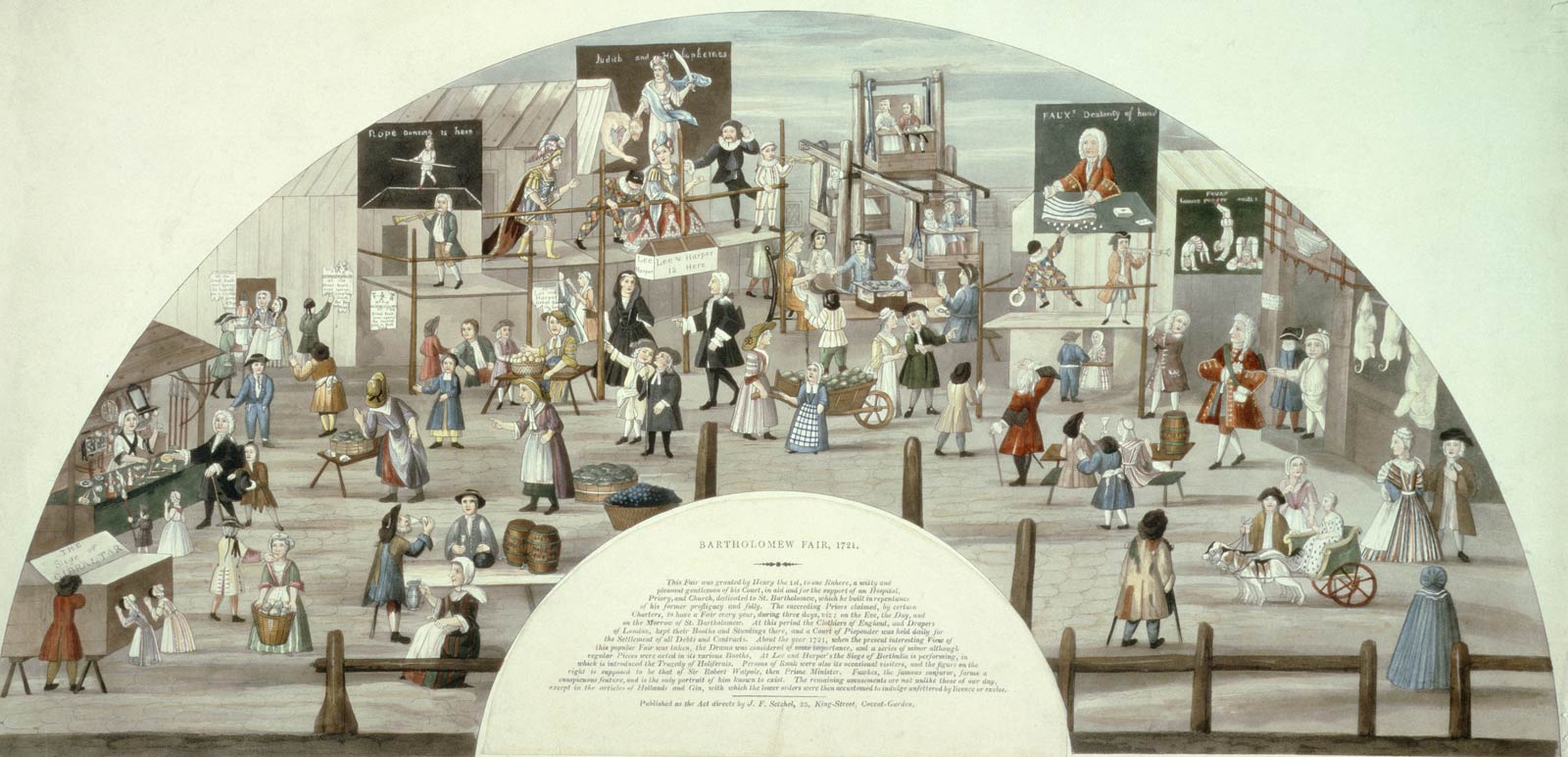

This lively watercolour of Bartholomew Fair shows the entertainments literally in full swing with the rides and sideshows displayed on the left.

