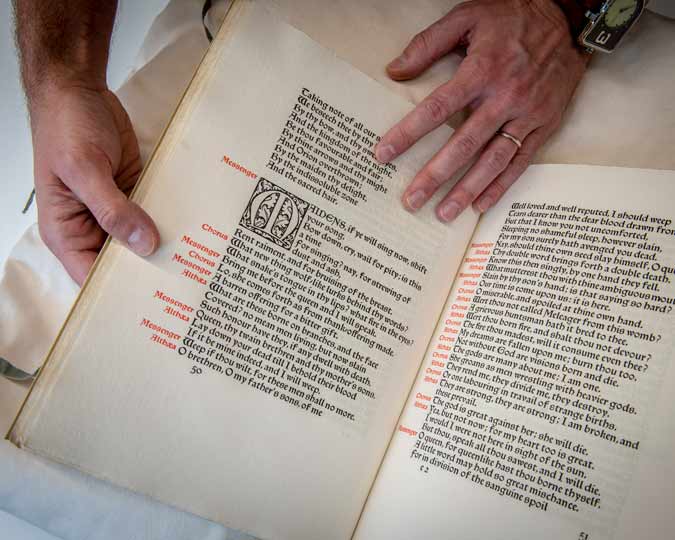

“You don’t need thumbscrews or knives to torture someone if you can perform the Cruciatus curse … that one was very popular once, too” J K Rowling, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

By ‘once’, the dark wizard Barty Crouch Jr (disguised as Professor Mad-Eye Moody) meant the First Wizarding War. But he might just as well have been talking about Roman London. We shall never know if Tretia Maria suffered the same as Harry did when Voldemort screamed the Latin ‘Crucio!’ – “pain beyond anything Harry had ever experienced; his very bones were on fire; his head was surely splitting” – but that was certainly the intention of the person who cursed that unfortunate woman from Londinium.

“I curse Tretia Maria and her life and mind and memory and liver and lungs mixed up together, and her words, thoughts and memory …”

Lead-alloy tablet cursing Tretia Maria, violently nailed up with seven nails.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Used under Creative Commons license

The curse was scratched on a thin sheet of lead alloy, and is one of eight such curses that are known so far from Roman London. All too often these angry and vicious little objects have been treated as mere ‘curiosities’ – much less useful than tombstones or writing tablets, for instance, in helping us understand how people lived in the past. However, if we study them carefully, we can see into strata of Roman society lying beneath those recorded by contemporary historians and can come very close to real people in a particular moment of time.

Take a curse tablet discovered in a drain in the Amphitheatre:

“I give to the goddess Deana my hat and scarf less one third. If anyone has done this, whether boy or girl, enslaved or free, I’m turning them in. And, through me, let them be unable to live.”

Invocation to the hunting-goddess Diana, demanding the death penalty for the thief of a hat and scarf.

Found in the Amphitheatre. Letters photographically enhanced. Image © Andy Chopping, MOLA

Here we have someone whose clothes have been stolen, and who is asking a goddess to help track down the thief and punish them. We shall never know why these particular items should stir such anger that the victim would demand the death penalty. Gifts from a lover, perhaps, or treasured family heirlooms? Be that as it may, the curse was almost certainly the last desperate throw by the victim of a system that made it very difficult for an ordinary person to track down a thief and bring them to court.

Under Roman law, it was up to the victim to bring a private prosecution. And even if successful, there was no guarantee they would recover the stolen goods. The court would require the thief to pay a fine equivalent to the value of the property, but would not be responsible for reclaiming the property itself. Everything favoured the rich and influential, who could send out servants to hunt down thieves and beat them up if they didn’t comply with court orders.

Our London victim presumably had no influential earthly patron, and so the best they could do was to beg for Diana’s help. The curious pledge of two-thirds of the stolen goods is itself probably rooted in Roman law. A court would sometimes issue a warrant permitting a search of a suspect’s house. If stolen goods were found, the fine would be tripled. A goddess would have the power to search the house of any mortal, so not surprisingly, our victim was only too happy for her to take the premium that will result from a successful investigation.

Were the hat and scarf nicked from a seat in the amphitheatre while the owner was in the loo? That’s the natural assumption but it’s not necessarily correct. If one was going to get supernatural assistance, it made sense to call upon a deity with particular expertise in dealing with criminals, and to do so in a place where they were known to reside. Diana, goddess of hunting, would be a good choice. In the guise of Nemesis – Retribution – she frequented amphitheatres and saw to it that many miscreants were put to death there.

