Our Roman Dead exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands was built around a newly found relic of Roman London: a stone sarcophagus, burial place of someone rich and important from Roman London. Curator Jackie Keily writes about the discovery and display of this rare artefact.

What inspires an exhibition at the Museum of London? Sometimes, we want to show off a specific part of our collections, like the Cheapside Hoard or the pioneering photography of Christina Broom. Sometimes, we are offered a brilliant partnership: Tunnel: The Archaeology of Crossrail or The Crime Museum Uncovered. These ideas go through various internal committees and external evaluations before getting the final go-ahead. But sometimes, we find something so exciting that we simply have to put it on display- and quickly.

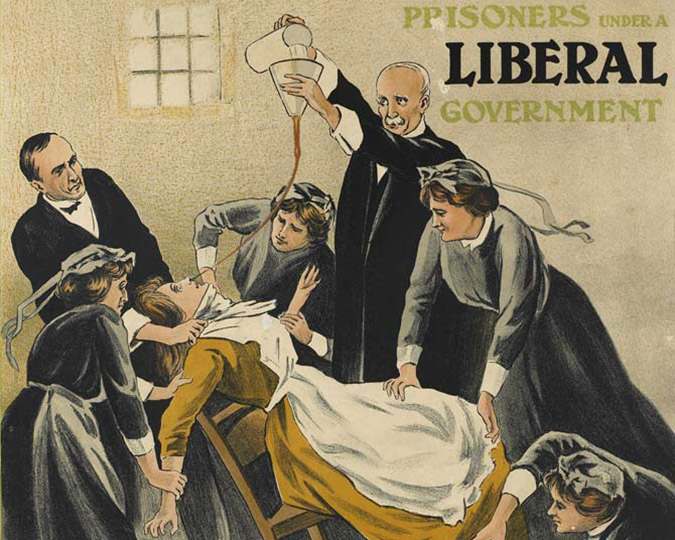

The sarcophagus on site at Harper Road, Southwark

© Pre-Construct Archaeology

In June 2017 we received a phone call from the archaeologists at Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd. They had found a Roman stone sarcophagus on a site they were excavating on Harper Road in Southwark. As Senior Curator in charge of the Roman collections at the Museum of London, I became very, very excited.

Roman Londoners were either cremated or buried in coffins. Of the latter, most were buried in wooden coffins or shrouds. However, a small number of very wealthy Roman Londoners were buried in stone sarcophaghi, stone coffins with lids. The stone sarcophagus often contained a lead coffin, with the body inside that. Only three sarcophaghi have been excavated in London in the last 30 years and the last one was in 2006. It really is the stuff that dreams are made of for a curator!

We hurried to the site and under strict secrecy were allowed to see what had been excavated. The lid and one side of the sarcophagus were visible, the remainder still under excavation. The archaeologists were getting towards the end of their time on the site and we immediately began discussions about what we could do to display the sarcophagus as soon as possible.

While this was going on, I and my co-curators, Meriel Jeater and Dr Rebecca Redfern, started work on the content of the exhibition that would surround the sarcophagus. We didn’t know exactly what the sarcophagus contained, or if it would even be possible to display it, due to its fractured condition and weight. We started building an exhibition to put the sarcophagus in context, in Roman Londinium and the theme of death in the Roman period.

Opening the sarcophagus

Pre-Construct Archaeology excavate human remains from the Southwark sarcophagus

© Pre-Construct Archaeology

It was evident on our first visit that the lid was cracked and had been moved at some point in the past, so speculation was that the coffin had been robbed. However as the lid was still in place, covering most of the interior of the coffin (which was filled with earth), it was hard to know how much of the contents of the sarcophagus had been disturbed. It was decided to remove the sarcophagus, contents and lid to the museum’s premises at Mortimer Wheeler House, where the contents could be carefully excavated under controlled conditions.