The fair also had its own pie-poudre court, a temporary jurisdiction which quickly dealt with disputes, mainly ones concerning trade for example, in 1566 a man was sent to prison for using an unlawful yard-stick to measure cloth.

By the late 1600s, the fair had grown in popularity and size so it now spanned four parishes and lasted for two weeks. Entertainments included puppet shows, wrestlers, fire-eaters, dwarfs, dancing bears, performing monkeys, caged tigers, contortionists, tight rope walkers and astrologers. Also miraculous medicines, food and drink, tobacco, toys, ginger bread, mouse traps, puppies, purses, singing birds, Bartholomew Babies – ginger bread dolls, Bartholomew pigs – pigs roasted whole were all for sale.

In 1815 Wordsworth visited the fair and saw ‘albinos, Red Indians, ventriloquists, waxworks and a learned pig which blindfolded could tell the time to the minutes and pick out any specified card in a pack’.

The fair drew acts and crowds from all over the country and further afield. It was hedonistic and out of control. It was perceived to be a threat to polite society and there were various attempts at regulation. Finally after more than 700 years it was banned in 1855 for being “a great public nuisance, with its scenes of riot and obstruction in the very heart of the city”.

The end of the Bartholomew Fair also ties in with a period of great change in West Smithfield. At this time the livestock market was closed down and the slums were being cleared. It was the age of industrialisation; the railways were being built and the innovative market buildings were going to revolutionise the market. The new modern era was here.

Feeding the City: the Smithfield Meat Market

Alex Werner, Lead Curator, New Museum

Unloading meat and poultry at Smithfield Market, 1965

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

In terms of the grand projects of Victorian London, the London Central Markets at Smithfield have never really received sufficient acclaim. As we celebrate Smithfield 150, it is timely that we consider their unique and special character.

Surveying the buildings, their scale and ambition is certainly impressive. Sir Horace Jones, the City’s architect, was the mastermind of the project. He aimed to create ‘state of the art’ wholesale markets where salesmen, buyers and porters would be able to carry out their business efficiently, with well-designed stalls for displaying and storing meat and other produce. The roof structure, with glass louvres and slatted dormers, and the lay-out of the market were both important: they contributed to a good circulation of air, keeping the interior cooler than the outside temperature.

The buildings were a reflection of the modernity of Victorian city. Like many market buildings of the second half the nineteenth century, they owed a debt to Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace in their creative use of glass, timber and iron.

One aspect of the London Central Markets was particularly revolutionary, though largely hidden. All the buildings were constructed over railway goods yards. For the first time ever, meat was delivered by underground railway direct to a large wholesale market in the centre of a city.

This came about because, in 1863, the eastern terminus of the world’s first underground railway, the Metropolitan Railway, had opened at Farringdon. Over the next five years, the Smithfield area was ringed and dissected by underground railway lines and tunnels. The Metropolitan had extended eastwards to Moorgate by July 1866 and to the south had joined up with the London, Chatham and Dover Railway station at Ludgate Hill. This enabled the wholesale market to connect seamlessly with the capital’s railway system, especially the part which ran under the metropolis. From the Metropolitan Railway that ran beneath the market, there were junctions with the Great Western, Great Northern, Midland and London, Chatham and Dover Railway. The Times, on 18 August 1868, described this as ‘ a wonderful piece of engineering skill and adds another to the long list of engineering works which places London ahead of any other city in the world’. In the basement, a number of hydraulic lifts alongside the sidings raised the meat that arrived on railway waggons up to the market floor above.

Standing today in the Grand Avenue of the London Central Markets, it is worth remembering that under one’s feet there is an elaborate system of brick arches, wrought iron girders and cast iron columns supporting the roadway and the buildings on either side. 150 years ago the first of the great markets buildings at Smithfield opened, linking up with the underground railways of the capital. And in a few months’ time, the Elizabeth Line will carry its first passengers to Farringdon Station. This immense underground achievement of the 21st century rivals that of our Victorian forebears who laid out and created the wholesale meat markets at Smithfield and the world’s first underground railway.