As part of our Listening to London project, volunteer researchers share a selection of recordings from our oral history collection, shining a light on their collective memories of London’s docks, port and river.

London would not be the city it is today without its port. Once the busiest in the world — and now the biggest in Britain — the Port of London handles over 45 million tonnes of goods a year. The Museum of London has worked to capture the personal stories of the people who have kept the port going over time — from dockers to typists, crane drivers to river pilots, and even makers of pie and mash. The first oral history interviews the museum ever recorded were with people working in jobs related to the port and river in the 1980s.

Our oral history collection brings to life this rich social history, with recordings of people who worked in the port and riverside industries in their own words through the oral history interviews. The selection these recordings from the museum’s collection was led a group of volunteer researchers with unique personal connection to these stories. Together, they listened to more than 100 hours of interviews, choosing the final recordings for display.

Here, they share more about the interviews from the collection that connect to their own stories.

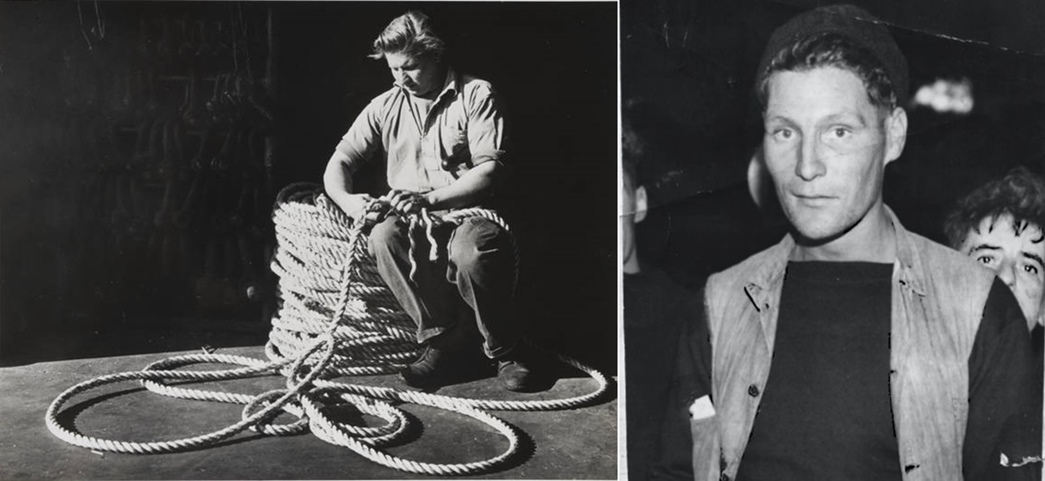

Rigging heritage: Joan Gandy

The docks and the East End of London are part of my heritage — volunteering on this project was a chance to reconnect with my family history. Many of my relatives worked in those trades which kept the docks functioning, including my dad, Tom Webster who was a ship’s rigger with a ship repair company. I wanted to share this interview with tackle man Charles Carpenter, on the art of splicing rope. Carpenter is a master of his craft, enthusiastic about sharing his knowledge. Listening to this reminded me of my dad’s work with ropes.

My dad took great pride in his work and was highly skilled. One of his proudest moments was helping to restore a rigged steamship — The RSS Discover — that was used for Antarctic expeditions. He would come home smelling of rope and oil, a very evocative smell for me.

He brought his skills home too. While other people had a nylon washing line tied in a knot at the end, ours had a beautifully spliced handle. One Christmas our son got a toy pirate ship as a present — I’m sure it was the only one fully rigged with rigging thread. My dad spent ages working on it that Christmas Eve.

First impressions: Gemma Suyat

I was intrigued to learn about first impressions of the docks through the voice of Eileen Gibbons. Eileen, who was interviewed by the museum in 1989, worked on a mobile canteen on the Royal Victoria Dock — very close to where I live. I’ve always found it to be calming and scenic, right by the water and away from the chaos of East London.

It was fascinating to compare our first impressions. For Eileen, the docks was a scary place — the fog created a feeling of unknowing and fear, and the deep water appeared intimidating; a contrast to my experience today. Now, when I walk along Royal Victoria Dock, I can’t help but think of its past life as a base for the cargo industry, and how much it has transformed since. One thing that remains is the strong presence of the water and how significant it is in shaping one’s perception of the docks.

Remembering grandad: Deborah Levett

I was amazed to come across a recording of my own grandad, George Pye, in the museum’s collection. It turns out he was one of the people to be interviewed in the 1980s. All three Georges in our family — my dad, grandad and great grandad — were stevedores in the Millwall and West India Docks. It was lovely to hear my grandad's voice and feel he was in the room again. I'd recognise that voice anywhere. I have listened to his interview in detail and found this section particularly interesting, as he describes the type of cargo he worked on over the years.