A couple of weeks after we had made our original visit to the site, the sarcophagus was free of the soil and was lifted by a crane onto a lorry and taken to Mortimer Wheeler House. Once there, the PCA osteoarchaeologist, James Young Langthorne, painstakingly excavated the contents: the near complete skeleton of an adult woman, some bones of an infant, and two tantalising remains of jewellery.

Jasper intaglio from the Southwark sarcophagus

One is a tiny fragment of gold sheet, possibly from a necklace or earring. The other is a stone intaglio, a small oval of jasper, which would be set into a ring and is carved with a figure of a satyr, a follower of Bacchus. The excavation of the interior also made clear the extent of the cracks in the sarcophagus base.

We knew due to its condition that display might be difficult and so commissioned specialist stone conservators, Taylor Pearce, to assess it and conserve it. We also had to think of the logistics of displaying such a massive, heavy object: when lifted off site the combined weight of the base and lid was some 2.5 tonnes.

We wanted to display the sarcophagus at the Museum of London Docklands. The museum, however, is housed in an early 19th century warehouse, which is a Grade II listed building. Specialists were called in to assess the floor loading and exactly where we could display the sarcophagus and how we could get it into the building.

Creating the Roman Dead exhibition

Installing the sarcophagus via crane at the Museum of London Docklands

We had less than seven months before the proposed opening date, in May 2018. Usually, we would borrow objects from other museums to display in an exhibition, but the short turnaround meant we wouldn't have time to source external loans. Luckily we know how fantastic, varied and rich the Museum of London's collections are in the material culture of Roman London.

We began by looking through published reports of Roman cemetery excavations in London, then located the original objects in our Archaeological Archive. The exhibition has given us a fabulous opportunity to display objects and stories that have lain in our stores for years, but it has also allowed us to showcase objects already on display in our permanent Roman Gallery.

The curators of Roman Dead analyse the contents of a cremation vessel

For example, a large glass bottle, which normally sits on a shelf in our Roman kitchen display, was actually a cremation vessel. We have displayed it in Roman Dead with the cremated remains found inside, and the small ceramic bowl that was used as its lid. Other glass, ceramic and stone cremation vessels usually feature in the permanent gallery in a display case of cremation vessels. We have been able to separate the vessels out and give them a starring role. Rebecca was also able to undertake detailed examination of the cremated remains in these vessels, something that had not been done before.

The results of this work are also on display: we created captions with skeleton diagrams to indicate which bones are present or absent and how much of the individual’s cremated remains were placed in the cremation vessels. We know that sometimes as little as 20% of the cremated individual was placed in a vessel. We don’t know why this is – perhaps the size of the pot or glass jar being used dictated how much of the ash and bone was placed inside it, or perhaps some people’s remains were separated out into a number of different vessels and buried in different places. The fact is that we do not know the answer and this is the same with many aspects of death in Roman London.

In the exhibition, we admit to not knowing the answers. As with so much of the past, we are constantly discovering new information, and research is continually pushing the boundaries of our knowledge. This means that sometimes interpretations and ‘facts’ do change and we wanted to acknowledge this in Roman Dead.

In addition to displaying the woman from the Harper Road sarcophagus and the objects found with her, we have displayed ten other skeletons of Roman Londoners. In each case we have displayed them lying as they were found, accompanied by the objects that they were buried with. Some of these objects are normally on display in the Roman Gallery. So, again, the exhibition has given us the opportunity to re-unite these individuals with their grave goods.

Creating this exhibition has been an amazing project for not just the curators, but for the whole project team. It is a testament to the richness of just one small area of our amazing collections – bringing together objects from our Archaeological Archive and our core museum collections. We are incredibly grateful to all those who worked so hard to bring it together in such a short time and hope that you get to visit before it closes on 28 October 2018.

Love Roman Dead? Want to get updates about the city's past straight to your inbox? Sign up for our free Archaeology newsletter.

Roman Dead closed on 29 October 2018.