We're always growing our collections by adding new objects, like this beautiful wedding dress from 1925. But it came with a puzzle: has it changed colour from white to blue in the last 93 years? Fashion detective Beatrice Behlen is on the case.

Earlier this year we acquired a somewhat unusual wedding dress worn in 1925 and donated by the family of the bride, via her granddaughter Caroline. Unsurprisingly, wedding dresses are the type of object most offered to the Dress & Textile collection. Sadly we get far fewer offers of wedding suits, wedding saris, or other types of wedding outfits. Don’t get me wrong, we love wedding dresses, but we already have quite a large collection and cannot accept all gowns that are offered to us. We look at condition, storage requirements and how much related material – accessories, photos, possibly even film – have survived that will help us tell the story of the dress and the bride when it is displayed. Sometimes it is still very difficult to decide. I hate saying no to anything offered so kindly, it is one of the most unpleasant parts of my job.

So why did we take this dress? In her initial email, Caroline, mentioned that her grandmother’s gown was ‘of blue silk, with vibrant red and orange painted flowers on the skirt’. This seemed unusual for a wedding dress, although painted silks appear to have been in vogue during the interwar years. We have another mid-blue painted dress from the 1920s, and an evening gown from 1932 designed and painted by the sister of the wearer. The Courtauld's collection includes a dress and shawl made of painted silk produced by the London Footprints workshop, which, admittedly, look rather different from the dress offered to the museum.

Of course, wedding dresses have not always been white and are of course not always white now. We already own a blue wedding dress, but that was worn in 1885 when not wearing white was less unusual. We have a wedding dress made of a gold sari given to the bride’s family from 1931 and another gold creation worn in 1937 by a bride who refused to wear white as the groom was not prepared to put on a morning suit. From the 1920s, the decade of the offered gown, we hold wedding dresses in colours including oyster, pink and lilac. Gold and pastel shades are quite different from a deep blue, however, and some of the colourful wedding dresses might not have been worn in church, which was the main thing that puzzled me.

This is not the actual mystery, though. I get to that in a moment, but first a bit about the bride and groom. The dress was worn by Ethel Florence Silvina Jarman, born 1905 in Pimlico, just north of the Thames, the only child of Robert Lewis Jarman, a decorator, and his wife Emily Frances Neale. Some time before 1911, the family moved south of the river to Battersea. In 1923, Emily died and Ethel who was just 18 took on her mother’s housekeeping duties.

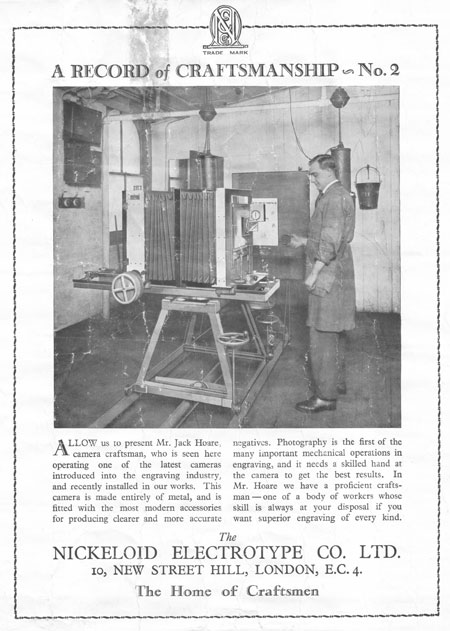

Ethel’s husband-to-be, Harold Victor ‘Jack’ Hoare was born in 1900 on the Isle of Dogs. His father Jacob worked for ‘His Master’s Voice’ (HMV), one of the labels of the Gramophone Company, where he was electroplating the master discs used to produce phonograph records. By 1918, the Hoare family had moved to Wandsworth right next to Battersea. Jack followed his father, becoming a process engraver, producing printing plates using a large camera. He even appeared in an advertisement for his company!

By the early 1920s Ethel lived in Shelgate Road and Jack in Chivalry Road, practically around the corner from each other. They might have seen each other in the street, or they might have met at ‘church socials’. St Mark’s Church on Battersea Rise, where Ethel and Jack married on 27 June 1925, was only a few minutes walk from either of their homes.

