It’s common knowledge that the Romans brought wine-drinking culture to Britain. But who would have guessed that the first attempt to make British wine dates as far back as the 1st century CE? Sherds of wine jars found close to present-day London point to that surprising conclusion. The wine produced might not have been commercially successful, but full marks for effort. Read on to know more.

On present evidence, there can be little doubt that it was the Romans who introduced winemaking to Britain. While it is true that seeds of the cultivated grape, Vitis vinifera, have occasionally been found in prehistoric contexts, and that people of high status in the Iron Age would sometimes drink wine imported from Europe, there is nothing to suggest that the techniques of growing and turning grapes into wine were practised in Britain before the Roman invasion of 43 CE.

Stone sculpture from France, probably part of a wine merchant’s tombstone, showing barrels on a river boat. On the shelf above are Gauloise amphorae. (Courtesy: WikimediaCommons)

British vineyards

Wineries are difficult to identify archaeologically, but a Roman vineyard in Northamptonshire covering 11 hectares (around 20 football pitches) is now well known. Less than a tenth the size of the largest of modern English vineyards — though roughly the same size as international-award winning Langham’s vineyard in Dorset, for example, which produces around 60,000 bottles per year — it must have been substantial by the standards of Roman Britain. Dating to the second, possibly into the third centuries, it is unlikely to have been unique. In his efforts to restore north European agriculture after devastation by war, Emperor Probus from 276 to 282 CE, singled out the “Brittanni”, along with the Gauls and Spaniards, as people to be encouraged to keep vines and make wine.

Long before this, however, there had been attempts at commercial wine-making just a few miles north of Londinium. The evidence, which is little known, comes not from excavation of a vineyard but from the discovery of sherds from distinctive wine jars — amphorae — in the stores of the Museum of London. They date from the 1st century CE, perhaps as little as 20 or 30 years after the Roman conquest.

The secrets of the amphorae

One group of sherds, the remains of 25–30 smashed vessels, derive from a type of amphora about 1m tall, with a capacity of 20–25 litres. It had a long neck, a pair of long elongated handles and a pointed base. The most important type of wine amphora in the western Roman Empire during the 1st century is commonly labelled “Dressel 2-4” — as a tribute to German archaeologist Heinrich Dressel, who first classified it. The amphora dump was unearthed in 1975 in the grounds of the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital on Brockley Hill, immediately north of Edgware, on the west side of the A5. The excavator, Stephen Castle, plausibly suggested that it was debris from a traffic accident on what’s now Watling Street, the Roman highway whose course the modern road follows.

![Neck and handle (right) of a large ceramic container (amphora), like the one on the left (© The Trustees of the British Museum). These large vessels were used to transport wine from the Mediterranean. The right amphora sherd, unusually, was made near London and suggests that wine was produced in the area. (ID no: BH37[BH75 HE/1])](/application/files/1816/4502/2239/02_British_vintage_wine_1045_Dressel_2-4_amphora_roman_era_london_wine_MoL.jpg)

Neck and handle (right) of a large ceramic container (amphora), like the one on the left (©The Trustees of the British Museum). The vessels were used to transport wine from the Mediterranean. The right amphora sherd, unusually, was made near London and suggests that wine was produced in the area. (ID no: BH37[BH75 HE/1])

![A Sulloniacae Gauloise type amphora, made in Brockley Hill. (ID no.: GDV96[304]<P30>)](/application/files/4516/4502/2368/03_British_vintage_wine_450_Sulloniacae_Gauloise_type_amphora_MoL.jpg)

A Sulloniacae Gauloise type amphora, made in Brockley Hill. (ID no.: GDV96[304]<P30>)

Made near Londinium?

But while almost every other Dressel 2-4 amphora found in Britain would have been imported from Europe, expert analysis of the clay fabric showed that these sherds were made locally! The entire district, in fact — which the Romans probably knew as Sulloniacae — was a major centre for pottery manufacture in the 1st and 2nd centuries. Nor were these the only amphorae made there.

