We reveal a set of pioneering daguerreotypes of Queen Victoria, previously unseen by the public. This cutting-edge Victorian technology shows the Queen as you've never seen her before.

These images may seem somewhat faded and old-fashioned today, but in the 1850s they were the absolute pinnacle of photographic technology. They are stereoscopic daguerreotypes, two very similar pictures which when seen side-by-side through a special viewing device, create a three-dimensional image of their subject: in this case, Queen Victoria. Photographed about 1854, when Victoria was just 35, these images show a younger, elegantly dressed queen: quite different from the traditional public conception of an older Victoria, still dressed in black mourning clothes after the death of her husband Prince Albert. Victoria and Albert were the early adopters of their day, popularising the new technology in Britain.

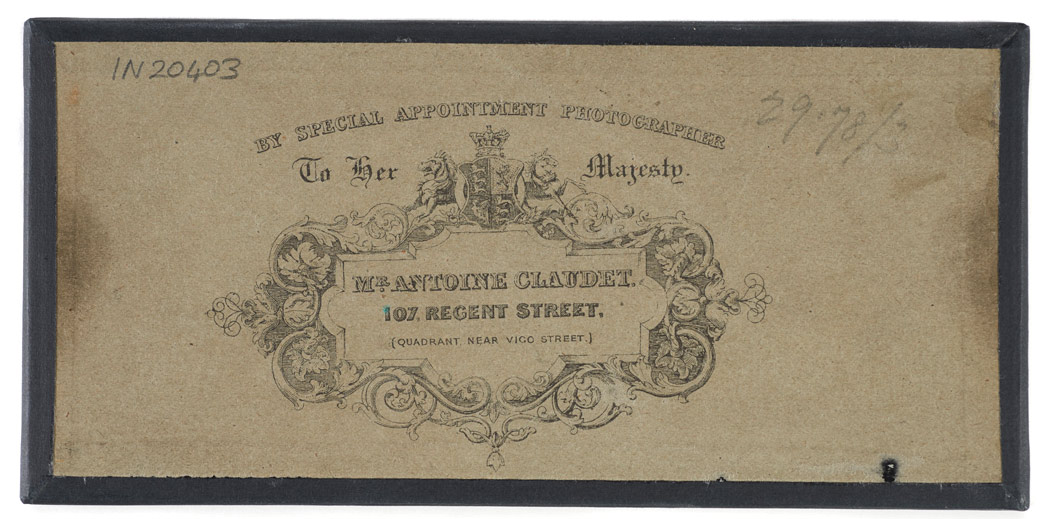

In 1851, a French photographer came to London's Great Exhibition to show off his skills. Antoine Francois Jean Claudet was one of the pioneers of early photography, learning his trade from Louis Daguerre, inventor of the first commercially successful type of photograph: the daguerreotype. This complex process etched an image onto a silver-plated copper slide, creating an extraordinarily sharp and accurate image.

Daguerreotypes have been called "mirrors with memory", as they retain their silvery finish and shift appearance depending on lighting and viewing angle. They are also extremely fragile: the delicate pattern of tarnish depicting the image can be damaged by a light touch. These daguerreotypes are sealed in a protective glass case.

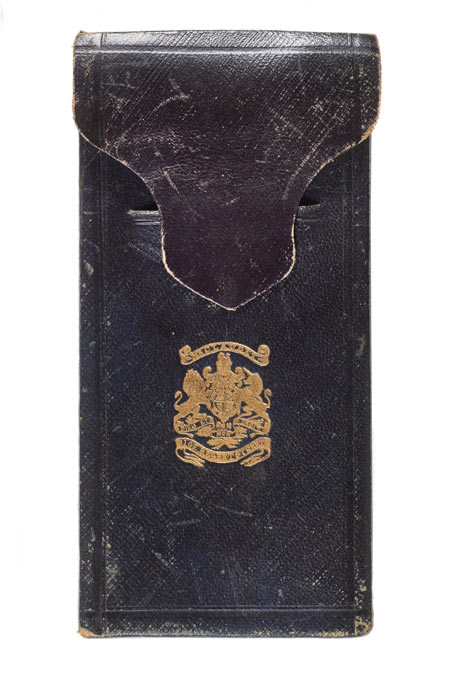

Leather carrying case, 1850

Bookshaped, expanding case of dark blue leather. Decorated with gilt. Brass clasp. Opens to reveal two daguerreotypes and pair of binoculars

Senior Curator of Paintings, Prints and Drawings Francis Marshall explains that it was royal patronage that kick-started Claudet's career: "Claudet’s work won the highest award for portraiture at the Great Exhibition. His new, stereoscopic views also attracted the interest of the Queen and Prince Albert, They were probably the first people in Britain to buy one of the special, twin-lensed devices, on which to view them.

"Thanks to Victoria and Albert’s patronage and the success of photographic exhibits at the Great Exhibition, sales of stereoscopic photographs became extremely popular. Claudet was able to open the grandly-titled Temple of Photography, creating and selling daguerreotypes and viewers, at 107 Regent Street.

"In 1853 Claudet was invited to take various portraits of the royal family, and was appointed a Royal-Photographer-in-Ordinary – the photographic equivalent of the Queen’s court painter, Franz Xaver Winterhalter. That same year the Queen and Prince Albert were also invited to become patrons of the Photographic Society of London."

These daguerreotypes were probably intended for private use by the royal family. Victoria and Albert readily adopted photography, sitting for daguerreotypes for the first time in the early 1840s and commissioning photographic portraits of their children from 1848. In fact, Victoria and Albert both learned how to create their own photographic prints, although there are no known surviving images made by the royal couple.

It's difficult to view these images as they were meant to be seen- through the binocular viewfinder in the leather case. Stereoscopic views create a three-dimensional effect, by showing a slightly different image to each eye, but they normally need the help of a stereoscope to do so. Still, you may be able to create the effect with these images. Try unfocusing your eyes and varying how close you hold your head to the screen. What you want is for the left image to be seen only by your left eye, and the right image by your right eye. You might just see Queen Victoria jump out at you!