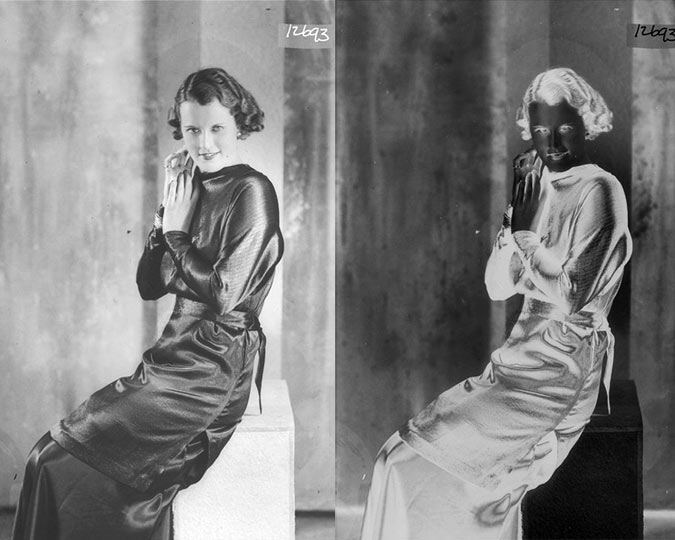

Ethel and Jack Hoare, 1925

This is where we get to the mystery. Seeing the dress myself emphasised the vibrancy of the blue colour, the iridescence of the gold accents and also the brightness of the red, yellow and green paint used for the flowers, which are almost encrusted onto the dress. Our conservator Emily wondered whether crushed glass was involved.

Caroline also showed me two photographs of Ethel and Jack. The family assumed they were taking on the wedding day, as one of them has the date handwritten on the back. Sure enough, Ethel is wearing the dress, but - and it’s a big but - it looks white and the flowers appear black and monochrome, rather than shaded. Now, in some respects it made much more sense for Ethel to have worn a white dress, but why is it blue now, what is going on?

Before I had seen the photos, I thought the blue dress might not have been put on for the actual wedding ceremony, but as a ‘going-away’ outfit afterwards. That is still a possibility but does not explain why the dress appears white. For a while, I was even entertaining the thought that Ethel liked the dress so much that she acquired two versions. Speaking of which, the family does not think Ethel had artistic aspirations and are quite sure she did not do the painting herself. There is of course the possibility that someone put the wrong date on the photo, but Caroline assured me that her ‘aunt and cousin (who my grandmother used to live with) have always said the blue dress was the wedding dress’. Ethel had also kept it all these years, which suggests that it was of importance to her.

The hem of the wedding dress

Caroline thought of something else. She was wondering whether the dress could have been dyed after the wedding, an idea I was very taken with. Judging from the trade directories covering the King’s Road, which I studied in great detail at one point, dry-cleaners often offered dyeing services at least until the early 1970s. The thread visible on the hem of the garment could support this hypothesis.

It seems an odd colour to use, maybe it did not take the dye in the same way as the main fabric. But what about the flowers? If they had been black before, they would have had to be overpainted after the dyeing. Or maybe it is just the low quality of the black and white print that makes the flowers appear to be monochrome? Zooming right in on a digital reproduction of the print suggests the flowers had been shaded all along.

Perhaps some of you remember the white and gold or black and blue dress phenomenon that occupied so much internet space in 2015? Ours is obviously a different situation, as all of us who looked at the actual dress saw it as blue and everyone perceived the dress in the wedding photo as white. I was hoping that photographing the dress might reveal some strange reaction to lighting, but it did nothing of the sort.

Richard, who photographed the dress, had another idea: ‘It may have been that the original photo was taken with a blue filter, which would filter out the blue and make it appear lighter. Doing the same thing in Photoshop gave a similar result when I applied a blue filter to the modern photo.’

This theory takes us back to the white/gold, black/blue dress. It seems that the colour of the lighting affected how it was perceived: yellow-coloured lighting made most people see the dress as black and blue, whereas under lighting with a blue ‘bias’, the dress was more likely to be seen as white and gold.

I wish I could tell you that we worked it all out, but I can’t. Currently, I would put my money on a combination of sunlight, film stock and perhaps also film processing that together produced this effect. If you have any ideas, or know about the film used in the 1920s for photography, please get in touch.

You will want to know about Ethel and Jack. After they married, the couple stayed with Ethel’s father in the family home at 20 Shelgate Street, where the photo was taken, raising one son and one daughter. Jack died in 1965 and Ethel moved, but only a few streets south, where she lived until her death in 1982.

Love fashion? Subscribe to our fashion newsletter to read more stories from our collections, and find out about upcoming events and exhibitions.