The Museum of London’s stores contain many fragments, and a couple of complete examples, of an entirely different type of wine jar. The largest examples stand little more than 0.5m high, with a flat base and short neck. However, being both thinner-walled and larger in diameter, their capacity was greater than that of the Dressel 2-4: up to 30 litres at least. This type of amphora is often labelled “Gauloise”, reflecting its ubiquity in France. But, again, expert analysis has revealed that these particular examples were made locally at Brockley Hill.

Could it be that these amphorae merely attest to the bottling of wine imported from abroad? Do they necessarily indicate local cultivation and wine-making? Evidence from the main wine-producing regions of the Roman Empire — Italy, France or Spain, for example — points to amphorae being made for the purpose of transporting commodities, not for decanting them from larger containers, such as barrels. In the case of olive oil, as well as wine, the amphorae that would transport that commodity were usually made on or close to the estate where it was produced — not by specialised potters in central locations. Because of their weight and size, it made no commercial sense to transport empty amphorae many miles from kiln to press, especially if the journey had to be made by road.

![A French (Gauloise) type wine jar, but made in London. “Senecio” was probably the owner of the vineyard, rather than the potter. His name is of a standard Roman type, but he may well have been a Briton. (Courtesy: University of Southampton (2014) Roman Amphorae: a digital resource [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor] https://doi.org/10.5284/1028192)](/application/files/7016/4502/2500/04_British_vintage_wine_1045_Sulloniacae_pottery_ADS-MoL.jpg)

A French Gauloise type wine jar, but made in London. “Senecio” was probably the owner of the vineyard, rather than the potter. His is a standard Roman name, but he may well have been a Briton. (Courtesy: University of Southampton (2014) Roman Amphorae. York: Archaeology Data Service https://doi.org/10.5284/1028192)

Different wine-making traditions?

A particularly intriguing aspect of the discovery of these two types of amphorae, is that they point to two different wine-making regions and, quite possibly, to two entirely different wine-making traditions! Gauloise amphorae were made almost exclusively along the Mediterranean coast of France and in the Rhône valley, whereas Dressel 2-4s were made in many different locations. Especially associated with Italy — where they were used to bottle vintages such as Falernian, arguably the most famous and highly regarded wine of antiquity — they also carried many wines from southern and eastern Spain. It is tempting to conclude that there were two very different viticulturists at work, perhaps not concurrently, at Sulloniacae, during the 1st century CE: one from France, and the other from Italy or Spain.

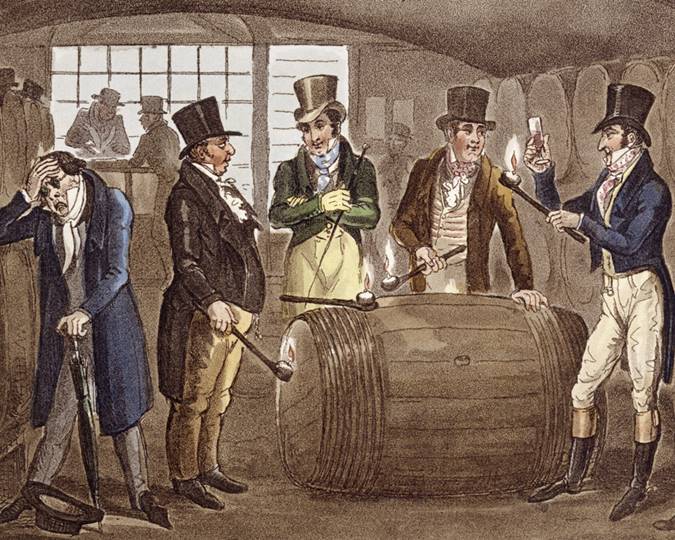

Part of a wall painting from Rome showing followers of the wine-god Bacchus drinking and dancing in a garden. (©TheTrustees of the British Museum)

A uniquely British approach

This would be consistent with what we know of the Brockley Hill pottery industry as a whole. The widely spread workshops and kilns, apparently concentrated to the north of Edgware but with outliers in St Albans and on the northern outskirts of Londinium itself, worked in a fully Roman style. Their ceramics satisfied the needs of a burgeoning immigrant population in the capital, along with aspiring Britons, who were cooking in an essentially Mediterranean style. Their two most distinctive products were “flagons” — used to serve the wine now in demand at dinner parties — and the mixing bowls, “mortaria”, that were required by cooks to prepare the sauces and marinades that were an essential part of Roman cuisine. Stamped trademarks indicate that the utensils were made by immigrant potters working alongside local British craftworkers. The attempt to produce local wine, by involving experienced practitioners from other provinces is, therefore, entirely consistent with the ambitions of this important London industry.