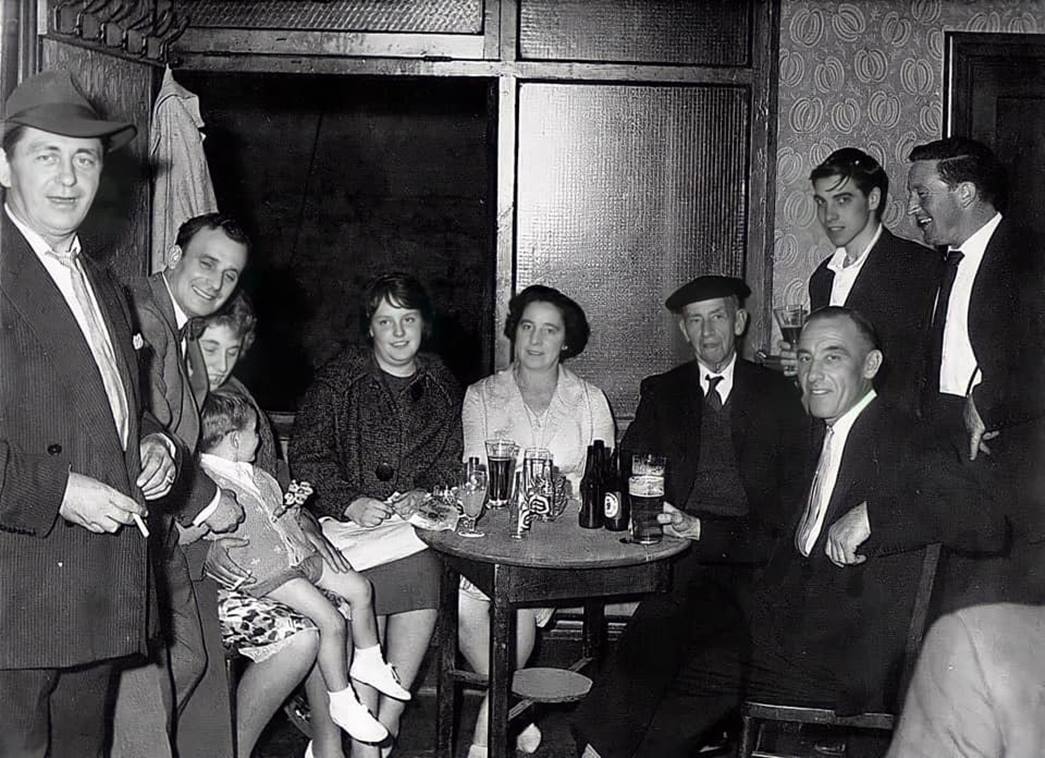

Pub crawls: Nick Corrigan

It is difficult to ignore the role of pubs in the history of the docks. Pubs were a place for business, union meetings, doing deals and getting jobs as well as meeting friends. One of the best known — Charlie Brown’s (originally the Railway Tavern pub in Limehouse) — was enjoyed by locals, dock workers and overseas seamen alike.

Rudolph Murray was a merchant seaman from Barbados who was interviewed by the museum in 2005, as part of a project to record experiences of people who worked for the British shipping line, the Harrison Line (T&J Harrison). Here he recalls his memories of visiting Charlie Brown’s.

As I listen to Rudolph’s account, I’m reminded of the atmosphere of pubs in Tilbury and Grays in the 1970s and ’80s when I was a barman. Visiting seaman used to be in port for a number of days and were frequent visitors to the local pubs.

All this began to lose momentum in the 1980s as vessels had fewer crew and no longer spent enough time in the ports to afford their crew spare time to socialise outside the dock. Nowadays, most of pubs around the docks have sadly closed.

The apprentice: Kate Cameron

Apprenticeships for young people who worked on the river are an area close to my heart — both my children did apprenticeships; my daughter being the first ever female apprentice. Although they attended college, apprentices learnt most aspects of their craft from working afloat — this knowledge isn’t something that can be learnt in a classroom.

Jimmy Penn was interviewed by the museum in 1986. I knew Jimmy, and hearing his voice again takes me back years. Here he speaks about apprenticeships.

Becoming qualified to work on the river is no small task. An apprentice is bound to his master (who must be a freeman, a licensed waterman or lighterman) for up to seven years. Historically, this would be their father. ‘Indenture papers’ that the apprentices were given at the beginning were divided in two, with the apprentice and the master each given half. Both parts would be put together once the apprentice achieved his ‘freedom’. This was known as ‘being bound’.

Love of the river: Susan Winterbourne

My dad, George Roberts, was a lighterman (someone who transferred goods between ships and quays) on the Thames from the age of 15 in 1951, until the end of his career in the mid-1980s. He loved working on the river; the camaraderie, loyalty and trust he shared with his crew on-board the tugs that he worked on will always be fondly remembered. This feeling is echoed in the words of these lightermen in the Museum of London’s collection.

Bargemaster and lighterman Edwin Hunt, recorded in 1987.

Lighterman Jeffrey Greenwood, recorded in 1986.

I felt quite overwhelmed to hear such honest and detailed memories shared by these men. My dad was apprenticed by one of his neighbours where he lived in Rotherhithe. I chose Jeffrey’s story to share because he highlights how neighbours helped neighbours along the riverside. How grateful I am that James Taylor kindly offered to be my dad’s master whilst he served his apprenticeship. Without his help, my dad would never have been able to become a lighterman and have the enjoyable working life that he had for over 30 years!

I am so happy to know that these precious memories will be kept for future generations. I feel immensely proud knowing that my dad played such a big part in the transportation of goods along the River Thames. Hearing the interviews has made me more appreciative of the hard work and, sometimes, difficult conditions that he and others faced.

Listen to some of the volunteer researchers talk about their experiences of the sounds of the docks.

London: Port City, which ended in May 2022, was delivered by the Museum of London in partnership with the Port of London Authority (PLA). PLA also provided access to resources, photography and film footage, together with information and support. Images and film are copyright of PLA, unless otherwise stated.

The volunteer research included here was part of the Listening to London project at the Museum of London, supported by The Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund – delivered by the Museums Association.