The Great Fire of London is a very well-known disaster, and has been researched and written about extensively ever since 1666. However, there are still some enduring myths and misconceptions that the Museum of London’s Fire! Fire! exhibition (May 2016 - April 2017) aimed to tackle.

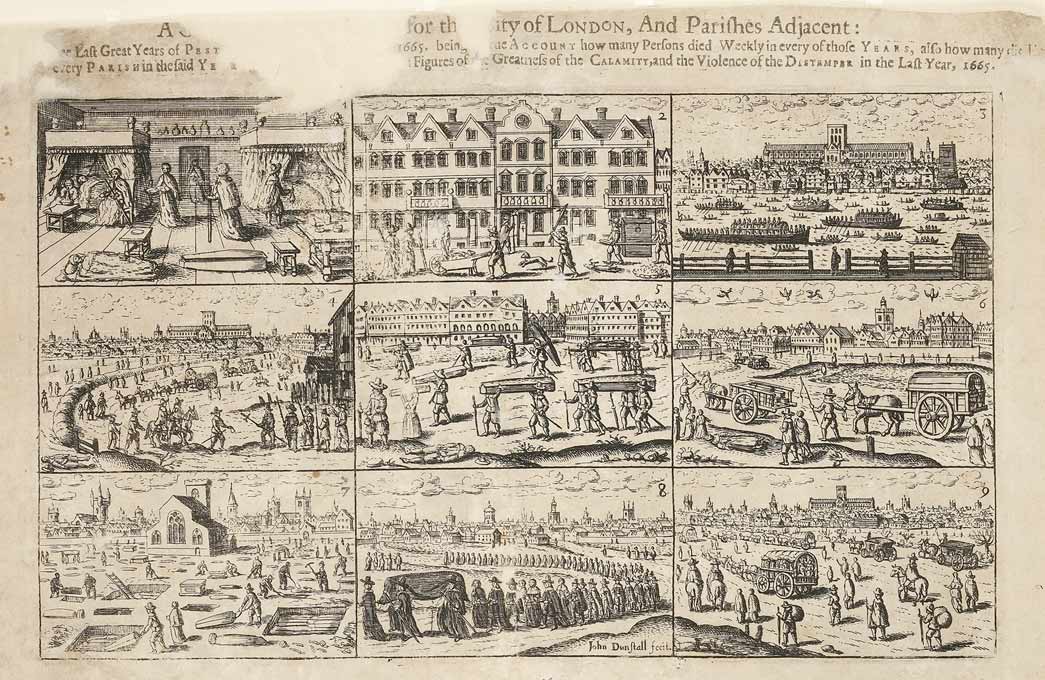

Myth #1: The Great Fire stopped the Great Plague

Map of London in 1666

The fire left many areas that had been devastated by the plague untouched.

This is the myth that I hear people talking about most often. They may have read it in a children’s book or heard it at school. The idea is that there was a silver lining to the tragedy of the fire, as it ended the great plague that swept the city from 1665-66. This was the last major outbreak of the bubonic plague in London, and killed 100,000 Londoners- about 20% of the city's population. The fire is supposed to have wiped out London’s rats and fleas that spread the plague and burned down the insanitary houses which were a breeding ground for the disease. If anyone asks you about this, you can tell them that it’s not true. Here’s why:

- The Great Fire only burnt about a quarter of the urban metropolis so it could not have purged the plague from the whole city.

- Though the outside walls of houses rebuilt after the fire had to be built from brick, there were no major improvements to hygiene and sanitation afterwards.

- Many of the areas that were worst affected by the plague, such as Whitechapel, Clerkenwell and Southwark, were not destroyed by the fire.

- The numbers of people dying from plague were already in decline from the winter of 1665 onwards.

- People continued to die from plague in London after the Great Fire was over.

This myth seems to have grown up because the two catastrophes were so close together and because the Great Plague of 1665-66 was the last major outbreak of the disease in this country. We are still not sure why the plague did not return to our shores after it faded out in the 1670s but it wasn’t due to London’s 1666 fire.