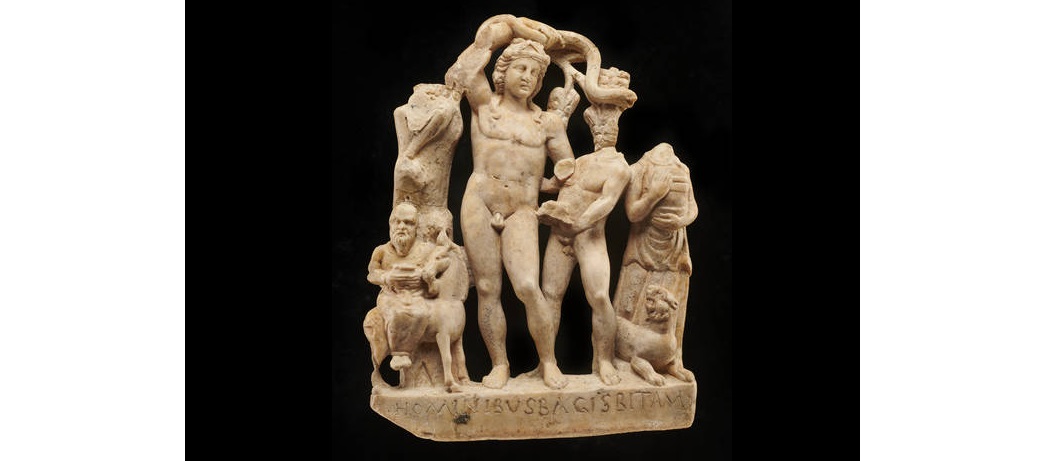

A marble sculpture from the Temple of Mithras in London depicting Bacchus and his followers. Bacchus was the Roman god of wine. Above his head is a vine branch. (ID no.: 18496)

A commercial success?

Apart from the type of vine, the most important element in viticulture is location. Brockley Hill lies on a steep southward-facing slope and so has exactly the right aspect. On the other hand, the subsoil is sand, silt and clay (the Claygate Beds) capped by gravel. Wine buffs hotly debate the significance of terroir in the success of a vineyard, but it is surely significant that many of England’s most successful vineyards today are on chalk. Vineyards such as Ridgeview (Sussex), which has a clay-with-limestone subsoil, are the exception rather than the rule.

Marble relief showing transport of amphorae, from 2nd century CE. (Courtesy: Fletcher Fund,1925/The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Equally difficult to assess is the significance of average temperatures in historic Britain. A colder or warmer climate may or may not have been helpful, depending on whether there was a concomitant impact on rainfall — not to mention the precise location of the vineyard with respect to frost hollows.

Yet, whatever the influence of these unquantifiable competing factors, it is unlikely that a connoisseur from Italy or France would have been satisfied with any wine produced in Britain. The greatest vintages of the ancient world were sweet white wines, which can be made only from grapes that have ripened to a degree impossible even today in Britain — despite global warming. Among the most successful wines made here at the present time are dry sparkling wines. These, as in the similar climate of northern France (Champagne), are made from grapes that are not over-ripened but have high acidity. So, with the ancient consumer’s palate — attuned as it was — when the demand for authentically Mediterranean culture was at its apogee in the 1st century CE, Vinum Sulloniacis was doomed to commercial failure, as indeed is indicated by the fact that its amphorae are seldom found outside the production sites themselves. The first British wine was an experiment that barely lasted a couple of decades!