Other powerful gods lived in water, and so it’s no surprise that lead curses are often found in rivers or springs (as at Bath). If the person who had wronged you were a sailor or merchant, Neptune would make short work of them if you could get the sea-god on your side. One such curse tablet has been found in the Thames. On one side we read:

“I ask you Metunus that you avenge me on that name. That you avenge me before nine days come. I’m asking you Metunus that you avenge me before nine days come.”

Invocation to the sea-god Neptune, demanding justice for an unspecified crime.

The names of the accused are listed backwards and in a circle – effects that would maximise the magical impact of the spell.

This plea to the supernatural was almost certainly made by someone of British ancestry, who was fluent enough in speaking Latin but not formally schooled in writing it. The sounds of ‘M’ and ‘N’ are easily confused and a Celtic speaker would struggle in particular with ‘PT’, a combination of consonants that was not used in their language. Hence ‘Metunus’, rather than ‘Neptunus’. This document, moreover, brings us close to witnessing the very act of casting a spell, reminding us that it was not just written but muttered, chanted or simply shouted out. In the repetitions – ‘VENDICAS’ (‘avenge’) appears three times – we clearly hear the voice of ritual incantation.

There was no need to record either the name of the petitioner-cum-magician nor the nature of the offence. The god was all-seeing and already knew. But the name of the offender was essential. Not because Metunus was ignorant of it, but because a name was a powerful surrogate for its bearer. Handing the god a name was tantamount to turning in that person.

On the other side of the tablet, we find ‘that name’ is in fact many names:

“Exsuperantius, Silviola, Sattavilla, Exsuperatus son of Silvicola, Avitus, Melussus … you’re handed in, I’ve beaten you … Santinus, Mag…etus, Antonius, Santus, Vassianus, Varasius”

The words are written backwards, starting in an anti-clockwise direction around the four sides of the document and then filling in the middle. Backwards writing presumably made the spell more effective, demonstrating the curser’s competence in the dark arts. The circular arrangement perhaps mirrored the ritual in Romano-Celtic temples, where worshippers processed around a central image of the deity.

The accused may have been members of an extended family or of a business association – colluders in the theft of property or in dodgy commercial dealings – but their names suggest they were very ordinary people, typical of the tens of thousands who lived in Londinium during its 350-year history. There were many Sancti and Sanctini (‘Saints’), and quite a few exotically-sounding Exsuperati/Exsuperantii (‘Victors’) in Britain and France, though fewer in Mediterranean lands. One of Vassianus’s forebears was perhaps once enslaved. His name is derived from the Celtic for ‘servant’ (from which comes the modern word ‘vassal’).

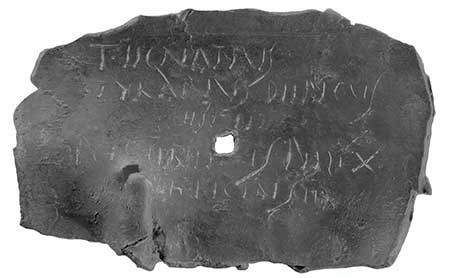

Curse scratched on lead alloy and nailed up.

Translation: ‘Titus Egnatius Tyrannus is cursed and Publius Cicereius Felix is cursed’. Both men were Roman citizens. The ‘wizard’ was perhaps their social inferior, using their full official names in a mock-deferential way.

This curse was consigned to the depths of the river, whereas others were nailed up on walls, publicly shaming the perpetrators of crimes. But driving a nail through the soft lead of a tablet was not done for practical reasons alone. It was to wound the accursed – care often being taken to make the hole exactly where their name was written – just like pins driven into a Voodoo doll. This was a concept the Romans understood well. So well in fact that the word ‘to fix or fasten down’ (‘defigere’) came to be the usual word for ‘to curse’. Here, in a literary context, we see the Latin poet Ovid tormented by one of his many lovers:

“Has some treacherous sorceress cursed/fixed my names (‘defixit nomina’) in wax,

And driven slender needles through the middle of my liver?”

Such was the power of the dark arts that bewitched the unlucky Tretia Maria. Her little tablet, moreover, was pierced by not one but by seven nails. As we look at it, we can sense the fury with which they were hammered through. We should recoil in horror at the thought.