Myth #2: The Great Fire spread due to the thatched roofs of London’s houses

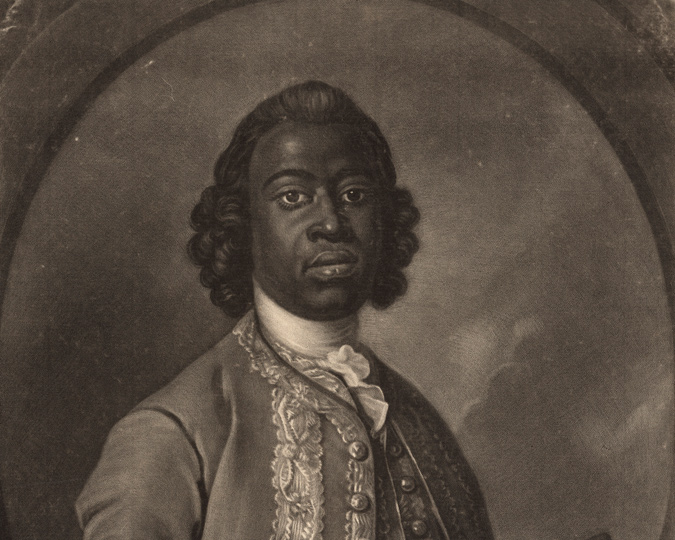

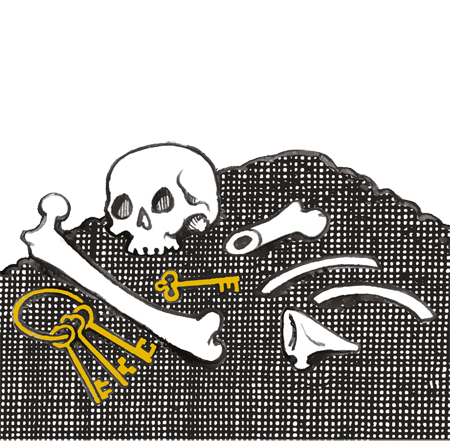

How many people died during the Great Fire?

We don’t know for sure. Amazingly, fewer than ten deaths were recorded. One of the people killed was 80-year-old watchmaker Paul Lowell. He refused to leave his house on Shoe Lane even though his son & friends begged him to go. His bones & keys were found in the ruins.

In fact, thatch had been banned within the City of London by building regulations dating back to 1189. These rules were reinforced after a terrible fire in 1212 when an estimated 3000 people died. Shortly after this fire, the City authorities ruled that all new houses had to be roofed with tiles, shingles or boards. Any existing roofs with thatch had to be plastered. The medieval regulations appear to have been successful in preventing large-scale fires. John Stow, in his 1598 Survey of London said ‘since which time [referring to introduction of the rules], thanks be given to God, there hath not happened the like often consuming fires in this city as afore.’

By 1666, the vast majority of houses in the City would have been tiled. Even if there were a small number of thatched buildings lurking in the densely-packed streets, they were not in significant numbers to be noted as a cause of the Great Fire by 17th-century authors. The London Gazette and Rege Sincera's Observations both Historical and Moral upon the Burning of London both mention timber buildings as a problem but not thatch. Sincera wrote about ' the weakness of the buildings, which were almost all of wood, which by age was grown as dry as a chip'. The London Gazette's reporting of the disaster says it began 'in a quarter of Town so close built with wooden pitched houses'.

Myth #3: London was rebuilt in brick & stone thanks to the Great Fire

Eight lives left...

Samuel Pepys saw a cat being pulled from the ruins of a burnt-out building by the Royal Exchange on 5 September. He wrote in his diary: ‘I also did see a poor cat taken out of a hole in the chimney…with the hair all burned off the body, and yet alive.’

While it is true that the February 1667 Rebuilding Act stated that ‘all the outsides of all Buildings in and about the said Citty be henceforth made of Bricke or Stone’ there were many brick buildings in London beforehand. In fact, records show that there were even brick houses on Pudding Lane, that notorious street where the fire began, before 1666.

Royal proclamations dating back over 60 years demanded that new buildings be built from brick. In March 1605 James I said that no one was to build a new house in London unless it was made from brick or stone because he wanted to reserve the country’s timber for the navy’s ships. Uptake was slow, however, and later proclamations repeated this demand several times, such as in October 1607, when King James stated that new brick or stone buildings would ‘both adorne and beautifie his said City, and be lesse subject to danger of fire'.

As these rules only applied to new houses, and appear to have only been sporadically obeyed, the Great Fire became the opportunity to enforce, re-state and refine existing rules. The disaster affected such a large area that thousands of brick houses had to be built to replace those that had been destroyed. This has left us with a false impression that the fire introduced brick to London.